Columns

Act of conscience

Few in Pakistan organise themselves to protest against injustices.

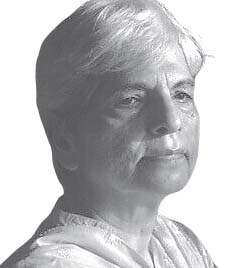

Zubeida Mustafa

“If the pain has often been unbearable and the revelations shocking to all of us, it is because they indeed bring us the beginnings of a common understanding of what happened and a steady restoration of the nation’s humanity. The TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] that is guiding us on this journey is the TRC of all of us”—Nelson Mandela

Coming from a leader who spent 27 years of his life in prison on Robben Island crushing stones, these words show sagacity and astuteness. They must be reflected on. Mandela, who led South Africa out of the black hole of apartheid, allowed his people to protest but prevented a bloodbath when the transition took place. Protest was the silent voice of the people’s conscience. Hence, it had to be peaceful. If it turned violent, then it was not protest but vendetta. And that can never be justified.

Mandela was a shrewd statesman. He understood how his people had been brutalised by their White Boer colonisers and how bitter they felt. Hence he convened a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to listen to the outpourings of people who had suffered all kinds of indignities and injustice. What was the outcome? Nothing in practical terms but it brought closure to the South Africans, enabling them to come to terms with their past and work for their future.

Protest is said to be a potent force for political change. Yet few in Pakistan organise themselves to protest against the injustices meted out to them in abundance by the powers that be. Why this apathy? We are such a divided society where what is a bane for one is a boon for the other. People protest if they are directly affected. They turn a blind eye to the injustice that affects the weak and underprivileged classes, who lack the capacity to mobilise themselves and create awareness about the issue that is at the root of the problem.

But that does not mean we do not have protesters. To be a protester, one must be an activist and have a social conscience. These qualities are inborn, and it is difficult to inculcate them in a person who inherently lacks empathy and a sense of justice.

The women’s movement in Pakistan would not have considerably changed the status of women in the country had we not had women like Anis Haroon and Sheema Kermani and many others who lined sidewalks with banners in their hands. They created original slogans and managed to evoke passion and protest among like-minded men and women. The younger generation went further and the Aurat March was born.

Fearing resistance from civil society, autocratic governments have clamped down on protesters and in fact banned organisations that have organised protests, such as student bodies and labour unions. That had an impact on the culture of protesting and made the youth apolitical.

Mercifully, we still have men of conscience who have not given up. Take Naeem Sadiq, who spends a lot of time doing research to unearth facts and gets them from the horse’s mouth so that he can convey the magnitude of the injustice being meted out to the powerless—be they sanitary workers or bodyguards employed by banks and other organisations. Another demand he supports is a ban on guns.

Only recently I discovered another protester of a unique kind. He is Abdul Hamid Dagia, who has been protesting against the injustices done to Karachi since 2015. Eighty years of age, he has chalked up 1,440 one-man protests, which is a record of sorts. A chartered accountant by profession, Dagia held coveted jobs at the Karachi Electric Supply Corporation and the stock exchange until the mid-1990s, when he gave up a stable career that he found dissatisfying because of the abundance of wealth surrounding him and the opportunities it offered for financial misappropriation. It was the inegalitarianism of the situation, leading to injustice, that touched his conscience.

What makes him unique is that he protests single-handedly. Thrice a week, he is out on the road—a quiet, aged figure holding his placard announcing the injustice that is bothering him. His causes are Karachi-centric. One banner says, ‘Lawaris Karachi’ (ownerless Karachi).

Another is ‘Darakhton kee katai bund karo’ (stop cutting trees), which earned him the wrath of the KMC’s tree cutters, who allegedly attacked him. Yet another says, ‘Sindh budget dugna, Karachi ka hissa kahan?’

“Do people join you in your protest?” I asked him. He says that an odd passerby or two does come and stand with him for a moment or so. “Once a judge noticed me. He stopped his car and joined me in solidarity,” Dagia sahib remarks. A judge with a conscience. We need more of them.

-Dawn (Pakistan)/ANN

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu