Karnali Province

Jajarkot quake-displaced still stuck in temporary shelters

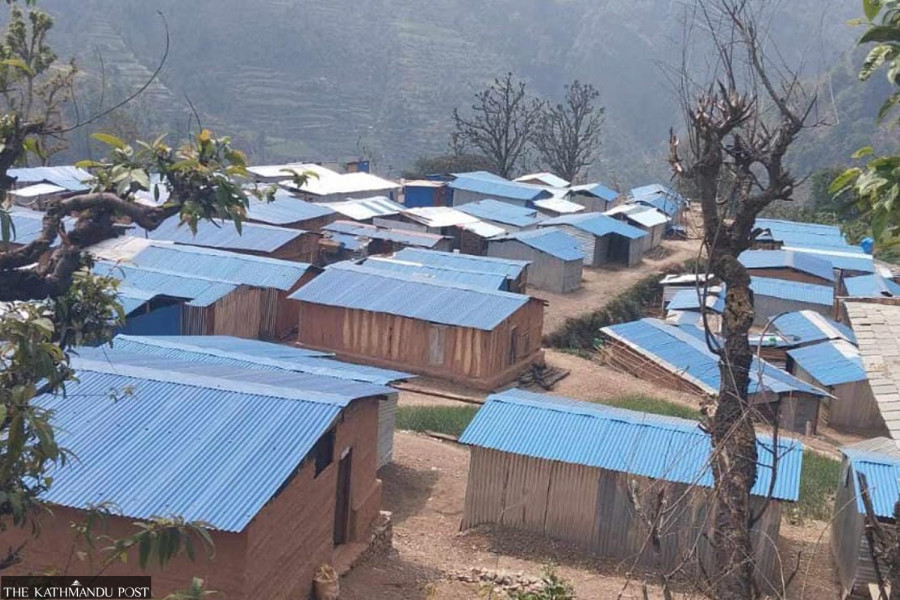

Twenty-two months since the disaster, thousands of survivors have yet to receive reconstruction aid as damage assessment drags on.

Krishna Prasad Gautam

For the past 22 months, Laxman Rawat has been living with his family of eight in a flimsy tin-and-plastic shelter in ward 1 of Rawatgaun of Bheri Municipality in Jajarkot district. Every evening, he worries less about aftershocks but more about what his family will eat the next day. “If the government had built us a permanent shelter, I could have gone to India for work and supported my family,” he said. He earns a meagre wage by loading and unloading goods from vehicles at Rimna Bazar. “Instead, we have wasted nearly two years just waiting. If they had told us to build on our own, we would have borrowed and done it already.”

Laxman’s neighbour Purna Bahadur Rawat carries even heavier suffering and grief. He lost two young sons when their home collapsed during the quake measuring 6.4 on the Richter scale. Since then, six members of his family have been crammed into a single leaking room of a temporary hut. “When it rains, water drips everywhere. During the sunny day the tin roof turns the room into an oven,” he said. “How can a family live, eat, and sleep in such a space? It is unbearable,” he lamented.

The devastating earthquake of November 3, 2023, with its epicentre in Ramidanda of Barekot Rural Municipality, killed 154 people and damaged around 76,000 houses across Jajarkot and Rukum West. Yet a year and a half later, the detailed damage assessment (DDA) report—crucial for determining grants for rebuilding—remains incomplete.

Officials acknowledge the delay. “The assessment began only in February this year, nearly 15 months after the quake,” said Samir Gautam, an administrative officer at the District Administration Office in Jajarkot. “Although fieldwork is over, classification of the damage is still pending, which means the final report is not ready. Without that, reconstruction funds cannot be released.”

Under the existing legal provisions, local ward offices must sign agreements with beneficiaries and forward them to the local disaster management committees, which then recommend them to the district disaster committee. Only after the verification the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority disburses funds. “We can send budgets to the local units only after verification is complete,” Gautam explained.

Preliminary surveys had recorded about 48,000 damaged houses in Jajarkot, but later figures revised the beneficiary count to around 43,000. So far, 43,086 households have received the first tranche of reconstruction aid and 36,000 the second. Still, thousands remain in limbo, unable to start work until the DDA report is complete and grants finalised.

The government has promised Rs400,000 per family for rebuilding destroyed homes, Rs250,000 for retrofitting partially damaged houses, and Rs100,000 for minor repairs. But frustration is mounting among survivors who feel excluded. “Our names never appeared on the government website,” said Chakra Bahadur BK of ward 7 of Nalagad Municipality. “Families with multiple houses got their assessments done, while poor people like us, with homes cracked beyond repair, were left out,” BK vented his ire.

People’s representatives admit technical and procedural shortcomings while preparing the rosters of beneficiaries. “The authority conducted the assessment in its own way, leaving out many genuine victims,” said Prakash Gharti, mayor of Bheri Municipality.

The conditions inside the temporary shelters are dire. “We live under leaking roofs, with landslides threatening from above. When it rains, we cannot sleep at all. We stay awake all night, fearing the shelter will collapse,” said Surbir Lohar of Chiuri in ward 1 of Nalagad Municipality.

The delays have also driven away aid groups. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, some 25 organisations worked in Jajarkot, supporting relief, temporary housing, health and sanitation. Now, almost all have left. “They brought programmes on livelihood, education and drinking water, but without progress in reconstruction, they could not continue,” said Sahadev Basnet, Jajarkot chairman of the NGO Federation of Nepal. According to him, about Rs300 million worth of planned aid has already been withdrawn. “Nearly 300 locals had jobs through those organisations, but when the reconstruction stalled, they had no option but to leave.”

The memory of the disaster lingers. After the quake, an additional 63 people died in landslides, floods and cold-related illnesses across the district. Survivors complain the Rs25,000 paid in two tranches for temporary housing was insufficient. “That money barely covered tarpaulins and tin sheets,” said Laxman. “We need homes, not handouts.”

Thousands of earthquake-displaced families continue to live in temporary shelters or quake damaged houses due to the delay in reconstruction and rehabilitation of the victims. The quake victims are exposed to threats from landslides and floods during monsoon while they are left shivering under flimsy huts in winter.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu