Miscellaneous

Youth is wasted on the young

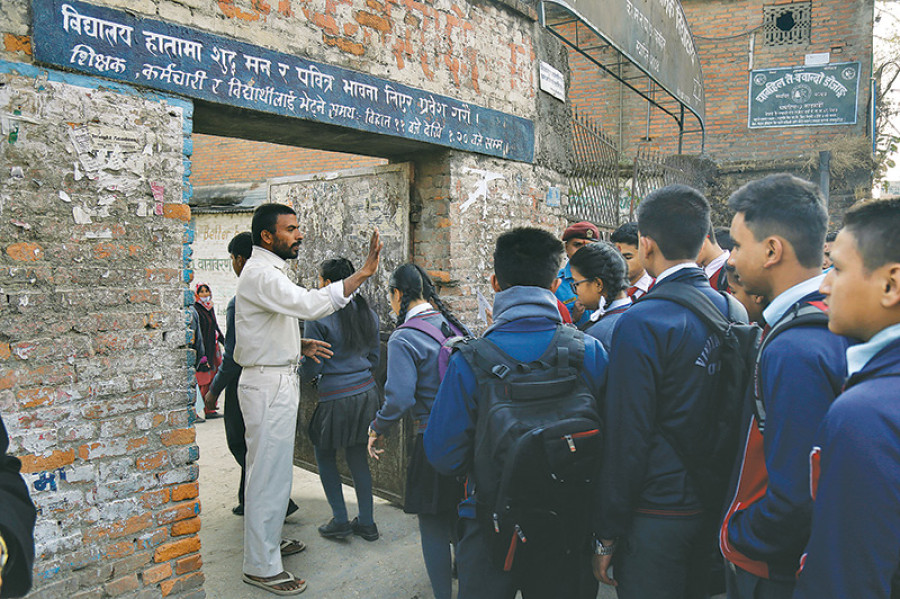

The end of school is sweet not only because most students will have been sixteen—for a while, the young hearts may feel like a tethered horse set loose—but also because it is the threshold into adulthood which marks involvement in family decision-making and recognition by the state as citizen.

Mohan Guragain

The end of school is sweet not only because most students will have been sixteen—for a while, the young hearts may feel like a tethered horse set loose—but also because it is the threshold into adulthood which marks involvement in family decision-making and recognition by the state as citizen.

But sixteen could also be sour, especially when more responsibility falls onto the young shoulders. To many, it may be an exciting mix of sweet and sour—an age of both opportunities and challenges.

Youth and SLC have been interlinked for a while now. The recently concluded central test is now termed the School Education Examination (SEE), but still continues to remain a week of cramming and reproducing for an important assessment. Two years ago, the School Leaving Certificate meant massive failures and usually entailed heavy “cheating” to avoid them. SEE doesn’t fail a candidate directly. However, it does so through circumspection, by assigning poor grades, which mean denial of admission into the so-called good colleges of the land.

For the fortunate ones, gadgets, bikes and good courses await. For those already indebted, 12 becomes the final grade of study. After 18, their surest bet is a difficult job in an unknown foreign land.

To many village girls, finishing school—often dimly—signals the departure from the parental home. Not on a journey to the city for college but to be married off to a stranger arranged for by her poor and uneducated parents.

A couple I know, who operate a store together, have been saving for months as their tenth class graduate will now need a decent mobile phone—his first, as children don’t carry them to school. The three months before the SEE results are out, it is time for the new ‘graduates’ to mingle with the wider society, emerging for good from their narrow school community.

Times are fast changing. Twenty years ago, passing the SLC could provide one access to far off towns where humble youths from villages could travel on buses, watch TV and talk on the phone, renting a cheap room together with a mate from another village or district. They would have nobody to check if they gambled or studied since guardians of only a very few had the means and the conscience to visit them or help them settle there in the first place.

Passing subjects was more out of “luck” than hard work. Nonetheless, study was valued as some of the students went on to become teachers or government officials.

Now studying has little meaning for many. It costs money, takes one’s precious time and leaves many astray when they end up not worthy of the rare well-paying jobs. What makes sense for many is venturing abroad early on, earning enough to buy or build a house, getting married and going back to the Gulf or Malaysia again while the baby grows up under the care of the mother and grandparents.

Society has grown so materialistic that people—young and old—are judged for their cash or wealth, not for their character, knowledge, education and integrity. Money, it seems, washes away all of one’s sins; riches bring prestige to anyone no matter how crooked they once were.

In this mindset, it has become really challenging to teach the budding generation any lasting values.

Despite their tremendous power and potential, the youth are vulnerable to their whims and fancies or emotions. They are not free from the shared weaknesses of the common folk. The budding generation may be aware of the problems plaguing the society but feel helpless about resolving them. More worryingly, youths cannot break free of grand national designs—from, historically, participating in wars to Nepal’s present predicament of having to rely on foreign employment to sustain both household and national economies.

But just check, almost everyone seems to have a cure for the country’s ills of unemployment and lack of productivity. The trick is to correct the “dirty” politics, which is possible only by ridding the parties of their old, visionless leaders. For that, youths have to be brought to the forefront of politics, which is easier said than done.

Many had believed that a new constitution would usher in a new era in Nepal. They may be right but our ethnic tension threatens to abort the process of transformation. This danger stems from the bitter realisation that very few seem to be acquainted with the constitutional framework.

Two major cases are the ignorance among most politicians about the shape of the local federal units the new charter envisages to carve out; and the laws that have thrown many new political forces out of the local level election process. Did the MPs pass the laws without knowing what they provision?

Thus, when the country’s leaders and intellectuals seem to have a poor sense of what is happening around them, the youth cannot be expected to make measured moves.

Bewildered, those with the means will continue to leave the country in droves for study, work or residence abroad. In the dearth of pride in citizenship, many can choose to spend their productive years in foreign lands, whether or not they are able to contribute significantly to their home country in the process.

Come July, half a million youths in their late teens will be at a loss for what to study for a successful future. They will find more commercially interested academic entrepreneurs than philanthropic thinkers to show them the career options.

If some are wasted out of their free will, it is an exception rather than the rule. But our policy at large is not geared to provide proper orientation to this generation of hope. We, unfortunately, continue to fail to harness the power of our youth.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu