Interviews

South Asian countries have lost their ideological sovereignty

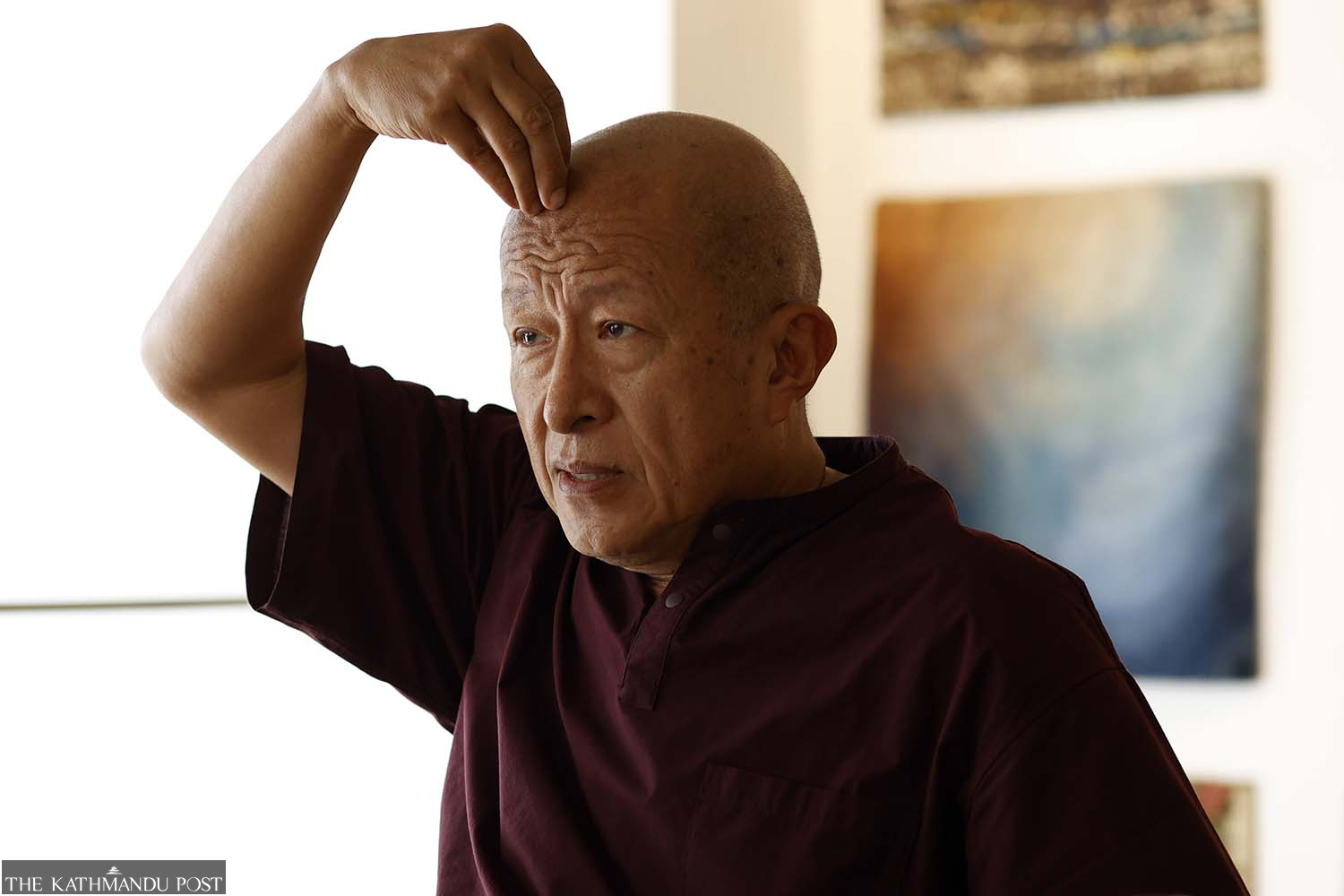

Bhutanese filmmaker Khyentse Norbu discusses why he works with non-actors, the changes he’s seen in Nepali society, and how beautiful shots can be bad for a movie.

Anish Ghimire

Lately, glitzy movie premieres and box office numbers have been grabbing headlines. But away from it all, Bhutanese filmmaker Khyentse Norbu is quietly making a new film in Nepal. The movie ‘Perfect God’ focuses on a Behrupiya (impressionist)—a traditional performer who paints as a deity and travels from village to village.

Today, the story of such an impressionist may seem outdated. But for Norbu, such a story carries a kind of romance and melancholy that refuses to fade.

Known for his spiritually rich films like ‘The Cup’ (1999), ‘Travellers and Magicians’ (2003), ‘Vara: A Blessing’ (2013), ‘Hema Hema: Sing Me a Song While I Wait’ (2017), and ‘Dakini’ (Looking for a Lady with Fangs and a Moustache) (2019), Norbu continues to explore the idea of identity, illusion and meaning.

In this conversation with the Post’s Anish Ghimire, the director—also a revered Buddhist teacher and writer—shares why he chose the story of Behrupiya for his new film and explains why beautifully shot films sometimes miss their point.

We’ve heard you’re quietly directing a new film in Nepal, ‘Perfect God’, with a local team. Is that true?

Yes, it’s still a work in progress. But yes, I’ve enjoyed working with many young Nepali talents. They’re incredibly creative, professional, and efficient. It’s been a great experience so far.

Is it too early to tell us what the film is about?

Not at all. I can tell you, though I’m not great at summarising. Summarising is an art, isn’t it?

This movie is about a Behrupiya. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of these travelling performers who paint themselves as gods and go from village to village.

There’s something deeply romantic, melancholic, and special about it. In today’s world, where we’re overwhelmed by Netflix, Amazon, and TikTok, we forget that just a hundred years ago, these performers were as exciting as any of that. That kind of culture, which existed worldwide, especially in India, has always intrigued me.

The story is about a Behrupiya’s struggle to survive in a world that no longer values his kind of performance.

Going back a little, ‘Dakini’ (2023) was shot in Nepal and screened for Nepali audiences. In a masterclass two years ago, you said, ‘I watched my film yesterday—the same one you all struggled to finish watching’. That wasn’t too long ago. How did the Nepali audience respond to the film?

Honestly, I was pleasantly surprised. Before ‘Dakini’—also known as ‘Looking for a Lady with Fangs and a Moustache’—I had made another film called ‘Hema Hema’. Both films tell relatively obscure stories. They’re not mainstream at all. I mean, who’s interested in such themes? One of them even explores what happens after death.

They’re not easy films—they can be abstract and hard to follow. So, I never expected many people to watch them. Maybe a few here and there. But the response, especially from the Nepali audience, was quite good. That made me happy.

You’ve been known to work with non-actors, especially in your early films. What draws you to that approach?

In the beginning, it wasn’t really a choice. It had nothing to do with comfort—I just didn’t have access to professional actors, so I worked with whoever was available.

But this time around, things were different. I finally had a proper cast of trained, experienced actors for ‘Perfect God’. In fact, this might be the first film where nearly everyone on screen is a professional.

Did that change your approach to directing?

Yes, absolutely. I didn’t have to do much. I mostly sat behind the monitor and let them do their work. It was great.

So you are more of a free-flowing director. You don’t really like to micromanage?

That’s partly true—mainly because I’m a little lazy, to be honest. But also because I trust my team. The actors are strong, the camera department is excellent, and the whole crew is good at what they do. If I micromanaged them, I’d only get in their way. So I let them be. And it worked out well.

You’re widely known as a Buddhist teacher. Is that why the soul of most of your stories tends to be spiritual?

Yes. You can’t escape it—even if you try. Sometimes I wish to make a film that has nothing to do with spiritual values, just to challenge myself. But I was born into Buddhism, raised in it, and have lived with it for a long time. So naturally, some kind of spiritual element always finds its way into the story.

But who knows, maybe one day I’ll end up directing something different, like ‘Wall Street’ part 3 or something.

What makes you want to try something different?

I believe it’s simply part of being human. We all want to share what’s in our minds. And there’s something thrilling about sharing an idea you consider unique, and then realising someone else understands it, even just a little. It’s like a small confirmation that your thoughts or creativity resonate with others. That’s always a special feeling.

What is the status of the long-term project to translate the 84,000 Buddhist teachings—originally written in Pali and Tibetan—into English? The goal was to complete it over a hundred years.

The project is going quite well—better than expected in some ways. But of course, there are still many challenges. In the past, we struggled to find qualified translators and skilled editors. Now, with the rise of AI, things are shifting.

A passage that might take a human translator two years to complete can now be processed by AI in just 30 seconds. That’s a massive change. But it also creates a new challenge; how do we verify and maintain the integrity of these translations?

Most of the information used by AI comes from databases created elsewhere, often from Western sources. This raises a serious concern. I believe countries in Asia—like Nepal, India, and Bhutan—have lost what I call ideological sovereignty.

Take Mustang, for example. If you want to learn about it, you’ll likely search on Google or Wikipedia. But the information you find there is probably written by someone living in San Diego. You, your friends, your children—you all read that and start accepting it as truth. Slowly, it becomes the dominant narrative, even though it wasn't authored by the people it’s about.

That’s worrying. I often joke with my Indian friends—yes, the CEO of Google might be Indian, but Indians still don’t control their own stories. They rely on platforms like Google and Wikipedia, which are based elsewhere. In that sense, I respect what China is doing. You may disagree with their version of the truth, but at least they tell their own story—and millions of people believe in it.

This is something we in South Asia need to think about seriously. I’ve noticed similar changes happening in places like Japan, which has become highly Americanised. Many young people there have little left of their original cultural mindset.

And I worry this could happen in Nepal too. In 10 or 20 years, Nepalis living abroad might not understand our sense of humour, our way of showing embarrassment, or the emotional layers that are so distinctively ours.

Anyway, due to AI, the project might be completed sooner than we had anticipated.

You first came to Nepal at the age of 13 and have been visiting regularly since then. How do you view the changes in Nepali society and the evolution of Nepali cinema?

Honestly, I don’t know much about Nepali cinema—at least I didn’t before. But now I’m beginning to understand it, and I think it’s amazing.

As for Nepali society, wow! Nepalis are incredibly resilient. Sometimes I feel like the whole world could collapse, and Nepal would still keep going.

I’ve seen it myself. There were years when the country had no stable government, but life carried on. I’ve visited Nepal many times, and I remember when people only had electricity for a few hours a day. Everyone was using generators. I still recall walking through Thamel; all you could hear was the constant hum of generators.

But people just adapted. That resilience is something very unique and something I admire.

Nepal also has a rich artistic legacy. Even mighty China recognised Nepali artisans as far back as the 13th century. Nepali artists wrote music and created beautiful works long before that, but the 13th century is one of the most famous mentions.

That spirit of creativity—of art and expression—is still deeply embedded in the Nepali identity. It’s in the DNA.

But I do think there’s something to be cautious about now. With the rise of platforms like Google, Wikipedia, and social media, there’s a risk of filling your mind with too much external content. Too much ‘processed’ creativity, if you will. And that might dull your originality.

This isn’t just about Nepal, it’s true for all of us. But I say this mainly because Nepal has such a long, proud creative history.

You say that beautiful shots might actually kill a film. What makes you say that? Aren’t beautiful visuals an important part of cinema?

Yes, of course. But my comment is quite broad—it’s not black and white. Beauty is subjective; it’s in the eye of the beholder. But I do think that sometimes, beautiful shots can become a distraction.

Let me put it this way: you can shoot a perfectly framed close-up of a lotus, a cup, or a drop of water on a leaf. It might be visually stunning. But if it doesn’t serve the story, it’s meaningless. That’s what I mean. A beautiful shot that doesn’t move the narrative forward—or deepen its emotion—can actually weaken the film.

You once said that Nepalis have original stories that should be told internationally. How long have you been observing Nepali stories, and how closely?

For a few years now. Nepal is overflowing with many stories, and I wouldn’t even know where to begin. Just walk into any souvenir shop, any statue store, and you’ll find contradictions, layers of history, myth, and struggle. You don’t need to dive deep into legends—every day Nepal has richness.

These stories are important, and I think they deserve to be explored and told more widely.

Your storytelling style in film is very distinct. How does one develop their own style and get comfortable with it?

That’s a difficult question. Let me give a slightly roundabout answer.

Think of it like this: I have something in my head that I want to express. But you, the listener, come from a completely different background. If I explain it exactly how I think, you might not understand. So I have to adjust my communication—find a shared language or a point of reference we both relate to. That’s where storytelling lives: balancing what the creator wants to say and what the audience can understand.

It’s very tempting to make a film purely for the audience, like a commercial blockbuster. You can just say, ‘Oh, you want this? Here, I’ll give it to you.’ That’s fine if your only goal is money. But I believe storytelling should be more than that.

There’s a term I like to use: ‘beautifully written bad scripts’. Take films like ‘RRR’, where one person kills a thousand others—it’s not real, but it’s entertaining. The structure is clear, the rhythm is tight, but the truth? Not always there.

In the past, I made personal films. I wasn’t thinking about the audience much. I just made what was in my head. A lot of people didn’t understand them. Many even fell asleep. One of my films was rejected by 38 festivals—probably just based on the first scene, which was a long, static wide shot. For me, that shot was fascinating. But others didn’t have the patience for it.

But that kind of filmmaking is even more challenging today as people’s attention spans are shorter than ever. How do you push through that?

I agree. But I still believe there are like-minded people out there—people who will get it. You just have to find them.

In today’s fast-paced world, with social media, constant information, fast food, and even global conflict, how can someone keep their mind clear? How do we remain free of mental fog and stay grounded?

That’s a difficult question, and I don’t have a concrete answer. But there’s something I was thinking about just this morning: the algorithm.

Algorithms now guide much of our lives—what we read, believe, and desire. And that can make us very confused. But maybe there’s a way to work with it.

You see, human minds are easily manipulated. Instead of being manipulated by just one source, let yourself be influenced by multiple sources. That way, at least, you become a more complex, thoughtful, and self-aware person.

Everything we consume—news, social media, culture—is created by humans. And human beings are always biased, even when they try not to be. So, if you want to learn about Pakistan, don’t rely only on Indian media. And if you want to learn about India, don’t only read Pakistani sources. Read both. The same goes for China, or the West—don’t just read Western reports on China, or Chinese reports on the West. Balance them.

Whether we like it or not, everything we read comes from a point of view. So the choice becomes: do you want to be loyal to just one biased perspective, or do you want to engage with many, and let them challenge each other?

For most of us, meditating in the mountains isn’t an option. So the next best thing is to stay aware, stay curious, and never assume you have the whole picture.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)