Miscellaneous

A Tale of Two Paatis

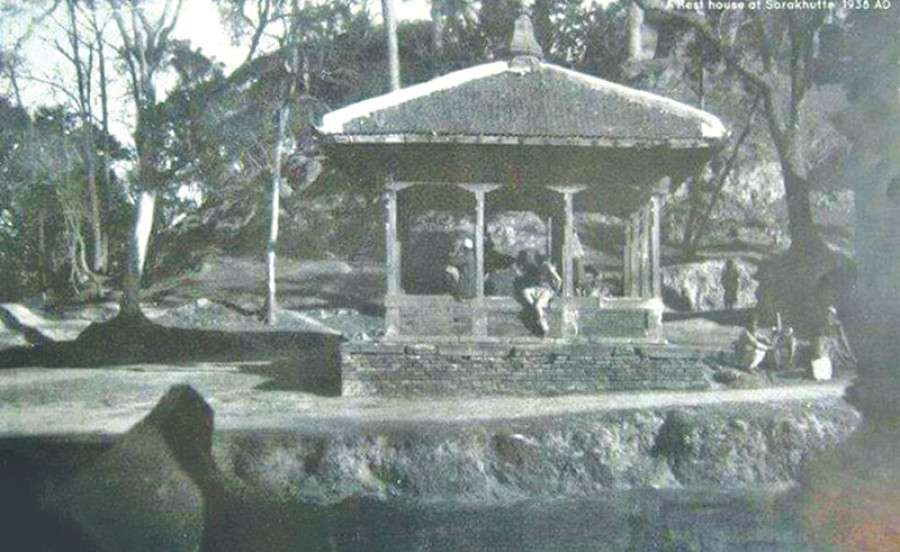

The Sorakhutte Paati, according to historical records, was built by the children of Kazi Damodar Pande,” recounts Rahendra Pradhan, 58, a local resident of Thamel.

Astha Joshi

The Sorakhutte Paati, according to historical records, was built by the children of Kazi Damodar Pande,” recounts Rahendra Pradhan, 58, a local resident of Thamel.

Until a few years ago, for commuters en route to Naya Bazaar and beyond, the Sorakhutte Paati, standing precariously with a sense of abandonment at the edge of the busy junction, was a familiar sight.

The paati, however, was demolished as part of the road expansion drive in January 2015, in spite of vocal opposition from local communities. At the time, the Prime Minister’s Office had directed the Department of Road to relocate the rest house to a nearby location, in coordination with the Department of Archaeology, retaining its original aesthetics and building materials. Yet, two years down the line, the paati has not just failed to rise again, government officials have no clear answer as to where the salvaged building material is, or if the rest house will ever see the light of day again.

In the last few years, there has been a constant outcry from heritage experts, conservationists, activists, and locals about the destruction of heritage sites and rebuilding that does not take into account conservation guidelines.

Increasing urban sprawl has led to traffic congestion in the city and road expansion projects in areas consisting of heritage structures, considered a solution to manage traffic congestions, has only added to the difficulties to their preservation.

Kathmandu Valley’s culture is unique not just because of its architecture but because these spaces are living and dynamic. People interact with heritage spaces on a daily basis and cultural and social practices revolve around these interactions. So, a loss of a tangible heritage doesn’t just affect the physical structure or its aesthetics but also directly affects the intangible heritage of Kathmandu. Each and every structure, regardless of their shape and size, also has a history attached to it. Paatis—or Phalchas in Nepal Bhasa—are just one of the many physical structures, which despite taking a small area in the city landscape are an important narrative of the socio-economic history of Kathmandu valley.

For instance, Sorakhutte, meaning “16 wooden pillars or legs”, derives its very name from the 207-year-old paati that once marked the outer fringes of Kathmandu proper. Historically, the paati was an important marker on the trans-Himalayan Kathmandu-Nuwakot-Kerung trading route that led north into Tibet. However, it was most popular as a resting spot for traders from towns in Nuwakot and Trishuli, who came to Kathmandu to trade their wares.

“When I was a child, traders from Nuwakot resting at Sorakhutte with their huge pack of goods was a frequent sight. These traders would stay overnight at the paati and would head out in the morning to the main city. They even lit firewood there to cook their dinners,” reminisced Pradhan.

“We only had a small road in that time. The downhill road that leads towards Naya Bazaar didn’t exist then. It was lined with thick cover of trees…more like a jungle,” he remembers.

When this historic paati was demolished, the Department of Road had also announced Rs 3.4 million for its relocation. As per reports the said amount was supposed to be given to the Department of Archaeology who would oversee its relocation 50m southeast to its original location. But even after the roads were expanded, Sorakhutte’s relocation remained in limbo, especially after the earthquake.

According to Dev Kumar Tamang, Division Chief of the Division Road Office, Kathmandu-2, Department of Roads (DoR), the DoR had not received the required funds which led to delays in the call for tender. The recent local elections have led to further confusions over the project.

Tamang states: “The responsibility of maintaining the inner roads now falls under the jurisdiction of Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC). Our budget for the paati might also be cancelled. We will know for sure by Shrawan.” These changes have further created uncertainty about the Sorakhutte’s relocation project.

The spokesperson for KMC, Gyanendra Karki, stated the newly elected Mayor of Kathmandu, Bidya Sundar Shakya’s plans also includes addressing the relocation of Sorakhutte Paati. However, queries about where the sixteen post and other building materials salvaged from Sorakhutte Paati are stored was still not clear with KMC officials and neither with the Department of Roads, who in turn directed the queries to locals.

“We have them. The wood and bricks are at the premises of the old age home at Sorakhutte,” informed Krishna Kumar Dhakal, President of the Nepal Barishtha Nagarik Samaj (Nepal Elderly Society). The elderly home lies opposite to the Sorakhutte Police Station, on part of the 20 ropani area that Bhotu Pande (subordinate commander during Rana Bahadur Shah ’s reign), donated. Dhakal who has been a leading voice for heritage preservation in Sorakhutte area initiated the meeting called between the Department of Roads and locals whereby the DoR agreed to fund the relocation of the paati. “We have minutes of the meeting from Poush 11, 2071 too,” he says.

Despite the frequent changes of plans, with designs that have been revised up to three times, Dhakal is hopeful that Sorakhutte Pati will be relocated to its proposed new location at the corner of Lekhnath Sadak. “We met the officials in a meeting recently, and I am hopeful as they have finally called for tender,” he states. He was unaware of the recent confusions that have arisen about the project as KMC is in charge of the inner roads of Kathmandu.

Meanwhile, in Bungamati, another Sorakhutte Paati is also fighting for its existence. This paati lies on the downhill road that leads towards Chafal, Bungamati. Although they have similar name, the Bungamati Sorakhutte is made of 16 brick columns, with a Jhingati (Newar brick tiles) tiled roof. The Department of Road as part of its road expansion project have plans to demolish this paati as well. But unlike the Sorakhutte Paati in Kathmandu, there has been no talk about its relocation. The paati is presumed to be more than 100 years old, but given the lack of documentation, the exact date cannot be verified.

“The paati was used by traders from the South of the country on their way to Kathmandu. Ritual offerings by the local guthi during Yenya Purni were also conducted at the paati, but the practice has been discontinued for many years,” states local architect Anil Tuladhar.

With the aim of protecting it, Tuladhar along with a local youth group are in the process of drawing proposals to restore Sorakhutte, Bungamati with the intentions of adaptive re-use. The designs and interventions will be based on present needs and will acknowledge conservation practices. Adaptive designs, keeping in mind local needs, hopes to keep intact the heritage and traditional form of the structure and most importantly, ensure continuity of cultural practices. Efforts are also being directed by the local youth group towards reviving the guthi culture in Bungamati which has been on the wane in recent years.

Tuladhar states, “We can ensure that the heritage of Sorakhutte, Bungmati is preserved if we can alter the road’s alignment or track. But this can only happen if and only the DoR agrees to it. We also need community engagement to raise urgency of the situation. For this, we are actively working towards increasing youth participation in community activities, including the guthis.”

Protection of heritage structures, especially structures like paatis and private houses has been a challenge even before the earthquake. The April 2015 earthquake further increased their vulnerability. Adding to the growing challenge towards preserving heritage is the discontinuation of cultural practices that are related to these tangible heritages. Disengagement of local people and community with organisations poses a threat to the continuation of traditional, cultural and social practices of Kathmandu Valley. In time, memories of the heritage slowly fade away from the collective experience and narrative until it becomes non-existent in the memories of the future generations.

This again brings us back to the question about whose heritage these are? Who is responsible for preserving it? Why we need to care in the first place.

Joshi is a Kathmandu-based writer who writes about culture and heritage

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu