Brunch with the Post

Rekha Thapa: Women weren’t born daughters, we were made daughters

The fiery actor speaks about breaking conventions in Nepali film, her passion projects and how she ended up in politics.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Picture a serene lake, its waters placid and calm. A rock drops and breaks the surface tension, sending out ripples that spread across the lake. And suddenly, the lake isn’t that tranquil anymore.

If that body of water is the Nepali film industry, then that rock, by her own admission, is Rekha Thapa.

“I kicked my way into the film industry in a skirt,” she says, confident, assertive, outspoken—every bit the Rekha Thapa you have come to expect. “If I was going to aim a kick at someone, I wasn’t going to do it in a sari.”

Thapa, at just 16, came into the film industry like a wrecking ball. At a time when female Nepali actors were meek and subservient accessories to their male counterparts, Thapa made a name for herself as a no-nonsense, kick-ass actor.

That was in 2000, and Thapa says she wasn’t exactly welcomed with open arms by the male-dominated Nepali film industry, nor by Nepali society at large.

“In my early days, people criticised me, saying I was corrupting young women by telling them that it was okay to wear skirts and shorts, by saying they shouldn’t fast on Teej if they didn’t want to, and that it was okay to keep your own last name even after getting married,” says Thapa. “I was even boycotted by some people in the film industry.”

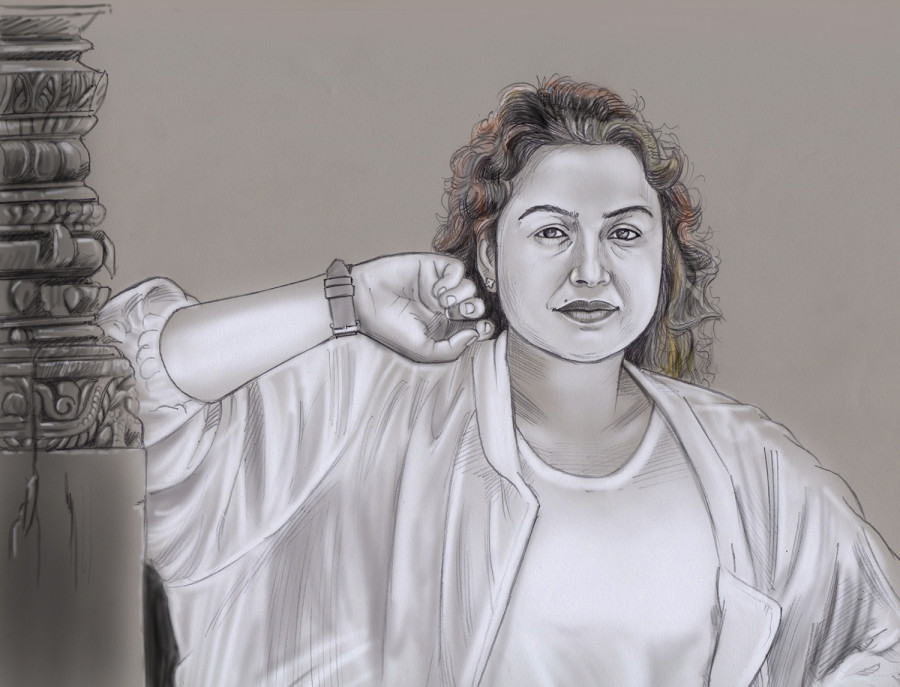

Nineteen years and over a hundred films later, Thapa remains an unstoppable force in the Nepali film industry. But she’s gone through a visible change. In her own words, she’s become older, wiser, calmer and more relaxed.

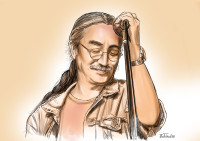

When Thapa proposed meeting at Dwarika’s for brunch, because we’d likely have to shoot some photos, I’d expected her in glamorous diva mode. But what we saw was Thapa unvarnished, with no makeup or fancy dresses. She was down-to-earth and effortlessly relaxed, kilometres from the Rekha Thapa of films like Himmatwali and Rampyari.

Thapa says she owes all of this to her life coach—Nar Bahadur Karki, who was recommended to her by a politician. She wouldn’t name the politician.

“Life is a game and I’m here to play,” she says. Over the course of our conversation, I discover that Thapa loves to speak in metaphors.

“But I need guidance,” she continues. “I need a coach to show me where and how to score a goal.”

Her coaching sessions have helped her let go of her ego, she says. She’s less combative and hostile these days, letting inconsequential things slide.

Thapa is focused on more important things at the moment. She’s preparing for a film, so she works out every morning at her home gym. And although she’d agreed to meet for brunch, she professes wanting to eat nothing, except drink coffee and smoke cigarettes. When I insist, she finally agrees to a fruit platter.

But back to her work. Thapa produces her own films now, through Rekha Films, and the kinds of films she takes up are markedly different from what she did for others.

“I’ve had enough of doing films where the woman is just running around the man,” she says emphatically. “Women aren’t just ornaments.”

This is largely what led her to start her own production house. All across Nepal, Thapa is known as the only female actor who consistently beats up the bad guys all on her own, who doesn’t need a man to save her. She’s attempting now to bring that rebellion to women’s issues, something she is greatly passionate about.

“It is my desire and my responsibility to show girls that they can lead a society,” she says. “They can do whatever they put their minds to. I want to show girls all over Nepal that even they can become heroes.”

This then is her pet project, to help produce the next generation of Rekha Thapas who will step into a patriarchal industry and break it apart. After all, there are few celebrities who are beloved across Nepal like Thapa, except for maybe Rajesh Hamal. Her last film Malika, which she produced and directed, is about child marriage and while it might be campy and over-the-top, it’s the kind of film that Thapa has become known for. At its heart is women’s empowerment, even if it comes through copious beatings handed out by a stern Thapa.

“I don’t live by anyone else’s rules and I don’t think anyone else should either, especially women,” she says, stating what has become obvious to everyone who’s followed her career trajectory. “Women weren’t born daughters, we were made daughters.”

There are echoes of Simone de Beauvoir in what Thapa said. Beauvoir, in the classic feminist text The Second Sex, wrote, “One is not born, but rather, becomes a woman.” Thapa too is speaking about the performativity of being a woman, where women are taught, since birth, what boundaries exist for them and how not to transgress them.

By all definitions, Thapa should be a feminist but she is ardent about how she’s not a feminist.

“I wouldn’t call myself a feminist. I’m just someone who can tell the difference between justice and injustice,” she says.

Her disavowal of the label of feminist appears to stem from the misconception that feminists hate men and all they want are quotas for everything.

“I want to work with men, not against them,” she says. “I’m also against quotas. I don’t want a quota. I want to run against men on the same field. I might lose, but I want to be given the chance to compete and win on my own terms.”

Her ideals are in the right place and though I might disagree with her, I can understand the depth of her conviction that women do not need handouts; they just need opportunities to prove themselves.

“Why should I have to eat out of the plate you give me,” she says, nibbling on a piece of over-priced fruit.

She believes that quotas once again turn women into “daughters”—as in, women are again beholden to men and their paternal generosity. Coming from Thapa, who is so used to breaking noses and taking names, this is not wholly unexpected. She just wants to see women succeed on their terms. But before this can happen, there needs to be representation. Young women, especially from the rural parts of the country, need someone to look up to.

Just like Bipin Karki told me a few weeks ago, there is a clear rural-urban divide in Nepali films. The films that urban Nepalis are watching do not do well outside of the cities and Thapa believes, this comes down to representation.

“There’s not enough authenticity in our films,” she says. “We can’t make films where the actors are speaking in Nepali with a foreign accent. Nepalis from across the country should be able to understand the Nepali I speak. We need to think about who we are representing on film.”

Thapa believes that this issue with representation is not just limited to films—it is perhaps most apparent in beauty pageants, which she has contested. Thapa won Miss Koshi before she began her film career and later, even participated in Miss Nepal, where she was placed in the top ten.

“Beauty pageants by themselves aren’t bad,” she says. “But we’re neither here nor there. Our Miss Nepals don’t represent Nepal and they can’t compete internationally either. Which class of Nepali society does Miss Nepal represent? Can a girl from Karnali dream of becoming Miss Nepal one day?”

Thapa’s beef with Miss Nepal is the same complaint she has against ‘urban’ films, that they provide an image of the Nepali woman that is alien. She doesn’t buy the argument that beauty pageants empower women, as she thinks they only empower a certain kind of woman.

“If we’re going to talk about empowering women then why does a Miss Nepal contestant have to speak English with an accent?” she says. “Why does she always have to be glamorous and attractive?”

This problem with representation starts at the very top—with political leadership. Thapa can’t think of a single female politician who she believes is doing good work.

“Women politicians are still not in a position to make changes,” she says. “A lot of them came in through proportional representation, while others got their place because they were related to men in power. Until and unless a majority of women are contesting and winning elections, they won’t have power.”

This is why Thapa decided to get into politics. She once made headlines for joining the Maoist party and subsequently dancing with Pushpa Kamal Dahal. Since then, she has quit the Maoists and joined the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, of which she’s a central member and head of the party’s foreign department, she says.

“Politics is a good thing,” she says. “I might stand on the street and yell for months, but with the stroke of a pen, a minister can make what I demand a reality. That’s where I want to be.”

She got into politics to change the way Nepali society views politicians—as corrupt, inefficient, self-centred. She believes that people should only get into politics once they have achieved a level of success in their professional lives.

“I’m someone who’s already contributed to society so no one can point a finger at me,” she says. “All politicians should have another job, and they should do politics only once they’ve become accomplished in their field. That will prevent corruption.”

It’s only natural for someone who came from nothing to want to build something for themselves. That’s why politicians become corrupt.

“Every tenant wants to buy the house they are rented,” she says.

Thapa is greatly affected by the continuing plight of women across the country. She is in disbelief that even with a woman as the country’s president, a case like that of Nirmala Pant can go unresolved for over a year. All of this, she believes, is symptomatic of the manner in which this country has failed its women.

“Women constitute more than half of the population, but in society or politics, where are the women?” she says. “Nepal is on a highway to progress, but where are the women on that highway? We’re on the sidelines, on a narrow, unpaved road, watching the men pass us by. We’re just spectators.”

Dwarika’s Hotel, Battisputali

Pot of coffee: Rs 270

Cappuccino: Rs 390

Fruit Platter: Rs 490

Fido Maki: Rs 1,057

Mushroom Tortellini: Rs 600

11.19°C Kathmandu

11.19°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)