Columns

Where to find other funds?

Nepali universities (except for Kathmandu University) have relied overwhelmingly on state funds.

Pratyoush Onta

In 2007, the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha wrote: “The Indian university has relied too heavily on subsidies and handouts from the state.” The situation in Nepal is pretty similar. Over the years of their existence, Nepali universities (except for Kathmandu University) have relied overwhelmingly on state funds for their expenses, both infrastructural and operational ones. Fees charged from students in public universities, except for some MPhil/PhD programmes, have been nominal. By diversifying its sources of funding, Guha added, “The university reduces its dependence on a single source of patronage, while also engaging with (and making itself relevant to) a wider swathe of society.” If Nepali universities want to diversify their sources of funding, what else could they do more robustly?

In terms of other sources of funding, one strategy, already in use to a certain extent, is to look for research funding mainly outside of Nepal. Increasingly, this kind of funding is being realised in collaborative research projects jointly executed by faculty members from Nepali universities and those based in universities abroad. Other sources of funding to explore (within Nepal or from Nepalis world over) would include contributions from alumni, the private sector and private individuals. Let us discuss the latter three today.

Alumni contributions

Funding from alumni is one obvious source that has not been cultivated by Nepal’s universities. Given the large number of its graduates, for Tribhuvan University (TU), established 1959, this is a big possibility that remains largely untapped. Since TU was the only university in Nepal for many decades, almost every household in Nepal has one or more TU graduates. However, no one seems to know their exact number (the same is true of the number of people like me who attended a TU college for a year plus, but do not have a formal degree from TU). One former vice-chancellor suggested in 2015 that there were at least 1 million TU graduates. Let us assume that that number is correct for the purpose of this discussion. If, on average, each graduate contributed only Rs5,000 per year, TU would end up with a fund of Rs5 billion that could be used to cover its costs. That is more than half of what TU got from the government during a recent fiscal year.

In the real world, not every graduate of TU could or would contribute Rs5,000 every year. But some would be able to contribute a bit more (say Rs25,000). Those who are financially well off would be able to contribute a lot more (say Rs100,000). While no one can predict what such annual contributions might add up to before such a funding drive is actually attempted, theoretically it can total more than Rs5 billion per year.

For the universities founded in the 1990s—Kathmandu University (KU), Purbanchal University and Pokhara University—raising funds from their alumni should also be a possibility, although on a smaller scale since the total size of their alumni is much smaller compared to that of TU. In its website, KU states that more than 30,000 individuals have graduated from its seven schools. Since I could not find any further information on the subject, I do not know if KU’s alumni, including its graduates from its medical, engineering and management schools, have started contributing to their university. If they have, it would be interesting to know what the total volume of such contributions amount to annually. If such a tradition of giving does not exist, the younger universities should invent and operate fund raising drives among their alumni.

Regarding how to do this, Nepali universities will need to learn a thing or two from the American universities that have well-established systems of collecting small donations from their alumni. These universities keep reminding their alumni to give back to their alma maters. In the previous century, alumni of American universities like me would get regular letters asking for donations for amounts as little as $10. Nowadays, such reminders come mostly by email with full instructions on how such donations can be made online. With individuals being able to transfer money digitally these days, Nepali universities can similarly resort to smart apps to collect funds from their alumni. Regarding alumni who can give bigger donations, in person conversations would be important.

Private sector contributions

Nepal’s private sector has grown multiple times in the last 30 plus years. While the number of successful private companies with very high annual profits is rather small, I would still think that some would be willing to donate regularly to Nepal’s universities. These could come in the form of contributions to the core funds or support for particular research projects. Alternatively, they could come in the form of an endowed professorial chair on a theme that is close to their business remit. For instance, a bank could endow a professorial chair in macroeconomics or a sociology chair in migration studies (given the remittances that pass through such banks these days).

To incentivise such contributions from the Nepali corporations or multinationals active in Nepal, the system of tax deductions regarding them would have to be friendlier. Currently, if a corporate entity gives more than Rs100,000 to a non-profit (for example, a university) during a single fiscal year, the excess amount is taxed at a rate of 25 percent. That is no incentive for corporations to donate to universities.

Individual contributions

Recently it was learnt that an endowment fund celebrating the memory of famous lawyer and intellectual, the late Ganesh Raj Sharma, had been set up at KU by his daughter Dr Mridu Sharma. The size of this endowment is Rs4 million. Its interest income will provide a need-based scholarship to a woman student enrolled in KU’s five-year joint Bachelor of Economics and Bachelor of Law programme. Apparently, KU has an established mechanism to set up such endowments for amounts over Rs2 million. According to information given in an online brochure on KU’s website, more than 40 such endowment funds have already been established for specific purposes, with the total amount exceeding Rs300 million.

I have heard that such endowments have also been set up by private individuals at TU in the past. It is possible that some such set-ups have already been made in Nepal’s other younger universities. More research on this kind of financial arrangement at Nepal’s universities would be really useful.

But setting up endowments is not the only mechanism through which private individuals can donate to universities. These institutions can also do with many small donations from the families of their students, members of their staff and other well-wishers from all walks of life. The mechanism described above to collect small donations from their alumni could be used by these universities to collect similar small donations from various individuals.

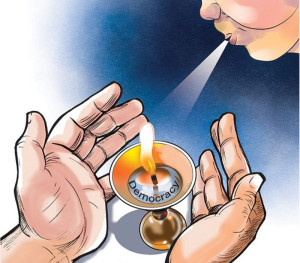

Hence, the funding challenge to our universities is this: Will they continue to rely overwhelmingly on the annual grants from the state or will they make serious efforts to diversify their sources of funding? Realising multiple robust sources of funding would be absolutely necessary if our universities are to revitalise their everyday educational functions and long-term governance autonomy.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu