Books

Life, liberty, and being pursued by trauma

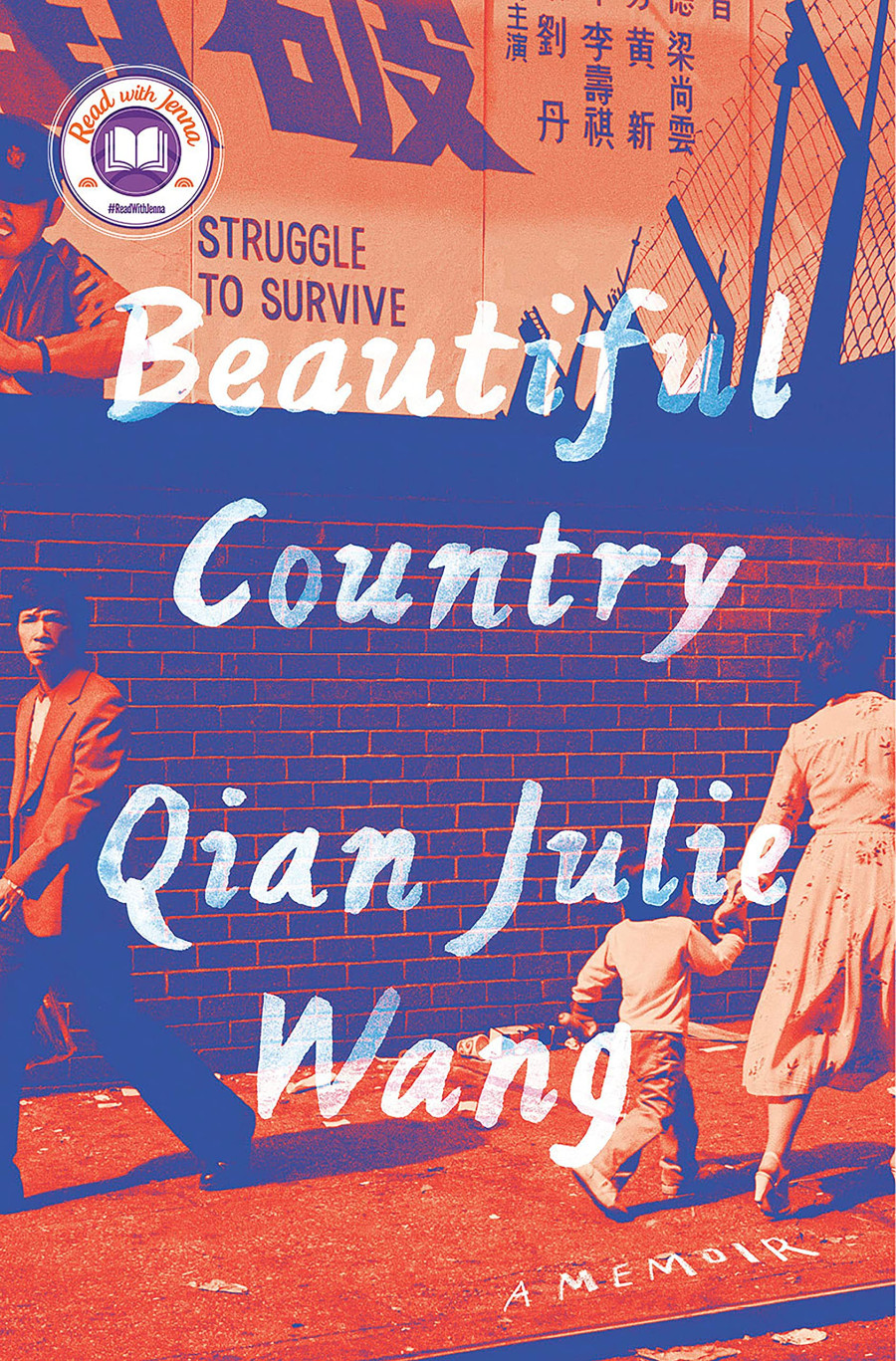

Qian Julie Wang’s memoir ‘Beautiful Country’ is all that a girl’s childhood should not be.

Richa Bhattarai

There exists a rare breed of people who were sent to this earth to write. They send you a work email, and it reads like a love letter. They copy-edit an advertisement and tears wander down your cheeks. And when they write a book, it is an unforgettable memoir like Qian Julie Wang’s ‘Beautiful Country.’ Even her preface is gorgeous:

“I dream of a day when being recognized as a human requires no luck–when it is a right, not a privilege. And I dream of a day when each and every one of us will have no reason to fear stepping out of the shadows.”

And yet, gorgeous is a word I would hesitate to use for her memoir. It is inordinately beautiful, yes, but it is a beauty born out of a fellow human being’s deepest trauma. There is so much trauma within these pages that each one needs a trigger warning: racism, xenophobia, violence, sexual harassment, gaslighting, microaggression, poverty, hunger, mental illness, fear, culture shock, parental neglect, animal abuse.

Qian’s life did not begin this way. She talks of a relatively happy childhood, a single child of professor parents, cocooned in the love of her grandparents. There are tables groaning with food, matching dresses with her mother, and joyful dances with her father. But when Qian is five, her Ba Ba goes to America–Mei Guo, literally ‘beautiful country.’ “Out of nowhere, there was a frog in my throat and a rock in my heart,” says Qian, and no writer has ever described the angst of separation from a loved one quite so well for me.

Two years later, Qian and her Ma Ma follow him into the land of supposedly infinite opportunities. But for this family, there is no opportunity. There is only terrible, terrible loss–a loss of prosperity and resources, confidence and self-esteem, sanity, and joy. Perhaps worst of all for them, the loss of ‘face.’

Qian writes of these five years as an undocumented family in the United States. Her formative years, when she should have been a child worrying about nothing except missing pencils and cartoon shows, but instead, “I ascended to adulthood at cruising altitude,” she shares ruefully. While there are numerous accounts similar to this, Qian’s memoir is unique because it is actually through the eyes and mind of a child. Embedding that duality of innocence and precociousness is difficult, yet Qian does it perfectly. Readers are able to exist as little Qian and experience her anxieties and preoccupations, her humiliation and anguish.

The memoir is not all sorrow, though. It is kept quirky, lively, and relatable through Qian’s childlike observations. She paints her landlady this way, “For some reason, our landlady liked to hide in the closet while everyone ate.” This line immediately conjures up a giggle. When Qian describes eating a slice of pizza, she speaks for so many of us, “Eating American food was like gulping down giant and instantly gratifying bubbles of air.” When she gets to eat white-rice congee for sixty cents, her words send a sigh of satisfaction through every reader, “I had no idea that all this time we could buy heaven for so little.” Eating at a McDonalds, Qian ruminates, “Happiness cost almost twice our weekly food budget.”

Qian writes of her school where she is one of the only two students in class opting for a free lunch, of her mother’s workplace that she joins to earn a cent per shirt, of her father’s gradual descent into a stone-hearted man, of the family’s desperate attempts to eat, sleep, just exist in this country with the threat of deportation never far from their racing hearts. All through her revelations, the writer seems to be exceptionally candid, never once attempting to be the perfect protagonist so typical in a memoir. She has portrayed the darkest ways a parent can be, and it is disconcerting and frightening. Some of her recounts are so blunt and deprecating that the reader needs to turn their eyes away for a moment, unable to deal with the naked honesty. There is a constant lump in the throat, imagining all that the three endure.

In the end, this intimate memoir is not only about Qian, or her family, or even the horrifying experiences of undocumented people in the United States. It is a tribute to everyone who has been denied their rights and identities–from a refugee living in a camp in Turkey to a teenager in Nepal denied citizenship. What use, the memoir seems to be musing, are documents that do not identify the most vulnerable as a human being?

While Qian’s moving style has been much celebrated, critics are dissatisfied by the lack of elucidation on why Qian’s father left China and refused to go back even after extreme duress; or how Qian and her mother later escaped. The memoir only describes a few years of childhood, critics have complained, and even that is like a disassociated group of incidents. But even though we have a right to be dissatisfied with a book, I do not think the writer owes us anything. She bared her soul in ways she saw fit, and perhaps it was cathartic for her (or maybe even more traumatic), but as readers, we really cannot demand that someone writing about herself give us more than she can or wants to.

My feelings of disquiet actually arose from acts of cruelty and pettiness Qian has described–desecrating someone’s coffee cup, rinsing their toothbrush in the toilet, abusing a cat, spitting at a parent. It is evil and, at least in one instance, completely unwarranted. But is it the hardships and dehumanisation that turn a person into their worst self? And then again, who are we to take the moral high ground?

Qian’s descriptions of almost all people are immediately unkind and almost repetitive–‘the lady with the fake face’, ‘squat lady with a meat pie for a face’, ‘fat man’, ‘a lady whose skin reminded me of a dumpling wrapper pulled taut’, ‘fat and balding’. All true descriptions, no doubt, but also perhaps exacerbated by Qian’s unusual childhood. “Ma ma was meaner,” Qian observes as they begin their life in the US. Who wouldn’t be when plucked from the life of a published professor to a seamstress at a sweatshop?

Also, Qian is ruthless in her own portrayal, seeming so sly and unlikable until you remember that she is just a little girl trying to protect herself the best she can, among the ugliness of this beautiful country. Her moments of wonder, amazement and gratefulness display the soul of the child she could actually have been.

Talking of her Ba Ba, Qian says, “He had a way of weaving little words into one giant poetic blanket.” So do you, Qian, and that blanket you have woven is one-of-a-kind.

—————————————————————

Beautiful Country: A Memoir

Author: Qian Julie Wang

Publication: Doubleday

Price: INR 697

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu