Brunch with the Post

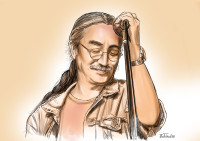

Bipin Karki: You need to be a good person to be a good actor

Karki takes months to prepare for a role, especially if its something he's unfamiliar with.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Bipin Karki is late. It is 45 minutes past noon when he makes his appearance, riding in on an aquamarine Vespa, in shades and a baseball cap that reads ‘Do you know?’

He sits down and immediately reaches for a cigarette. The shades don’t come off.

As he fingers his cigarette, Karki talks softly, in a kind of lilting Nepali drawl that is unaccented by the kind of pretensions that many in the Nepali cinema industry have adopted. He says ‘raag’, ‘satis’, ‘bro’ without any hint of irony—that’s just how he talks.

We speak about his new film, which is apparently called ‘Selfie King’.

“The name might seem commercial but I don’t think it will be a commercial film,” says Karki, looking at me through his ochre-coloured shades. “It’s the story of a comedian, who’s recently become successful. In a way, it’s the story of what has happened to me.”

He’s right. Karki’s fame has been almost instantaneous. Seven years ago, he came out of nowhere and now, he’s in almost every Nepali film that receives some critical appreciation. His breakthrough role was as the raspy-voiced bald-headed Bhasme Don in Dipendra Khanal’s Pashupati Prasad. He won accolades for his uniquely charming portrayal of an aryaghat goon and has since gone on to play a variety of different characters—the dreadlocked Pitle Don in Loot 2, the mohawked Goldie in Naaka, a slow-witted convict in Bhaskar Dhungana’s Suntali, and a straight-laced office-worker in Pratik Gurung and Safal KC’s Hari. He’s a chameleon, changing physical appearance, tone of voice and body language with every new role.

“Maybe it’s my face,” says Karki, when asked about the ease with which he sheds old skin for a new ceremony. “I think I just have that kind of face where it’s easier to look different.”

But it’s not really his face; it’s his method. He’s a painstaking actor who takes months to prepare for a role, especially if it’s something he’s unfamiliar with. For Pashupati Prasad, he spent weeks at the Pashupati Aryaghat, living among the vagabonds, drifters and young boy gangs of hustlers and glue-sniffers. They were wary at first, he says, but eventually, they adopted him as one of their own.

“I became friends with them so it became awkward during shooting,” he says, adjusting his sunglasses. “They all thought that I was so lucky to have gotten a part in a film. They’d wait for me, saying let’s go out after you’re done.”

He was so convincing in his role that the police nearly arrested him during shooting. During a scene when he was chasing Khagendra Lamichhane’s character around Pashupati, the police rushed him and nearly took him in before the production managers intervened.

He did the same thing for Kalo Pothi, even though he had a small part. To prepare for his role as a Dalit from Mugu, he went and lived with a Dalit family for two months before shooting even began. He ate with them, slept on a pile of straw, walked around with the kids and even joined them as a musician during Dashain. He wanted to get the dialect right, he says.

“For a while, I became that character,” Karki says. “If I stumbled, I’d allow myself to fall, thinking I should fall like a character, as if a camera was constantly filming me.”

This is Karki in a close-up, intimate. He speaks casually, off-hand, as if these are things everyone does. He alternates between self-effacing and ardent, going from one to another in the space of a second.

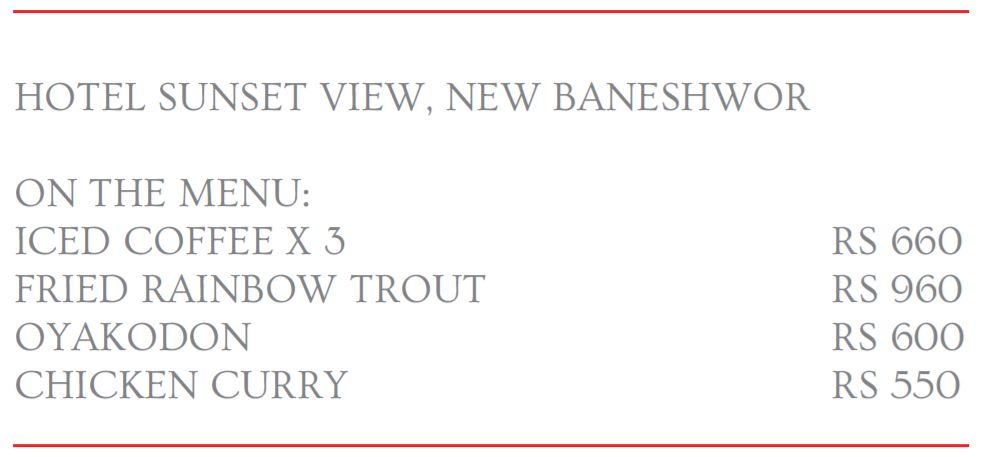

Sunset View is an oasis in the chaos that is Baneshwor. I had heard that it also had good Japanese food, but Karki doesn’t seem particularly interested. The restaurant is empty, ghostly and dark, and the middle-aged servers don’t seem particularly interested in us. It takes a few minutes to get them over and Karki eventually orders the fish. He wants to try the fried rainbow trout.

By the time the food arrives, suspiciously soon, we are talking about his recent Best Actor win at the National Film Awards for his role in Prasad. It’s not something he’s particularly proud of. He wanted to be nominated for his role in Hari, the off-beat, dark comedy that won critics over but the box office ignored.

“Hari is special to me; I really liked that film,” he says. “But neither the audience nor the awards people even considered it a film.”

In Hari, Karki plays the titular character, a meek, buttoned-up office worker whose routine life gets thrown out of whack when he attempts to fire an annoying co-worker. Karki plays four different characters in the film and he is alternatively funny, sad, pathetic and sympathetic. I can see why he likes the film so much—it allowed him to showcase his range.

“I was sad that Hari didn’t even get a nomination but that shows where our film fraternity currently is,” he says. “The jury needs people who understand the film. I don’t think they understood Hari. Everyone talks about how Nepali films need to be different but the awards don’t even recognise films that are unique. That’s our misfortune.”

Karki is, of course, right. Hari was arguably last year’s best film but the Best Film award went to Gopi, which also stars Karki as an aspiring cowherd. Gopi was by no means a bad film; it had a unique premise and was filmed beautifully. But Hari was unique, it was an attempt at that very rare commercial-art film chimera, with immaculately composed shots and a variety of quirky characters.

So what happened with Hari? It ran for barely a week in theatres and then disappeared.

“The Nepali film audience needs to laugh. If they don’t laugh in a film, they get upset,” he says. “Hari was a comedy, but it was a satire and that was its problem. The Nepali film-going audience doesn’t like that kind of dark comedy. The audience has been trained in a certain way, watching Bollywood and all the Nepali films that knocked off Bollywood.”

This is understandable, Karki gives his caveat. The fried whole rainbow trout is difficult to eat with a knife and fork, so Karki has switched casually to his hands, and this is where he delivers his monologue, where he stands in front of the audience and says his piece:

“No one recognises me in the villages; they only know who I am in the cities. There’s a distance between the cities and the villages. People in the villages want comedy, because they want a distraction from their lives. They don’t want misery and sadness when they spend their hard-earned money on a film. They want to laugh and forget their troubles.”

It is not the audience’s fault for wanting what they want. Film is largely entertainment. It is popular culture and what is popular is not necessarily what is good or artistic. But it is also the film industry itself that needs to introspect and think about what it wants to be—Bollywood’s younger, less-attractive cousin or something wholly different.

“Nepali film doesn’t have an identity,” says Karki. “Chinese, Iranian, South Korean, and even Vietnamese films have their own identity. But that’s never been the case with Nepali films. We never had a Satyajit Ray.”

There are films that are uniquely Nepali, Karki concedes, but they are a small minority, like Min Bahadur Bham’s Kalo Pothi or Deepak Rauniyar’s Seto Surya or Tsering Rhitar Sherpa’s Mukundo. These are all art films, films made for the festival circuit, not really for mass public consumption. And they’re all mostly funded by foreign backers, not Nepali producers.

“Nepali producers expect films to make money, they don’t see films as art,” says Karki as the sunlight bounces off his glasses.

In the end, it all comes down to how we’ve been schooled, he says. How we grew up, what we learned in school and how we came to films—all of that figures into the kind of films we consume and the kind of films that get made.

Karki himself came to acting almost accidentally. He was a literature student at Ratna Rajya Laxmi Campus when he started going to see plays at Gurukul. That was when he knew he wanted to act and so, he embedded himself into Gurukul, doing odd jobs backstage. He was picked for small roles and as an extra. But it took Deborah Merola of One World Theatre to cast him in his first big role, as Peter for a Nepali adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms.

From there, there was no stopping Bipin Karki. He worked alongside Saugat Malla, his one-time roommate, under the tutelage of veteran theatre director Sunil Pokharel, who would cast him in what is Karki’s favourite role so far. Pokharel had adapted Akira Kurosawa’s legendary film Rashomon for the stage and cast Karki in it.

We have spent close to two hours talking. He is not shy but he is not voluble in the way many actors are. He says he wants to play an upper class, rich person next, because that’s a role he’s never done. His characters are down-to-earth, homely, salt-of-the-soil kind of people. He wants to play a frivolous character, rich and easy-going who drives around in a Mercedes.

As we’re wrapping up, I ask him to compose his dream team of co-stars and filmmakers. It takes him a long time, thinking it over. He finally comes up with a list—Mahesh Bikram Shah, if he ever wrote a screenplay; Safal KC and Pratik Gurung, the directors of Hari; Saugat Malla and either Menuka Pradhan or Swastima Khadka as co-stars.

Karki might have made a name for himself as a character actor, someone who’s adept at getting into someone’s skin, but it is clear he is most comfortable in his own. There is an ease to his way of speaking and sitting. His body language is that of a well-practised actor. But I wonder about his sunglasses and if you can ever really get to know someone whose job it is to become other people.

So what does it take to be a good actor?

“You need to be a good person,” he replies. “And by that, I don’t mean you have to be good looking. You need to be able to empathise with people, their sufferings and their joys. You need to be able to feel what they feel. You also need to be able to call out injustice when you see it. You need to be a good person before you can be a good actor.”

Karki drives away in a long shot, held long after he’s exited the frame. The sunglasses never came off.

10.21°C Kathmandu

10.21°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)