Columns

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure

As the virus disrupts economies further, there may be opportunities for some to drive out competition.

Paban Raj Pandey

If the Covid-19 pandemic has thrown your life into disarray, you are definitely not alone. Most have been affected—not just individuals, but also businesses and governments. Globally, surgeries have been postponed and companies have shut down operations, not to mention governments have been struggling to cope with hospital capacity that is stretched thin. The medical community is yet to fully wrap its head around the true nature of the virus, let alone know where it is headed. In this time of uncertainty, companies are drawing down bank credit lines and raising cash when they can. When it is all said and done, those with healthy balance sheets with sound cash cushions probably stand to pick up assets on sale.

Already, countries are tightening the rules to protect their companies from unwanted solicitation. India just introduced new foreign direct investment rules designed to scrutinise investments from companies based in neighbouring countries. The probable objective is to stave off takeover attempts by Chinese companies. Within a couple of months between January and March, the Sensex crashed over 39 percent. As of Wednesday, it is still down 25 percent from its high. Valuation multiples have come down, which is likely to attract suitors. Australia, Germany, France, Italy and Spain have made similar moves. Australia has said it will now review all proposed foreign investments into the country. The goal is to prevent a fire sale of distressed corporate assets.

Cycle analysis key determinant of investment

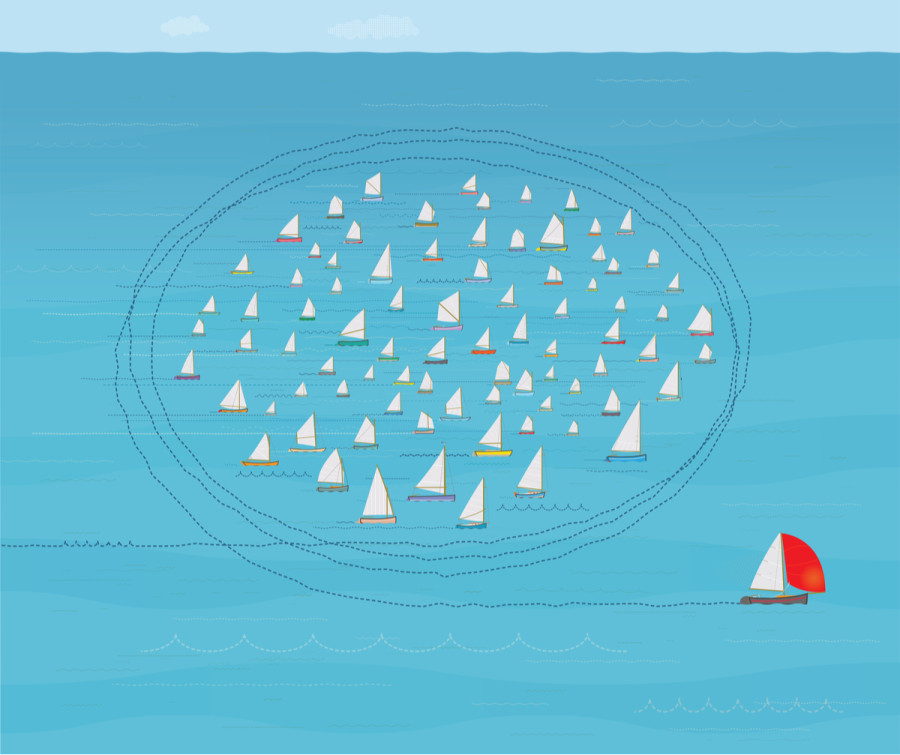

The coronavirus is all set to change the competitive landscape in all kinds of industries and sectors—both within national boundaries and globally. Some companies will emerge stronger relative to their peers, while several others may not even survive the crisis. In business, cycle analysis plays an important role. No two cycles are alike. But at the same time, there is truth to the phrase ‘history doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes’. It is the ability to aggressively expand when sentiment is the bleakest and lighten up when it is the brightest is what separates the wheat from the chaff. Cycle analysis helps companies identify when to build cash/pay off debt and when to take on leverage.

In more ways than one, the global economic expansion that just ended was getting long in the tooth. After the financial crisis of 2007-2008, major central banks flooded the system with liquidity. This surely served as an economic backstop, but also denied a real shakeout from happening, thereby opening the door to more risk-taking. Debt, which is what led to that crisis in the first place, kept growing. Stock markets soared, but growth was sub-par in major economies. Then came the US-China trade war that took a heavy toll on business confidence. All in all, the global economy was already fragile before the virus hit, waiting for a catalyst to tip it over. Arguably, the virus accomplished just that.

Nepal, as reliant as it is on tourism and remittances, cannot remain unscathed. This can create opportunities for healthy companies to weaken, even drive out, competition. It is not quite comparable, but what is currently transpiring in the oil market serves as an example. In the past, OPEC called the shots. The emergence of Russia and the current leading producer US has changed that. The price of Brent crude collapsed nearly 80 percent from its January high before rebounding. In April, OPEC+, made up of OPEC and non-OPEC countries including Russia, reached a deal to cut output by 9.7 million barrels/day in May and June, but demand destruction is much higher. A cynic may say the lukewarm cut is by design. At current prices, many US shale producers are likely to go bust. Saudi Arabia and Russia will cherish that.

Take the junk bond market of the eighties; the US suffered two recessions in the first three years. There had been two in the seventies. Then, in the early eighties, interest rates and inflation peaked. The economy began to grow, and junk bonds developed a new appeal. ‘Junk bond king’ Michael Milken helped popularise these bonds to finance hostile takeovers of companies, as the acquirer could raise serious capital with little or no assets. The insanity came to a full stop by the end of the eighties as defaults soared. Timing-wise, these companies were right to want to aggressively expand, but the financing vehicle they chose left much to be desired. There is good leverage and there is bad leverage.

Desperate times call for desperate measures. When governments fall on hard times, they do things that end up creating opportunities for the private sector. In Russia, the collapse of the former Soviet Union led to large-scale privatisation of state-owned assets under Boris Yeltsin in the early to mid-nineties. It was a fire sale. Massive amounts of wealth, most notably in oil and gas, went to just a few oligarchs with political connections. The UK experienced a recession in the early eighties. Margaret Thatcher came into power in 1979. By the time she left in 1990, more than 40 state-owned businesses were privatised, including British Telecom, British Airways, British Petroleum, Rolls Royce and Jaguar. This was a sweeping ownership transformation.

In virus-affected economies, cash is king

In India, the government in March had to step in and rescue Yes Bank, an aggressive private-sector lender. State-owned banks account for over two-thirds of India’s banking assets. As the economy shifted into a lower gear, the problem of bad loans has risen. Prior to consolidation in 2017, there were as many as 27 public sector banks. Now, there are 12, including the State Bank of India—by far the largest. The banking landscape in Nepal is different, as only three of the 27 commercial banks are state-owned. But the virus-caused downturn will spare no one. It does not take long before a short-term liquidity crisis morphs into a crisis of solvency. Client defaults and bankruptcies will eventually roll up into the banking sector.

Some banks in Nepal likely will handle the crisis better than the others. Managements that knew business cycles better and prepared themselves accordingly could be in a position to acquire assets on the cheap. In fact, the publicly traded ones will probably do their shareholders a favour if they raise equity capital. The new funds may just come in handy if opportunities to acquire the weakest links come along. In a worst-case scenario, opportunities likely will be waiting for the cash-rich in most industries and sectors, including in hospitality where hotels for the last several years have been on a building spree. They were building at the top of the cycle, not the bottom, and there is a difference.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu