Columns

The realities of provincial budgets

Provincial budgets reflect broader challenges in the federal planning and budgeting system.

Khim Lal Devkota

The budgets for the fiscal year 2025-26 presented by all three tiers of government have drawn attention from the public, stakeholders and political actors. The federal budget, in particular, sparked serious controversy in the House of Representatives. Lawmakers from both ruling and opposition parties criticised the government for politicising budget allocations.

While the allocation of federal funds to the constituencies of prime ministers, ministers and influential leaders is not new, it has worsened in recent years. Budget distribution is now regarded as more politicised and less restrained. Reports indicate that some ministers and their secretariats are directly interfering in the ‘Line Ministry Budget Information System’, undermining transparency and accountability. Budget allocations among ministries have become erratic, and development projects are now being allocated in the names of members of Parliament—both from the House of Representatives and, more recently, the National Assembly. This practice raises serious concerns, as it compromises the checks and balances essential in a democratic system and discourages critical oversight by lawmakers.

When lawmakers become beneficiaries of development funds, they lose the ability to hold the government accountable. Consequently, only representatives with underfunded constituencies raise concerns. Project distribution often ignores key factors like population, geographic diversity and development needs, prioritising political influence and favouritism. The National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission and the National Planning Commission have failed to enforce their mandates, rendering them weak and ineffective. This flawed practice, rooted in federal budget-making, is now spreading to provincial governments, undermining transparency and accountability at all levels.

Similarly, provincial budget allocations have also come under criticism. Chief ministers and provincial ministers face accusations of diverting a disproportionate share of the provincial budget to their own electoral constituencies. In many cases, project allocations are reportedly determined through political bargaining between ruling and opposition parties, which reduces budget distribution to a tool for power-sharing rather than addressing real developmental needs. As a result, the principle of participatory planning—essential for inclusive and transparent budget formulation—has been largely sidelined.

Instead, projects endorsed or pushed by MPs have gained prominence, regardless of their alignment with broader provincial development priorities. Although official guidelines state that projects should be selected from the Project Bank, the system remains largely dysfunctional. Many budgeted projects are not even listed in the Bank, as confirmed by officials of the planning commission. Furthermore, although the federal government has pledged not to fund projects below a threshold of Rs30 million, most development ministries—including the Ministry of Urban Development—have violated this provision. This compromises the integrity of the planning and budgeting process at all levels of government.

Unless corrective actions ensure transparency, discipline and fairness in project selection and budget allocation, public trust in the federal system will keep declining. This erosion of trust poses serious risks to the future of federal democracy. While recent debates have centred on distributional disputes, a deeper analysis of provincial budget sources reveals crucial structural trends.

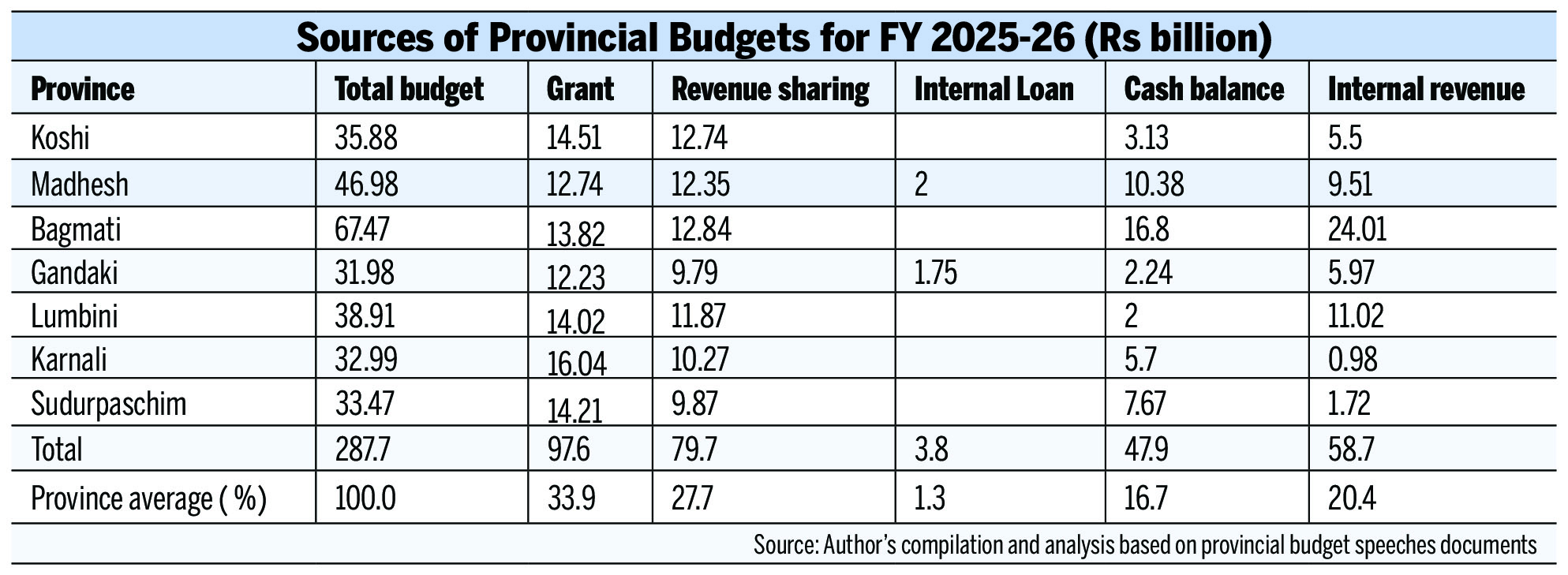

The provinces immediately presented their first budgets in the FY 2017-18, after the formation of provincial governments in February 2018. At that time, the total combined budget of all seven provinces amounted to only Rs7.14 billion. Given the political uncertainty surrounding the elections, particularly in the context of the Madhesh movement, the federal government provided each province with an equalisation grant of 1.02 billion rupees, which served as the basis for their initial budgets. The first full budgets were introduced in FY 2018-19, with a total volume of Rs208 billion across all seven provinces. In the following year, provincial budgets increased to Rs259 billion. From this baseline, provinces have presented eight annual budgets, including the FY 2025-26, which stands at Rs287 billion—an increase of Rs10 billion compared to the previous year.

A significant portion of the provincial budgets is sourced from federal transfers. In the 2025-26 budget, 33.92 percent of the total provincial budget—approximately Rs97.56 billion—comprises federal grants. Among these, the equalisation grant makes up the largest share at 62.18 percent, followed by conditional grants at 31.11 percent, special grants at 3.35 percent and matching grants at 3.36 percent. The share of grants in provincial budgets has gradually declined in recent years. In 2019-20, federal transfers accounted for 45.22 percent of provincial budgets; in 2020-21, they made up 37.80 percent. The figure of 33.92 percent indicates a positive trend towards reducing dependency on federal grants, suggesting that provinces are slowly building their fiscal capacities.

Provinces like Madhesh, Karnali and Sudurpaschim—which lag in human development and other areas—should have been brought into the mainstream through special grants. However, this has not happened. The entire grant distribution system needs a serious review, because of the unscientific nature of the equalisation grant formula and the controversies surrounding conditional grants.

Revenue sharing is the second-largest source of provincial budget revenue, contributing 27.71 percent to the overall budget. Under the Intergovernmental Fiscal Arrangement Act of 2017, the subnational units receive 15 percent of the value-added tax (VAT) and excise duty on domestic production. In fiscal year 2019-20, revenue sharing accounted for 25 percent of provincial budgets, which dropped slightly to 23 percent in 2020-21. The amount received through revenue sharing depends entirely on the VAT volume and national excise duties.

Provinces have significantly improved their internal revenue generation, with tax revenue now accounting for 20.41 percent of the total provincial budget, up from 11.24 percent in 2019-20. In FY 2025-26, internal revenue is projected to reach nearly Rs59 billion. Bagmati leads with Rs24 billion, while Karnali lags behind with just Rs980 million.

A substantial share of provincial budgets comes from unspent funds or “cash balance” (Alya), which makes up 16.66 percent of the FY 2025-26 budget, totalling Rs47.9 billion. Bagmati has the highest cash balance at Rs16.8 billion, while Lumbini has the lowest at Rs2 billion. This growing reliance on leftover funds signals weak budget execution and planning. The Ministry of Finance warns that using unspent grants as revenue distorts accountability and reduces development impact. The cash balance share has varied in recent years, indicating persistent fiscal inefficiencies.

Meanwhile, internal borrowing remains minimal in FY 2025-26 provincial budgets, accounting for just 1.30 percent of the total. Only Madhesh and Gandaki included internal loan projections—Rs2 billion and Rs1.75 billion respectively—but neither of them actually borrowed. Similar patterns were seen in Koshi in 2020-21. The Ministry of Finance has criticised provinces for projecting loans without federal consultation, warning that such practices inflate budgets and mislead the public.

The realities of provincial budgets reflect broader challenges in the federal planning and budgeting system. Politicisation, weak planning and poor implementation undermine trust and effectiveness across all levels of government. Reform is urgently needed not only in provincial but also in federal budgeting. Coalition leaders must take this seriously and promote inclusive consultations among political, governmental, and civil society sectors. Institutions like the Fiscal and Planning Commissions should lead these efforts. Addressing these issues ensures transparent, accountable and equitable budgeting for a functioning federal democracy.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu