Brunch with the Post

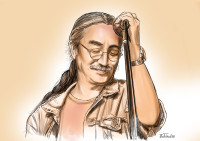

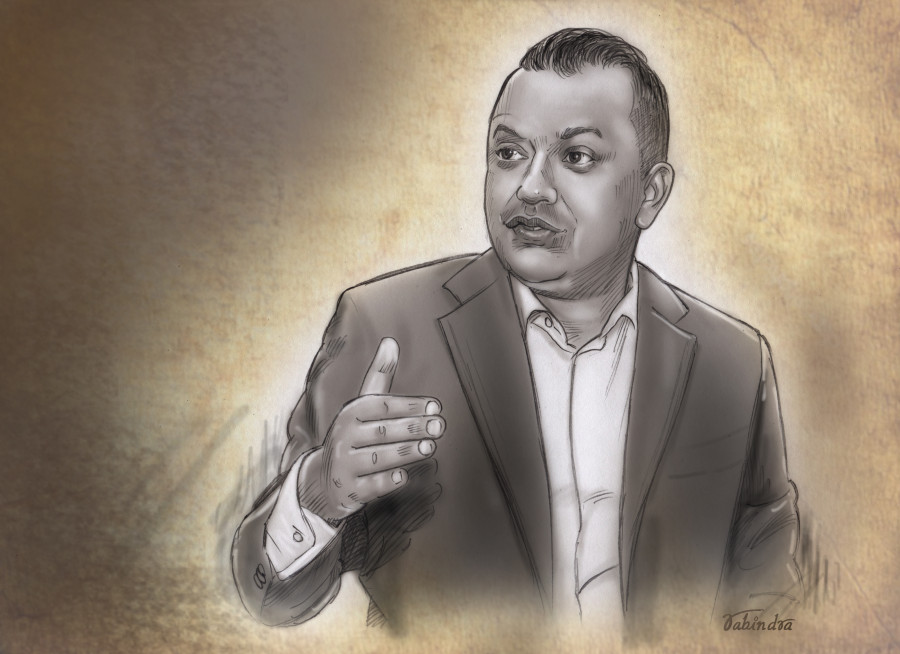

Gagan Thapa: The young people of today can’t connect with Congress

The Nepali Congress leader talks about institutions, his party, and the ministry he’d like to lead next time.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Gagan Thapa believes in institutions.

Nepali society is constantly looking for heroes, some Nietzchean ubermensch to take charge and do what is necessary. Whether in politics or governance or even civil service, Nepalis want superstars.

But Gagan Thapa believes in institutions.

“Heroes can turn 19 into 20,” he says. “But to get to 19, you need institutions.”

One might argue that Thapa himself is such a hero. He is one of the most popular politicians in the country, known for his fiery oratory and his insistence on telling it as it is. His outspoken activism against Gyanendra Shah’s autocracy and his visible leadership during the second People’s Movement won him legions of admirers. But for Thapa, that popularity is both a boon and a curse.

“I am a beneficiary but also a victim,” he says affably, but is insistent on the importance of institutions. That absence of institutions determines Thapa’s morning routine, where people from all over the country come to his office, like in a scene from The Godfather, asking for favours.

“The things they ask for say a lot about the state of our country,” says Thapa. “A man came to me today asking for help because he needed a family member admitted to the trauma centre but there was no space. If the system was functioning like it’s supposed to, he wouldn’t have to come to an MP and ask for help.”

We’re sitting at Imago Dei, chosen for its proximity to Thapa’s workplace. Thapa is on the 16:8 diet, which is basically a form of intermittent fasting. He doesn’t eat after a certain time in the evening and only eats the next day, at lunch.

“It really makes you appreciate the flavour of food,” he says, ordering a grilled fish with steamed vegetables.

We first talk about his family. Thapa and his wife, a doctor, have two daughters and many-a-time, he can be glimpsed around town, two little girls in tow. Clearly, the family is extremely important. He relates an anecdote about Shankar Pandey, a Nepali Congress leader from Syangja.

“He once showed me a picture of George Bush on the beach in his shorts and with his dog and he told me, ‘Babu, our politicians seem to confuse being asta-byasta with being byasta,” says Thapa. “Always remember to take time out for your family.”

Thapa has taken Pandey’s advice to heart, blowing off important programmes to be with his daughters and his wife. Once, a number of MPs had even decided to not attend any programmes on Sunday, in order to spend that day with our families, he says. But of course, that never happened.

Thapa is open, gregarious and erudite. He is easy to talk to and the conversation is wide-ranging, covering everything from his recent time at Harvard’s Kennedy School and his family to politics within the Nepali Congress and his evaluation of the current government. But each time, he comes back to institutions.

Thapa’s occupation with institutions is not out-of-character. He is one of the few Members of Parliament regularly present in the House, speaking often as a member of the opposition Nepali Congress. He believes it is important to take part in the institution of the Parliament as an essential democratic exercise.

“In other countries, politicians need to answer to their constituencies about the positions they take on certain bills,” he says. “But here, no one really knows what anyone else said, and often, no one is even speaking.”

Thapa is a second-time Member of Parliament and a former health minister, so his belief in the value of institutions is not merely wishful thinking; it is born out of more than a decade of politics. But perhaps it was also hammered in during his time at the Harvard Kennedy School, where he took part in a short course on governance with young leaders from across the world.

“It was a great experience,” he says. “I’d always had a desire to take a break and go abroad to study. It was the full college experience that I never really got in Nepal because I got into politics as a student.”

Thapa made his bones as a student leader, rising through the ranks of the Nepali Congress’ youth wing, the Nepal Students Union, during his days at Tri-Chandra Campus. Since then, he’s slowly climbed up rung by rung, eventually becoming a member of the party’s Central Working Committee. But he’s not wholly happy with the manner in which the party has been functioning.

“Who is the Congress now?” he asks. “We keep talking about BP [Koirala] and the past. The young people of today can’t connect with the Congress.”

Thapa believes that the Congress doesn’t have a strong unifying narrative anymore. Earlier, it was Girija Prasad Koirala who provided the party’s narrative of bringing the Maoists into the mainstream and writing a new constitution. But now that both those tasks have been accomplished, the party appears lost, he says, and it doesn’t know what it wants.

It is precisely this confusion that is leading the Congress party to become an ineffective opposition. In between bites of his basa fish, Thapa cites Yogendra Yadav, an Indian social scientist, to describe the Congress.

“According to Yadav, the Indian Congress employs a politics of opposition, not a politics of alternatives, and that’s what I believe the Nepali Congress is doing,” says Thapa. “People want to see us as an alternative, but we need to earn that trust. If we’re going to tell the people to vote for us, we need to tell them what we’re going to do differently. People don’t want to hear what the current government is not doing; they want to hear what we’re going to do.”

Thapa wants the Congress to have a mission again, something it can believe in beyond platitudes singing BP’s praises. But that is going to be hard, given recent developments in Nepal’s grand old party where regulations limiting internal criticism are being passed. Thapa believes that the new regulations stem from a desire to emulate the structure and tactics of the Nepal Communist Party, like the Trinamool Congress did in West Bengal by emulating the Communist party there.

“There is one school of thought that believes that we need to make the party more hierarchical, so that there is order in the party. So there is no space for criticism and dissent,” he says. “But there’s another school of thought and that’s the one I believe in—the party needs to be more open and liberal. We need to admit our past mistakes and try to address them. Then, our identity will be different from that of the NCP.”

This tendency towards discipline through order is borrowed straight from the KP Sharma Oli administration, where dissent and criticism are limited and the prime minister actively encourages his party members to not criticise his government. Discipline cannot be instituted by using the stick, says Thapa. It’s a mission that establishes discipline.

As he talks about discipline and order, Thapa beckons over a waiter. He wants something hot, maybe a chili sauce, for his fish. The waiter suggests hot sauce but Thapa wants something else. He settles for chili flakes. It appears that Thapa likes his food spicy, or perhaps the basa and steamed vegetables are a little too bland.

“The prime minister’s narrative of progress is old fashioned,” Thapa says. “It is obsessed with large-scale infrastructure projects. I would suggest that he first fix the basics, like service delivery. Our public service delivery is very poor and the prime minister hasn’t paid attention to that at all.”

All of this criticism is informed by Thapa’s own time in government, as health minister in the Pushpa Kamal Dahal administration. Thapa is as critical of himself as he is of others, evaluating his tenure as minister as something he would like to change.

“Looking back, 60-70 percent of the work I did, I would do differently. How I handled my bureaucracy, how I worked on short-term and long-term policies,” he says. “My time in the Health Ministry taught me a lot of things that I wish I could take back to the beginning of my term.”

Thapa was a first-time minister and since then, he’s had time to learn, reflect and grow. If he ever gets back into government, he says it will be in the Ministry of General Administration.

“The civil service is underrated and it is underused, but it is a major part of the government,” says Thapa. “Right now, with the country going to federalism, there is a massive opportunity to make use of the civil service.”

Not a very sexy choice of ministry, but again, it reflects Thapa’s unflappable belief in institutions. The bureaucracy is Nepal’s most ossified of institutions and one can wonder what a dynamic young leader like Thapa could do with a ministry like that. Either he would chew up the system or the system would chew him up.

We’ve finished our food and we’re on our coffee now. As he sips his latte, the conversation shifts to ambition and legacy, and Thapa grows circumspect.

“Later, when I retire from politics, my daughters will have grown up and they will look back at their politician father. What will they see?” he says. “I could either be someone who became an MP five or six times, or a minister or a prime minister two or three times. Or I could be someone beloved by the people for doing his best in whatever capacity he had. I’d prefer the second kind of legacy.”

Imago Dei, Gairidhara

On the menu:

Grilled fish with steamed vegetables: Rs 820

Spinach and cheese ravioli: Rs 630

Chicken spaghetti: Rs 660

Cold coffee: Rs 150

Fresh lemon soda: Rs 120

Espresso: Rs 110

Latte: Rs 135

9.4°C Kathmandu

9.4°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)