Miscellaneous

Beggars or choosers

Over the years, there has been a growing body of literature on why Nepal has failed to develop—Nepal kina banena.

Akhilesh Upadhyay

Over the years, there has been a growing body of literature on why Nepal has failed to develop—Nepal kina banena. This vital debate has been approached through various disciplines and perspectives, and has explored various related issues including the politics of foreign aid, the deep-seated Hindu caste system, fatalism and patriarchy, and lately, extreme political instability, policy corruption, the inevitable dependence and nervousness that comes with landlockedness, and the ebbs and flows in the giant theatre of geopolitics.

Indeed, we in the media and those who appear in our Opinion pages have tried to bring a multiplicity of views on these deeply troubling issues to public view. But there are no easy solutions. We have perhaps explored the problems far better than we have been able to offer solutions. But the fact is that one cannot uphold a single school of thought as providing the correct analysis and offer a simple diagnosis. Clearly, there are many inter-related issues that need to be tackled.

This is why I found a new book on development aid by leading lights from a range of backgrounds fascinating. For those of us forever troubled by Nepal’s underdevelopment, Aid, Technology and Development offers unique insights into aid and development and how an underdeveloped poor country becomes dependent on international aid while remaining unable to develop.

Edited by Dipak Gyawali (a hydroelectric power engineer who once became Minister of Water Resources in the Nepali government), Michael Thompson (a teenage soldier in the Malaysian ‘emergency’ who subsequently became an anthropology-cum-policy analyst), Marco Verweij (professor of political science at Jacobs University in Bremen, Germany), the book, as the subtitle suggests, offers the lessons from Nepal to the world.

The book is divided in three parts and has 13 chapters. The first three chapters offer a conceptual framework of development post World War Two, and seven subsequent chapters consist of in-depth case studies of development projects. The final two chapters offer broad perspectives based on the Nepal experience and ideas on how we can kick the habit of our dependence of foreign aid. The Afterword minces no words, in both rhetoric and substance, on what went wrong and what can be done so that we don’t repeat past mistakes.

These last two chapters, intriguingly, are authored or co-authored by Prakash Chandra Lohani and Dipak Gyawali, who have themselves held various top-level policy positions in Nepal over the decades. One wonders why they were unable to apply their insights while they were in a position to do so. Perhaps wisdom arrives only after one steps away from active duties.

The early chapters of the book, grouped under the rubric Dharma of Development, explain the history of foreign aid and how aid-receiving poor countries like ours fall into dependency on the international aid industry. If six decades of foreign aid has at best had mixed results, the book asks, do we really need foreign aid, and if we do, for how long?

The book tries to provide answers through seven case studies, asking why the vast majority of development projects go wrong while only a few perform well.

This brings us to the heart of the book: What is development? Is it a mere economic phenomenon, as we are made to believe by the market pundits, or is far more complex than that?

“Development has long been seen as very much an economic process…Increasingly, however, it has become evident that it is economic only in its consequences; it is something else—entitlements, democratisation, social capital—that makes development possible.”

From the launch of development assistance in the late 1940s to the early 1980s, the notion held sway that ‘development’ could be measured by the annual growth of per capita national income, that ‘such growth could take off in developing countries if significant amounts of capital were transferred from the coffers of rich states to those of poor ones,’ observes a contributor. Then came the era of ‘structural adjustment’ or the ‘Washington Consensus.’

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a lack of development was mainly viewed as caused by a series of market ‘imperfection’ in poor countries. In the 2000s, the emphasis was on ‘good governance’ and ‘aid effectiveness.’ The book argues that there is scant evidence that the aid effectiveness paradigm of the post-Washington Consensus era has not been effective either. In recent decades, countries like China, India, Indonesia and Brazil have had most success in fighting poverty and they mostly did so without foreign aid.

Beyond the Age of Aid, the concluding two chapters, offers how we can get out of the trappings of foreign aid. “Nepal is strewn with highly expensive development failures that have lined the pockets of Western consultants and companies, as well as less than honest domestic decision makers,” according to the three book editors. They offer, among others, examples of ‘the infamous’ Arun III dam and other large hydro projects, often pushed by the World Bank and other aid donors; and the “ill-fated privatisation of Bara forest, foisted upon local communities by a Finnish logging company and the Finnish International Development Agency in the 1980s.”

But there have been some positive interventions as well. The Bhatte Danda Milkway, proposed by Nepali experts and supported by the European Union, enabled the transport of milk produced in the villages to urban Kathmandu. It also ended up finding new markets in Kathmandu for local produce—an unforeseen development.

The successful scaling-up of bio gas with the help of the Dutch government is another positive example. But by far the biggest and most noteworthy contribution was the establishment of internationally-acclaimed community forest user groups through grants from Australia and the United Kingdom.

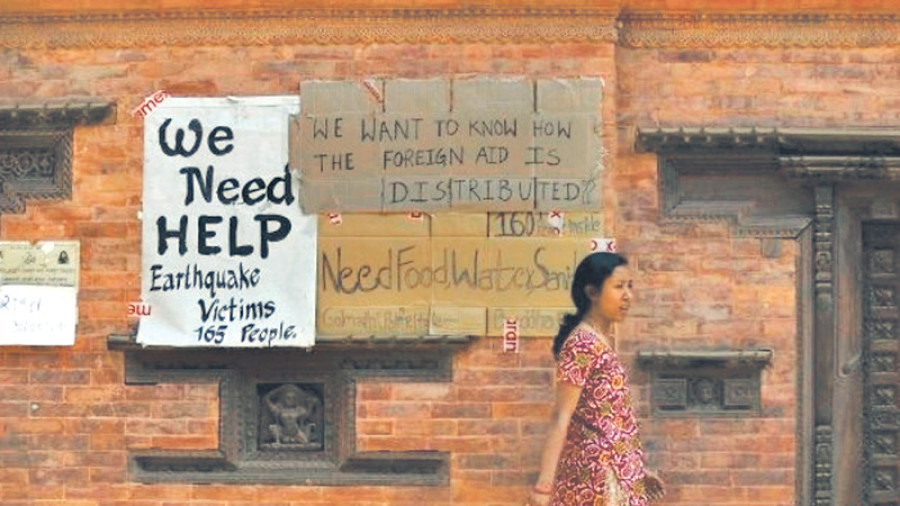

But aid priorities are still misplaced. For instance, while climate change has now become the new buzz word for most aid agencies, from a Nepali perspective a plethora of other issues appear far more pressing. These include daily electricity blackouts, insufficient water supply and poor sanitation, severe air pollution in Kathmandu, the needs of reconciliation after a deadly civil conflict, struggle against corruption and reconstruction of livelihoods from the destructive earthquakes of April 2015. The book documents all this.

In many respects, Aid offers a one-window peep into what’s gone wrong for us, as well as lessons on how we can help shape foreign aid so that it is time bound and prioritised according to domestic needs and experience and knowledge.

Given its depth of argument and range of case studies, I would suggest that the book be made compulsory reading for all development practitioners and academics, foreign and domestic, who are working on Nepal.

11.42°C Kathmandu

11.42°C Kathmandu