Columns

In development and poverty alleviation, every dollar counts

Nepal needs to invest more in data-oriented policy prescription and project evaluation.

Astha Wagle

In the early 2000s, Micheal Kremer, one of the winners of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics, and his team investigated ways to increase school participation among young children in Kenya. He tested the effectiveness of various propositions such as distributing free uniforms, providing free textbooks, introducing flipcharts in the classroom, providing midday meals and deworming children. In theory, all these methods could lead to an increase in school enrolment. So, which of these policies should the Kenyan government adopt? Similarly, which policies should the Nepal government implement if it wants to achieve the same goal?

This is where statistical tools and empirical data enter into the domain of economics. Evaluation of the implemented policies, using statistical methods and empirical data, gives us an estimate of the effectiveness and limitations of the policies. Kremer found that providing deworming medicines to school students was the most cost-effective way to increase the participation of students with an additional expenditure of only $3.50 per student per year. In comparison, other conventional and prevalent policy prescriptions, such as providing free uniforms or offering midday meals, cost $99 and $36 per student per year respectively.

Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Micheal Kremer—the winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences 2019—are the key personnel for developing and standardising this novel ‘experimental approach’ to evaluate policies in economics. For the last two decades, they have been contributing heavily to designing and evaluating policies that claim to reduce poverty in developing countries. They have empirically found the most effective policies from the pool of theoretical prescription in addressing the acute problems of poverty.

The revival and proliferation of development economics is largely associated with Banerjee and Duflo, who have carried out hundreds of randomised controlled trials with other economists and organisations, and have helped many developing countries climb up the ladder of poverty eradication. Today, their experimental research method dominates the field of development economics. Yet, only a handful of such assessments and evaluations have been carried out in Nepal so far. Nepal, a least developed country according to the UN with 41 percent of the population living under $3.20 per person a day in 2018, would be an ideal ground for the projects of many established and aspiring development economists.

Evidently, Nepal has a lot of potential to capitalise on this phase as it can offer researchers and analysts 'research ground'. If Nepal can ease the existing data constraints, it can induce more national and international researchers to carry out empirical research. Therefore, the government needs to invest in large-scale data surveys and data banks to attract researchers and their attention. The database at the least, if not the entire survey material, should be in English and in an exportable format.

Currently, policies are drafted without much data, research and consultations with the stakeholders. The culture of evaluating projects and policies is in a dismal state. If the priority of the government is to eradicate poverty or improve a key sector, implementation of policies is neither the first nor the final step. Policies should be launched by investigating the need for the place or people. Conducting a random survey to discern what the people—the beneficiaries of the policy—want should be the first step. After designing the appropriate policy in line with the needs of the people, implementing the policy is the second step. After the completion period of the policy, the third step is to properly evaluate, without inflating or deflating the numbers, the impacts of the policy.

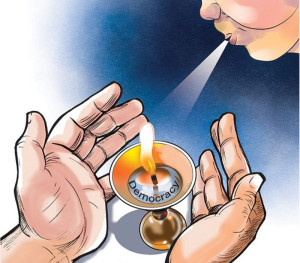

In the future, if we want to implement effective policies, it is crucial to evaluate the successes and failures of previously implemented policies. Given that Nepal or any other developing country has only a limited share of its budget allocated for alleviating poverty, a momentous leap can only be achieved if we can identify the most effective policies for poverty eradication in a particular area and launch it successfully.

Policies have been made and implemented since the introduction of governance. New methods are discovered over time, and Nepal should not fall behind in adopting them. The country, therefore, needs to invest more in data-oriented policy prescription and quality project evaluation. Designing and implementing appropriate policies can alter the rate of change of development and the alleviation of poverty while waiting for institutional reforms, according to Banerjee and Duflo. This strengthens the possibility for countries like Nepal to leap out of poverty when new and better institutions are being instituted. This brings a great deal of hope for Nepal, which aims to be a middle-income country by the end of this decade.

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu