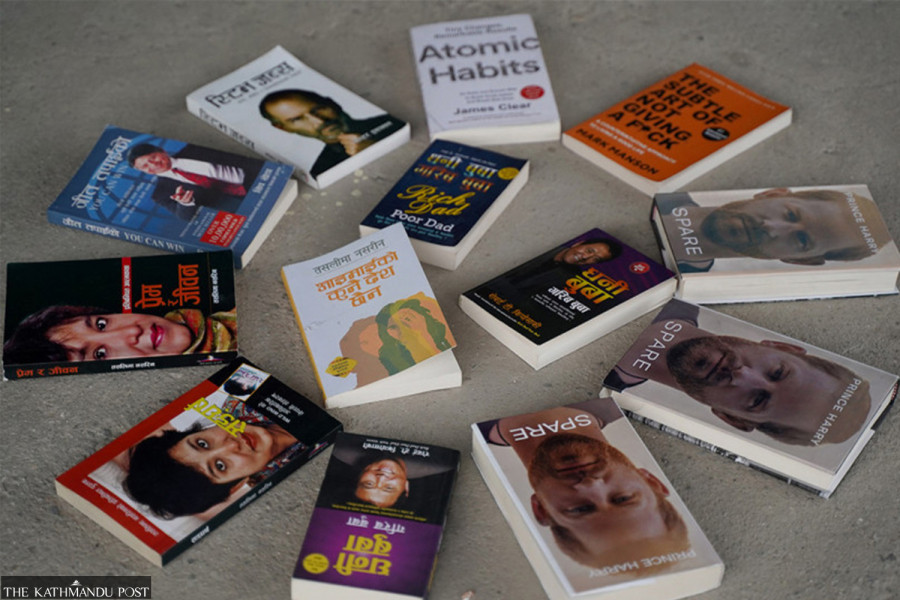

Books

Unauthorised translation and piracy of foreign books thrive in Nepal

The phenomenon has not just hurt creativity but also caused losses to authorised translators and publishers. There is law but implementation remains lax.

Upendra Raj Pandey

Nepal’s book market is no stranger to the popular Bangladeshi-Swedish writer Taslima Nasrin. Almost all of her books have been translated into Nepali, but Nasrin herself says that they are all unauthorised translations. “All books [Nepali translations] are pirated versions,” Nasrin told the Post in a Whatsapp conversation. Nasrin, who is currently in exile in India after facing death threats in Bangladesh following the publication of her novel Lajja (Shame), said that she or her publishers have never allowed anyone the right to translate her books into Nepali. “I don’t know of any such Nepali publishers. No one asked for permission and no one has paid [me] royalty.”

Translating and publishing books without permission from authors or publishers is a punishable crime. But Nepal’s book market is full of such unauthorised translations and prints of books written by the who’s who of the world literature.

Such endeavours haven’t just hurt the authors but also the readers, says Ajit Baral, publisher of the Kathmandu-based Fineprint publication. “These translations are poor,” Baral says. “Tomes with 1200–1300 pages have been trimmed to 200–300 pages. An example is the biography of Bill Clinton.”

Another popular book that has seen unauthorised Nepali translation is the biography of Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson.

“We have no official deal in place for a [Nepali] translation of Steve Jobs,” Peppa Mignone, associate agent of the CAA, the translation authority of the biography, said in an email interview with the Post.

The book’s Nepali translation is published by Panchpokhari Publication House. The translated book identifies the translator thus: “Achyut Koirala, who has a master’s in English literature, is primarily a journalist. He is currently affiliated with Nagarik daily. He keeps a close tab on international history, politics and culture and has written scripts and dialogues for half a dozen Nepali films. He has published over a dozen non-fiction books.”

Koirala, who admits to the unauthorised translation, claims that he hasn’t just translated the book but has also done ‘creative writing’ with it.

‘Rich Dad Poor Dad’, written by Robert Kiyosaki and Sharon Lechter, is among the books that’s perennially on the bestseller list across the world. Upon investigation, the Post found three Nepali translations of the book—all unauthorised. One of them is translated by Dilip Kumar Shrestha and published by the same firm, the Panchpokhari Publication House. Another Nepali iteration of the book is published by Book For All publication and translated by Kopila MD. Yet another Nepali version is translated by one Sudheer Dixit and published by Plata Publication, Kathmandu.

In an email conversation with the Post, Ronson Taylor, who oversees the international rights at The Rich Dad Company, said, “At this point in time, we do not have a relationship with an established publisher in the [Nepali] language market. If there are any Rich Dad Poor Dad books currently for sale in the Nepali market, they are pirated.”

Basanta Thapa, a writer and translator, says that many books are being translated of late to make easy money. “But how would the quality of these unauthorised translations be!” Thapa wonders. “Readers who haven’t read the original wouldn’t know the faults in the translated versions.” Thapa says that any translator worth his salt aims to ‘recreate’ a book and it takes much work to do that.

Taslima’s books are the major victims

Taslima’s memoir Uttal Hawa has been translated into Nepali as ‘Sangharsha’, literally Struggle, and is published by Khoji Publication House. Even though the book in its cover claims that it is an authorised translation from the English version Wild Wind, it is a pirated one. The book is translated by Bikash Basnet and edited by Bhogiraj Chamling. A revised version of the book is edited by Sangeet Srota (Yam Bahadur Chhetri).

The same publication house has also published the Nepali translation of the book’s sequel as ‘Prem ra Jeevan’. Publisher Sushil Chalise says that while he is aware that one needs to receive permission from the author or the publisher to translate a book, his efforts to contact Taslima were unsuccessful. Therefore, he had published the version the translator made available to him. Translator Basnet, too, admits he translated the book without Taslima’s permission. “About a decade back, we didn’t know how to ask for permission,” he said.

Nepal has the Copyright Act (2002) in place. Before it, there was the The Patent, Design and Trade Mark Act, 2022 (1965) that included intellectual property in its 2006 revision. Even the Muluki Ain (Civil Code) of 1910 BS had a provision about copyright. Moreover, it goes without saying that translating somebody else’s work without permission is immoral.

Likewise, Indigo Ink Pvt Ltd has published a Nepali translation of Taslima’s anthology of essays No Country for Women as ‘Aaimai ko Kunai Desh Chhaina’. The book is translated by Krishna Giri and edited by Pramod Pradhan. “I have no idea about the agreement between the publisher and translator,” Pradhan, who is also a children’s book writer, says. “I just copy-edited it upon request.”

Bishnukumar Poudel, publisher of Indigo Ink, however, claims that he is still trying to take translation rights for the book. “We translated the book long ago,” he says. “We are still trying to get translation rights.”

Indigo is also publishing unauthorised translations under its imprints All Book Store Pvt Ltd, Book for All and Plata Publication. It has published two versions of Rich Dad Poor Dad under those shadow imprints. But Plata Publication is not registered in the Company Registrar’s Office.

Pradhan says that many foreign books have had unauthorised translations in Nepali and their quality is poor. Those books are translated not from the original language but from a second or third language, so these translations are bound to have problems, he says. “After I learned that those were unauthorised translations, I have stopped editing them,” Pradhan said.

Indian author Shiv Khera’s You Can Win has been translated into Nepali by Bloomsbury India and has granted the distribution rights to Ekta Books. But the book’s unauthorised translations are also found in the market and they don’t even mention the name of the publisher and translator. What is interesting is they mention that it’d be illegal to republish the book, or an excerpt of it, without the author’s permission.

The Nepali translation of the book, which was poorly written and rife with inaccuracies, had landed the publisher at court. After a complaint was filed at the District Court Kathmandu in 2066BS on the charge that the publisher violated the copyrights and economic rights, the court had issued a verdict on Mangsir 11 that year, charging a fine of Rs10,000, Rs20,000 and Rs30,000 to the defendants Netra Prasad Pokharel, Narayan Prasad Bhusal, and Bhagwati Risal and Bishnu Silwal, respectively.

Baral, the Fineprint publisher, says that international publishers wouldn’t demand much for translation rights given Nepal’s small market, but Nepali publishers do not bother to reach out to them. “Publishers who put out unauthorised translations and sell them at 50 percent discount have troubled publishers like us,” he said.

Fineprint has published authorised translated versions of books such as Leaving Microsoft to Change the World by John Wood, Healed by Manisha Koirala, and Hippie by Paulo Coelho. The publication house is also set to release the Nepali translation of Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari’s bestseller Sapiens. Translated into Nepali by Dinesh Kafle, the book’s translation right was acquired at the cost of USD1300, Baral said. Likewise, the publication acquired the translation rights of Sadhguru’s Inner Engineering at IRS93,000, he added.

Baral says that publication of unauthorised translations is an immoral and illegal work. “This phenomenon not just hampers Nepal’s fledgling book publishing industry but also tarnishes the country’s reputation in the global market,” Baral said.

Thapa, the writer and translator, points out the lack of regulatory mechanisms in the country. “We don’t have an agency that regulates the quality of translations being done,” he says. “Nobody compares the translation with the original. We need a dedicated authority to enhance the quality of translation.” Universities, Nepal Academy and other stakeholders can play a role to uplift the translation sector, he adds.

One’s pain, another’s pleasure

When the author Suketu Mehta was travelling through Mumbai, a young man approached him with a handful of books while his vehicle was stuck in traffic. Brandishing Maximum City, written by none other than Mehta himself, the young man requested the author to buy a copy. Suketu leafed through the book and said, “This is a pirated copy and I’m the author of this book.” The youth wasn’t bothered and replied, “Okay, you can buy it at a discount.”

This anecdote was shared to the Post by Mehta’s friend, the author and professor Amitava Kumar, in an email exchange.

Most of these pirated books are imported into Nepal from India while the retailers of original books are finding themselves increasingly in trouble. “We sell original copies but many readers doubt us as well, given the ubiquity of pirated versions,” says Anjan Shrestha, operator of Education Book House, Jamal.

Ramchandra Timothy, chair of Thapathali-based Ekta Books Pvt Ltd, said that the phenomenon of piracy has tarnished Nepal’s image internationally. “There was a time when Bangladesh would be known as ‘piracy king’,” he said. “Now there's a risk Nepal would take the crown.”

As tax increases, so does piracy

The government decision to impose a 10 percent tax on book imports in fiscal year 2019-20 led to a proliferation of pirated book markets, booksellers say. After the decision, booksellers started to cut back on imports and that led to the entry of a new crop of pirated booksellers, a trader in Kathmandu says. But following widespread backlash, then finance minister Bishnu Paudel struck down the policy.

“After the government’s decision, we stopped importing books for a while,” says Shrestha of Education Books. “The import of books went down for about two years. Then the pirates stepped in to fill the gap. It was about that time that pirated copies of biographies and memoirs of Obamas and Jai Shettys became omnipresent in the market.”

Pirated copies of classics by Roald Dahl and JK Rowling also made an entry in the Nepali market. Then the phenomenon only saw a rise.

Since the customs department does not levy duty on foreign books and also does not care to differentiate between the pirated and original copies, unauthorised books have found a safe haven in Nepali market.

The government doesn’t levy any customs duty on books and newspapers published by foreign publishers abroad. The importers should only pay Rs565 at the customs points. But Nepali publishers have to pay 10 percent tax to import books printed in India.

James Taylor, director of Communications and Freedom to Publish of the International Publishers Association, says that the government, publishers, writers and readers should join hands to control widespread piracy. “The government should realise that book publishing and reading culture contribute to the country’s economy as well,” he said, adding that the government should seize pirated books and close websites that sell pirated ebooks.

Nandan Jha, executive vice chair of Penguin Random House India’s sales, production and business department, says that piracy has emerged as a big challenge for publishers of late and has harmed the authors, publishers, distributors, printers, readers and other stakeholders. “To confront piracy, all the stakeholders should launch a special joint effort,” Jha told the Post in an email exchange.

Piracy has proliferated in the Nepali market to such an extent that the publishers of such books and unauthorised translations keep whatever ISBN numbers they like, often conflicting with other books, and still get off scot free. If scanned or searched on the internet, the ISBN number gives details on the author of the book, what the book is about, and its price, among others.

Bijay Sharma, information officer at TU Library, says, “Keeping ISBN number at one’s will is illegal. If anyone files a complaint, we can punish them.”

By the law

The Muluki Ain-1910 BS had mandated that a publisher take permission of Gorkha Bhasa Prakashini Samiti before publishing any material. The Copyrights Act came into effect in 2022 BS and was amended in 2054 BS. In 2059 BS, a new Act was promulgated and it is still effective now. Authorities are currently working to amend the Act to give the registrar’s office more autonomy regarding copyright.

According to the 2059 BS Act, copyright violations are considered government cases. In such cases, plaintiffs should file a complaint with the police. The Act’s clause 25 has various conditions that amount to violation of copyright. The Act’s subclause A says that if a publisher produces or copies material in writing or sound and sells or distributes it, it amounts to violation of copyright.

Likewise, the Act’s clause 26 prevents selling of unauthorised material. The clause restricts the ‘importation of copies of work or sound recording, either made in a foreign country or sourced otherwise, into Nepal for business purpose shall not be permitted if preparation of such copies would be considered illegal if they were prepared in Nepal.’

If anyone infringes upon protected rights, they are liable to punishment but the provision’s implementation remains lax.

The law gives the authority to district court to take legal action against copyright violators.

Advocate Parshuram Koirala says that if the government becomes more proactive, it can punish violators on the basis of the 2059 BS Act and thereby control the phenomenon of intellectual theft and copyright violations. “Creation is a crucial part of humanity’s benefit,” he says. “If intellectual property is not protected effectively, then there’d be no inspiration to create something.”

Bal Bahadur Mukhiya, a professor at Nepal Law Campus, suggests the inclusion of rules about digital piracy in law, and also the clauses of various related international treaties and agreements that Nepal is part of.

“In the US, a teacher or professor should pay a certain revenue even to photocopy a chapter of some text for teaching purposes,” Mukhiya says. “But in Nepal, those who photocopy an entire book and sell it go scot free.”

(This report is prepared in collaboration with the Centre for Investigative Journalism, Nepal.)

15.87°C Kathmandu

15.87°C Kathmandu