Editorial

Monsoon maladies

The authorities need to prioritise efforts to fill the gaps within the health sector.

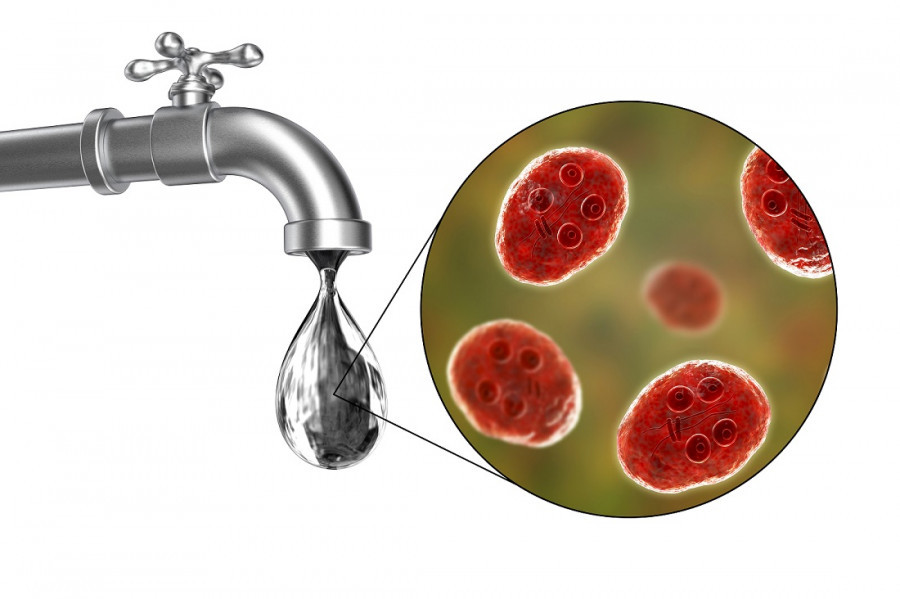

With the incessant rainfall the country has been witnessing in the past few weeks, the need to tackle Nepal’s issues during the monsoon has taken centre stage once again. Bountiful rainfall is a boon for an agro-based economy like ours. Ironically, despite the abundance of river bodies, farmers in Nepal and the entire sub-continent depend on the seasonal downpour to ensure a healthy harvest. This dependence is primarily rooted in our inability to tap the free-flowing resource and work it to our advantage. But the monsoon brings far more pressing concerns in the form of water-borne diseases that brutishly plague the region every year.

Nepal is highly vulnerable to water-borne and vector-borne diseases like diarrhoea, dysentery, typhoid, dengue and Kala-Azar. And with some of the illnesses sharing the same initial symptoms as Covid-19, people may wait for the virus to run its course instead of securing the necessary help, and be afflicted by something more sinister. In order to avert a looming health crisis amid the pandemic that still hasn’t shown any signs of slowing, the authorities need to prioritise efforts to fill the gaps within the health sector by ensuring that health posts are equipped with the required number of health professionals and medications.

It is a needless travesty that despite recurring health issues, the authorities are seen as incompetent and powerless in overcoming them. It is undeniable that the country would fare better in proactively approaching the problem than waiting for the case load to increase. Water-borne diseases have the highest morbidity and mortality rates among communicable diseases in Nepal. Yet, the maxim prevention is better than cure seems to evade the very conscience of the authorities. If the crux of the problem relates to manpower shortages once the epidemic has taken hold, we need to seek alternative ways to tackle the menace.

For instance, mobilising the workforce in raising awareness programmes could go a long way rather than pursuing the reactive methods of the past. There are several ways to prevent water- and vector-borne diseases; emphasis could perhaps be laid on sound environmental practices, flushing and discarding stool and cleaning the surroundings with the appropriate disinfectants, promoting good personal hygiene, taking food precautions, and above all, drinking treated water. More often than not, people take good hygienic practices for granted, and easily fall prey to the imminent health crisis.

With one set of elections out of the way and another fast approaching, there is a pressing need for the authorities to address underlying gaps in the health system. Perhaps for once, they should adopt unique plausible measures that have never been tried in Nepal but have the credibility to ensure success in tackling the issues at hand. And while we contemplate the application of preventive actions, emphasis must still be laid on providing the necessary health care to the scores that will, unfortunately, be affected this monsoon.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu