Brunch with the Post

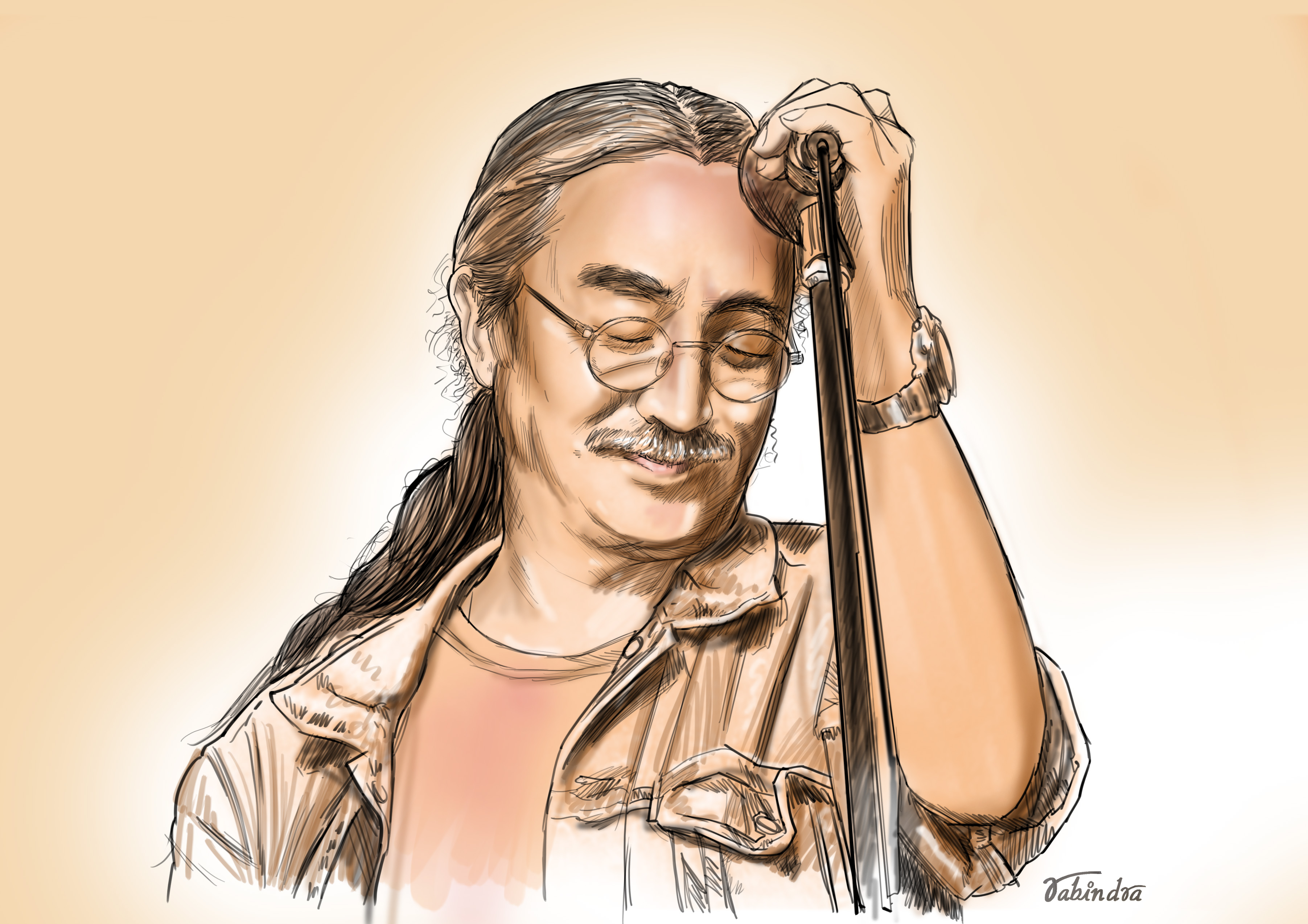

Dr Sanduk Ruit: ‘You can make history in this country’

The pioneering eye surgeon speaks about how he got into eye care, his work with cataracts and his infamous trip to North Korea.

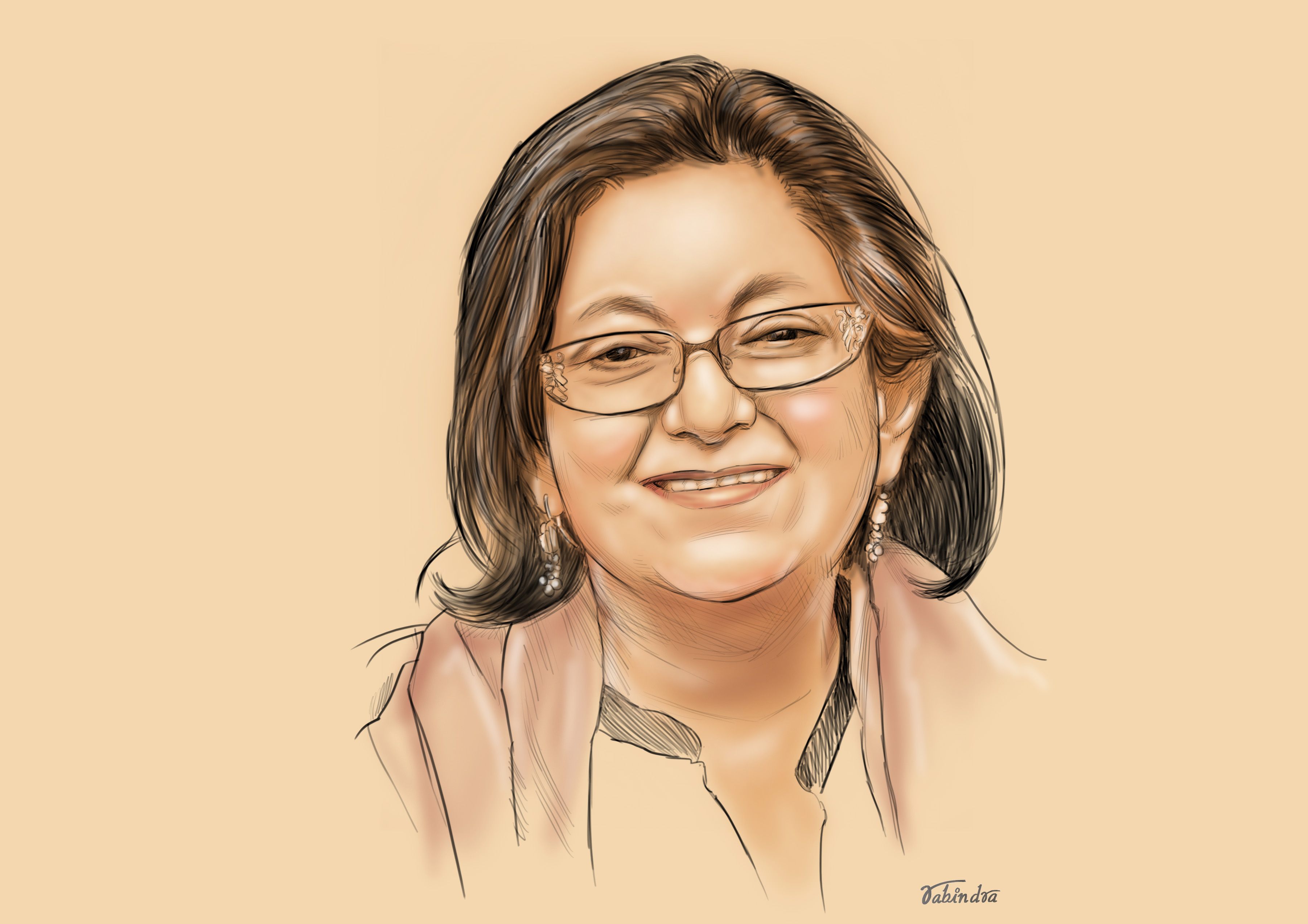

Pranaya SJB Rana

For a country bereft of role models, here is one man who is a shining beacon of honesty, integrity and selfless service. He’s directly changed the lives of over 100,000 people, and that’s a conservative estimate. And all without so much as a whiff of corruption or impropriety.

That man, of course, is Dr Sanduk Ruit, eye surgeon extraordinaire and founder of the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology.

As we sit down to eat at the Alice Restaurant in Gairidhara, Ruit’s manner is that of the consummate doctor, someone used to explaining difficult things to patients. I tell him that I visited him long ago for an eye checkup. So did my grandmother and my brother. He smiles.

[Related Story: A blind boy sees the light again, and the internet applauds]

“I’ve been doing this since the 80s,” he says, with characteristic equanimity and good humour. “Sometimes when I walk around Kathmandu, I feel like I know every third person.”

Ruit was most recently in the news for a viral video, where a young boy, upon being able to see, rushed over to the good doctor and kissed his face, erupting in an unrestrained, unadulterated expression of joy.

“It feels nice to be part of such a process, especially when it’s a young boy who has his whole life ahead of him,” Ruit says. “That really tells you how much of a difference you can make in someone’s life.”

This was just one instance that was caught on camera. It happens again and again, as the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof detailed in a glowing piece about Ruit in 2015. People who haven’t been able to see for years are suddenly brought into the light. Fathers see their daughters and sons see their mothers. But before that, they see Ruit, peering into their eyes.

“Everytime it happens, it tickles me and it’s a wonderful tickle,” says Ruit. “That’s the battery that makes me run. I think I’m very fortunate that I get to experience this over and over again.”

Ruit’s pioneering method of cataract surgery takes all of 15 minutes and can be performed anywhere, in a cowshed or a table out in the field. According to Ruit, he can perform seventy to a hundred operations in 12 hours, a marathon feat.

“I get tired, of course, but it’s almost like meditation for me when I get into that chair. I don’t feel the tiredness much because this is my opportunity to make someone’s life better,” he says.

He is humble to a fault, obsessed with making people’s lives better. It is a worthwhile obsession, one that few in the world will actually achieve. Ruit has already made thousands of lives better but he shows no signs of stopping.

Tilganga, the institute that he founded with five others and just $200, is one of the region’s leading ophthalmology institutes. The facility also manufactures intraocular lenses, the same lenses he uses in his cataract surgeries, which are on par with lenses developed in the West but at a fraction of the price.

“I want to take the intraocular lens factory to another level,” he says. “Right now, it’s like a non-profit, but I want to make it smart and commercial so that we can use its proceedings in our work.”

Ruit might be a doctor but he is also an extremely competent manager. Tilganga has flourished under his leadership because of his efficient management and a philosophy that everyone should be proud of the work that they do.

“In state-owned health care institutions, there are problems of bureaucracy, inefficiency and corruption,” he explains. “That has allowed the mushrooming of the private sector, all the way to the grassroots. That’s fine but the private sector only provides treatment to a certain section of society. The poor get left out.”

That’s where Tilganga comes in. Tilganga and its branches work on a social entrepreneurship model.

“We work like a not-for-profit but with extremely good business management and high quality care, as good as the private sector, but run with a better value,” says Ruit.

This is a replicable model, one that he’s already instituted at the Hetauda Community Eye Hospital.

At Ruit’s hospitals, eye care is provided on a sliding scale. Those who can afford it pay full price, others get subsidies or are even treated for free. At Tilganga, nearly half of their surgeries are performed at no charge. A cataract surgery costs Rs 7,000, but with a subsidy, it costs Rs 3,500 and if someone can’t pay at all, it costs nothing.

“Our hospital in Hetauda is community-based; it’s an achievable model and with cross subsidies, it is financially self-sufficient,” says Ruit. “After 10 years, it is now meeting operating costs and making a surplus. This model is being scaled in Indonesia, Ethiopia and hopefully in other places also.”

At the heart of the Hetauda hospital and Tilganga is employee ownership. They have a stake in the hospital they’re working for and that means they’re committed to the work that they do.

“Retainability of health care personnel is a big issue, not just in Nepal but all over the world. You cannot stay in one place if you don’t have ownership of the place where you’re working,” says Ruit. “For instance, if you work an extra hour and you get five dollars and five extra dollars go towards the institution, that’s a financial incentive but it also provides you with a sense of ownership of the institution.”

Now, with over 500 employees and partner organisations across the world, Ruit has succeeded. But it cannot have been easy for him to work in heavily bureaucratic and politicised Nepal, especially given his distaste for both red tape and needless politics.

“I’ve never been a file chaser,” he says. “Bureaucracy is such an important structure of governance but most of our bureaucrats are inefficient. The bureaucracy, like every sector of society, is divided from top to bottom along political lines. And all our professional bodies, whether it is medical or engineering, have been politicised. That’s the essence of inefficiency.”

[Read: How Nepal’s oldest hospital, and the government that runs it, continue to fail the country’s poor]

There were attempts to politicise Tilganga too, but Ruit never stood for that. It’s one of the things he’s most proud of, he says. At the very beginning, some people took an issue with his working style and went to complain to the then prime minister, Girija Prasad Koirala.

“What they didn’t know was that I had worked on Girija Prasad’s eyes,” Ruit says with a laugh.

Ruit’s interest in eye care was kindled early in his career. He started out as a general medical officer at Bir Hospital, assisting the senior doctors. It was on a trip to the West with NC Rai, an eye doctor, that he first saw how a simple operation could change a life. A family from Dadeldhura had come to the eye camp that Rai was running. Four of the children had congenital cataracts, all of which Rai operated on.

“The process struck me,” says Ruit. “In such a short time, you could make such a difference in people’s lives. It was then that I thought maybe this is what I want to do.”

In 1981, Nepal released its first national blindness survey, which showed that 60 percent of people who underwent cataract surgeries were still functionally blind as they had to wear large, very thick glasses. Around five percent had iatrogenic blindness—blindness created by surgeons. The success rate of surgeries alone was around 40 percent. This upset Ruit. He wanted to make a difference but if surgeries were so fraught with complications and risks, what was the point?

There needed to be a different way. Ruit formed a small team of like-minded individuals and began to work with intraocular lenses that they received from American friends.

“But I started to think about how we could do the same kind of microscopic surgery that they do in New York, London or Sydney in a place like Nepal in a cost-effective manner,” says Ruit. “I spent around five years just thinking about this problem. Eventually, I managed to fine tune the surgical process using intraocular lenses.”

But despite Ruit’s new method, which drastically reduced the time for surgery, its cost and even post-operative complications, the international community wasn’t impressed. The World Health Organization and Western ophthalmology institutes dismissed his method. But Ruit wasn’t one to give up so easy. Along with his mentor Fred Hollows, he presented a case study of 150 people in rural Nepal who’d undergone surgeries using intraocular lenses. Still, there was resistance. It was only after they published a paper in the American Journal of Ophthalmology—in 2007, almost a decade after pioneering his method—that people slowly started to come around. Now, doctors come from across Asia and Africa to study the method at Tilganga.

“When I look back, I can’t believe I’ve come this far,” says Ruit. “But looking at what we achieved in the last 10 years, I believe we can achieve much more.”

Ruit sets his goals high and surprisingly, he’s achieved them time and again. After a cataract surgery delivery rate survey placed North Korea on top, Ruit decided he would go to the reclusive country. He just didn’t know how.

Perhaps it was fated that a North Korean embassy official, who spoke Nepali very well, walked into his New Road clinic.

“I immediately asked him to come visit our hospital. After about a week, he came and toured our facility. Then, he said in Nepali, ‘tapai haru le ta Nepal ma ankha ko kranti gareko rahecha’. I asked him if we could do the same in North Korea,” Ruit says, recalling his conversation with the North Korean official.

After three months, the North Korean official told Ruit that his government was willing to allow him and a small team to conduct surgeries in the country. His first trip, where he operated on people in Pyongyang and Haeju, was a roaring success and he was invited back. This time, he was allowed a television crew, who filmed the infamous documentary Inside North Korea.

But his globe-trotting days might be over, at least for the near future, because Ruit wants to focus on Nepal. He has just two districts left to visit--Humla and Darchula--and he plans to get there soon.

Before we leave, I tell him that he is widely admired and that so many look up to him. He has advice for the young.

“This country has a lot to offer. There are so many opportunities here when the rest of the world is getting saturated,” he says. “There’s a difference between going somewhere everything is already built and building something yourself. Life is not what you see in five years, it’s what you see in fifty years. You can make history in this country.”

ON THE MENU

Alice Restaurant, Gairidhara

Sliced Fish Peking Style: Rs 375

Mackerel Lunch: Rs 700

Yaki Gyoza: Rs 365

Americano: Rs 145

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg)