Columns

Gen Z revolt alone can’t transform Nepal

Gen Z seeking a new Nepal must grapple with structural economic and political realities.

Sisir Bhandari

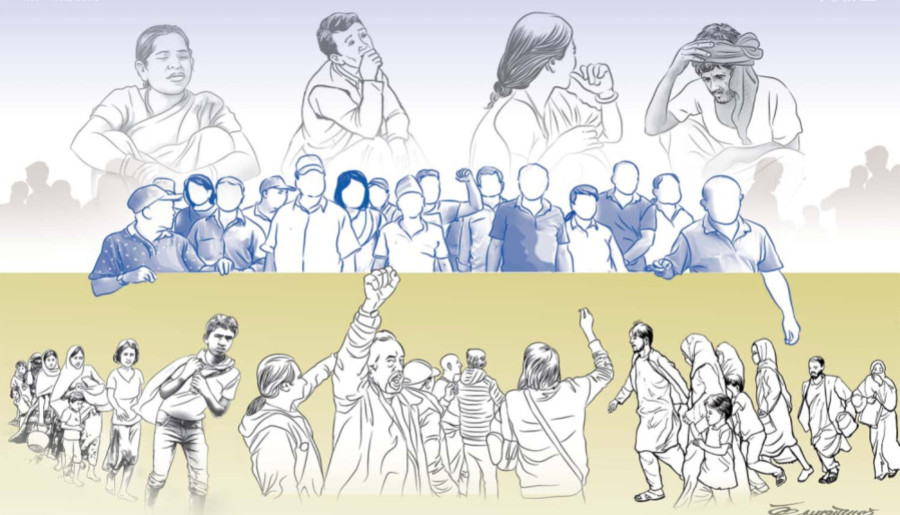

The September 8 and 9 revolution led by Gen Z shook Nepal. Fueled by blazing anger over the government’s failure to eradicate corruption and further intensified by a social media ban, protestors took to the streets in different parts of the country. The state responded with deadly force, claiming the lives of at least 75 people and injuring more than 2,300. What began as a spontaneous digital uprising led KP Sharma Oli to resign from his prime ministerial role, and eventually, the parliament was dissolved. After an agreement between the army, former chief justice Sushila Karki and the representative of the Gen Z protestors, an interim government assumed power with the mandate to hold new elections by March 2026.

The delirious psychology of this short-lived “Gen Z revolution” raises profound questions: Can such a momentous revolt truly remake a nation? What deeper obstacles lie beneath the country’s persistent underdevelopment? This article argues that Nepal’s transformation needs more than protests, governments and elections. It demands a long-term, multi-dimensional transformation of society, its culture and economy. The root problems of Nepal’s challenges run deep in its societal fabric, and overcoming them will likely be a “multi-generational project” that must be supported by education, empiricism and a shift towards a critical and productive mindset.

Anatomy of Nepali society

One can easily blame Nepal’s underdevelopment solely on corrupt politicians and bureaucratic elites. However, critics often overlook deeper sociological challenges that shape the character of Nepali society. Anthropologist Dor Bahadur Bista, in his seminal work Fatalism and Development (1991), described a pervasive fatalism in Nepali society that limits and often discourages initiative and accountability. The observation was that many Nepalis accept suffering, inequality and poor governance as fate beyond human control. Such fatalistic beliefs weaken demands for reform, as people assume that nothing can change, and corruption and misrule go unchallenged, eroding productivity and progress. Even today, fatalism often leads citizens to tolerate inept governance rather than call for change.

Patriarchal and patron-client norms further complicate Nepal’s path to reform. Nepali society remains patriarchal not just in gender roles but also in its broader social hierarchy and loyalty structures. There is a strong tendency to prioritise family, kin, or local community interests above common or national interests. Leaders and citizens alike often remain loyal to their own patrons or kin, reinforcing patron-client networks throughout politics and business. Nepotism, cronyism and favouritism have become a religion, devaluing merit and normalising corruption. This causes political parties and institutions to function more as patronage clubs than issue-driven entities.

Culturally, Nepali society also exhibits obedience to hierarchy and a resistance to open discourse. Children are encouraged to respect authority and discouraged from questioning those in power. In workplaces, classrooms, or politics, a culture of silence often dominates over debate. This cultural conservatism means new ideas and critiques are often dismissed. As a matter of fact, after the recent protests, many party cadres steeped in these hierarchical norms tried to delegitimise the Gen Z movement. They began spreading conspiracy theories claiming that “foreign forces” were behind it. Such attitudes reflect a deeper clash between a globally exposed youth and a traditionalist older generation.

Gen Z activists, despite their access to information and progressive outlook, remain a part of a society where fatalism, patronage and hierarchy are deeply ingrained. Without addressing these sociocultural foundations, any political revolution risks being short-lived with limited impact.

Limited innovation and economic challenges

The aforementioned societal constraints have direct consequences for Nepal’s economic development and environment for innovation. The country’s economy has experienced only modest growth over the past two decades, with real GDP growth averaging around 4 percent annually, which is considered sluggish for large economic gains, as seen in Bangladesh and India. We can partly attribute this to the lack of innovation in domestic industries. For instance, being part of an open trade regime and in the absence of domestic innovation and comparative advantage, one becomes import-dependent.

The lack of an innovation-driven growth engine is also evident in global indices. Nepal was ranked 107th out of 139 countries in the Global Innovation Index 2025, placing 9th among 10 countries in South Asia. This poor ranking highlights Nepal’s limited progress in leveraging creativity, technology and productivity to drive its economy. Aside from some small-scale advances, such as community forestry and hydropower projects, Nepal has a limited number of home-grown manufacturing, technology, or agriculture innovations. Traditional enterprises dominate the private sector, where research and development spending by both the private sector and the government is negligible. A society constrained by fatalism and nepotism is unlikely to generate opportunities in scale, scientific breakthroughs, or gains in comparative advantage trade.

If not innovation, what has sustained Nepal’s economy? Remittances from migrant labour have been a lifeline for its finances. With limited opportunities at home, millions of working-age Nepalis have sought employment abroad, from the Gulf and Malaysia to India and beyond. Today, approximately one-fifth of the country’s population consists of migrant workers. These workers send home billions of dollars each year, which supports household incomes and the national balance of payments. Nepal received around $11 billion in remittances in 2023, which in recent years has equated to over a quarter of its GDP. The World Bank noted that Nepal was the world’s third-largest recipient of remittances as a share of GDP in 2019. This influx of cash, earned by Nepalis sweating in construction sites, factories and domestic work overseas, has enabled the country to import consumer goods and fuel economic activity despite weak domestic production. Thus, Nepal has become a consumer society with limited innovation, leaving its economy vulnerable to external shocks and conflicts.

Beyond remittances, Nepal’s other potential growth drivers remain underdeveloped or uncertain. There is potential for hydropower and tourism, which have often become victims of political instability. Large-scale manufacturing and high-tech industries are almost non-existent or lack competitiveness in regional markets.

Gen Z activists seeking a new Nepal must grapple with these structural economic realities. Any new leadership will face the same fundamental questions: How to create jobs at home for the vast unemployed population? How to move beyond import dependency and low-skill labour exports towards a more productive, services-based economy? These are long-term challenges that a sudden change of government alone cannot resolve.

In essence, the Gen Z uprising was a necessary shock to the system, but it is not, by itself, sufficient to transform the system. To avoid becoming merely a footnote in history, this youth movement must evolve into a sustained force that steadily advocates for more comprehensive reforms. It should realise that no single charismatic leader or quick fix will magically solve Nepal’s problems. The interim government and upcoming elections present a window of opportunity for Gen Z to influence the agenda. However, achieving real results will require patience, pragmatism and national effort from all parties.

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu