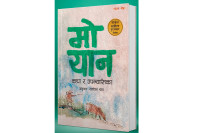

Books

Caught between art and anguish

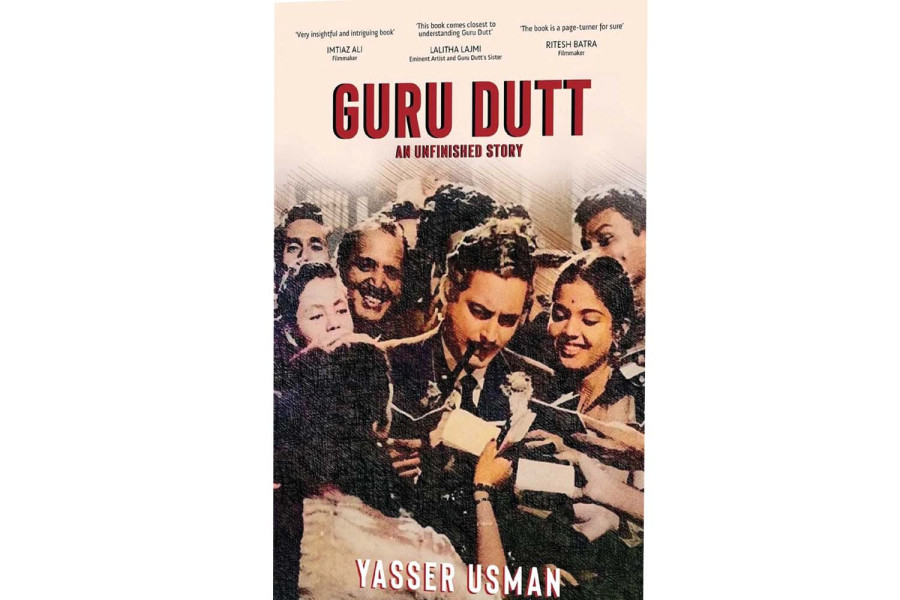

Yasser Usman’s ‘Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story’ offers an intimate look at the complicated life of the Indian filmmaker.

Anish Ghimire

For many, no matter how materially rich they are, melancholy never leaves. One of cinema’s all-time greats, Guru Dutt, had a similar life. Enduring sadness remained integral to his life and the projects he wholeheartedly made. The films he directed, produced and acted in reflect the turmoil he battled daily in his glamorous life.

Yasser Usman’s ‘Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story’ covers much of his life and the people who shaped it. Usman, a reputed Indian journalist and writer, has brilliantly summarised the highs and lows of Dutt’s short career. The writing is pacy and descriptive. The explanation without any melodrama is still absorbing. Most importantly, the book is well-researched and avoids taking any sides. One could have easily been carried away, but the author preserves the strict nature of reportage.

The writer cleverly starts the book by taking us back to 1963 when ‘Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam’ was being shown at the Berlin Film Festival. The film wasn’t received well, and Dutt walked out of his own screening. This happened at the time when Dutt’s marriage with Geeta Dutt was in shambles, and his relationship with actress Waheeda Rehman was turning cold. From Berlin to Bombay (present-day Mumbai), he drank the entire way, even using all the sleeping pills he had carried—yet his insomnia kept him awake for four nights in a row.

Beyond the camera

For Dutt, it was very important how the audience reacted to his projects. He took the failures hard and remained grounded during success. He often kept to himself and steered clear of expressing his feelings. The only time he was expressive was when he was making films.

Dutt’s sister, Lalita Lajmi, who drives the narrative, says in the book, “Guru Dutt was a workaholic. Nothing mattered except work. Also, when he was upset, he would go quiet. He would never share what’s going on in his mind.” Lajmi, a celebrated painter, was artsy and creative like her brother. This perhaps came from their father, Shivashanker Rao Padukone, who found refuge in books and poetry. Lajmi remembered her father as a “laid-back individual who didn’t talk much.”

The author’s choice of narration, starting with Padukone’s in-direct influence on his children, provides a valuable background on Dutt’s life. We learn about their financial hardships, with Padukone juggling jobs and many mouths to feed. The book offers a personal glimpse into Dutt’s life, revealing why he often felt “baffled with life”.

The great actor Dev Anand, who remained close to Dutt throughout his career, said, “He suffered from melancholia. He was a good man, a good thinker, but a back-bencher. He never wanted to be part of a crowd. He was shy but good at his work.” Such quotes throughout the book from Dutt’s close circle provide intimate details about the man he was.

A pluviophile perfectionist

Despite battling his inner demons and personal life, Dutt was relentless when it came to work. He was impatient, uncompromising and a perfectionist. He’d rather give up the project than settle. Throughout his career, he scraped many films for different reasons—some logical and some not. He was infamous for being short-tempered and hard to work with, as he demanded strict discipline from his workers. He kept re-shooting a particular scene until he was satisfied. For ‘Pyaasa’ (1957), Dutt’s classic, he shot the climax scene 104 times! But it’s not like he was sure of what he was doing—most of the time, he remained unsure of what he wanted in a scene.

His wife, Geeta, a singer with a soothing voice who sang for many of Dutt’s movies, said, “From where does the inspiration come which causes those divine fires in the creator...his passion for perfection, the zeal which makes him forget people, circumstances, and the mundane, everyday realities.”

Apart from his passion, perhaps this act of ‘forgetting people and everyday realities’ was why Dutt remained so devoted to his work. He worked all day, sometimes refusing to visit his home and retiring to his farmhouse, Lonavala. There, he worked on what he could; whether it was farming or filmmaking, he kept busy. But he had a soft corner for rainy days. On such days, he let loose, dropped his shoulders, eased himself and ran outside.

Amid the complexities of life and inside the tough exterior, Dutt was a child at heart. The author does well to go deep and pluck out such details—humanising the filmmaker. One day, when his team was working in Lonavala, it began raining. Dutt’s face lit up, and he pulled everyone outside, and they went for a long drive. When asked to drive slowly, he responded, “Why, are you scared?”

Upon returning, he pulled out a chair and watched the rain for hours.

Thin line between real and reel

Usman’s description of the making of Dutt’s famous movies like, ‘Pyaasa’, ‘Kaagaz Ke Phool’ (1959), ‘Chaudhvin Ka Chand’ (1960) and ‘Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam’ (1962) is lively. The process, from the casting to the reviews published at the time, is woven into the narrative. This makes for an engaging read. However, the disordered nature of storytelling might be off-putting. We go back and forth from the 1950s to the 1960s—focusing on Dutt's beginning and later career. A seamless timeline, from the beginning to the end, might have been an easier read.

But take nothing away from this richly detailed and simple book of a not-so-simple man.

In this read, we also learn about Dutt’s famous filmmaking style—the line between real and reel was minimal. His movies inspired by his life—were too personal and close to heart. This is also the reason why he took the failures hard. A famous example is ‘Kaagaz Ke Phool’. Despite warning from his close circle that the film might be too personal, Dutt went on with it. The autobiographical movie mirrors his story—a bitter marriage and confused relationship with his muse.

The result was heartbreaking for Dutt. Alongside the film doing poorly, “there were even reports of audiences booing as soon as he appears on-screen in the film. He was devastated,” said Lajmi.

An unfinished story

The book’s chapter headings, ‘Building of a dream’ and ‘Destruction of a dream’, are well-put and thoughtful. This sums up Dutt’s devotion to climbing the dream ladder—working tirelessly and narrating stories close to the heart. He went all out and didn’t leave anything behind. Reading about it reminds me of what writer Charles Bukowski said, “Find what you love and let it kill you.”

The quotes at the beginning of each chapter act as a great hook and create anticipation for what’s coming next. One such quote, said by Dutt, is, “Director banna tha, director ban gaya; actor banna tha, actor ban gaya; picture achcha banana tha, achche bane. Paisa hai, sab kuch hai, par kuch bhi nahi raha.” (I wanted to become a director, and I became one; I wanted to become an actor, and I became one; I wanted to make good movies, and I did. I have money, I have everything, yet I have nothing.)

This melancholic quote sums up his life—amid the glitz and the glamour, he couldn’t dismiss the essence of his sadness.

Reading about his death raises the question of “what could have been?” When he died so young, many projects he was working on at the time were left unfinished, and his life story was cut short. Hence, the author aptly put together the book’s title, ‘Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story’.

In the end, we see several rare photographs from different phases of his life. From his early days in Calcutta to his final days in Bombay, from movie sets to intimate family photos. In each of these photos, we see a man in transition, a man on a mission, but above all, a sensitive genius who saw the world differently, who mixed commerciality and artistry—leaving behind a huge legacy.

______

Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story

Author: Yasser Usman

Publication: Simon & Schuster

Year: 2021

Pages: 309

21.13°C Kathmandu

21.13°C Kathmandu