Books

Autobiography of a former chief justice

In this extensive book, Gopal Parajuli shares his personal and professional journey.

Madan Kumar Bhattarai

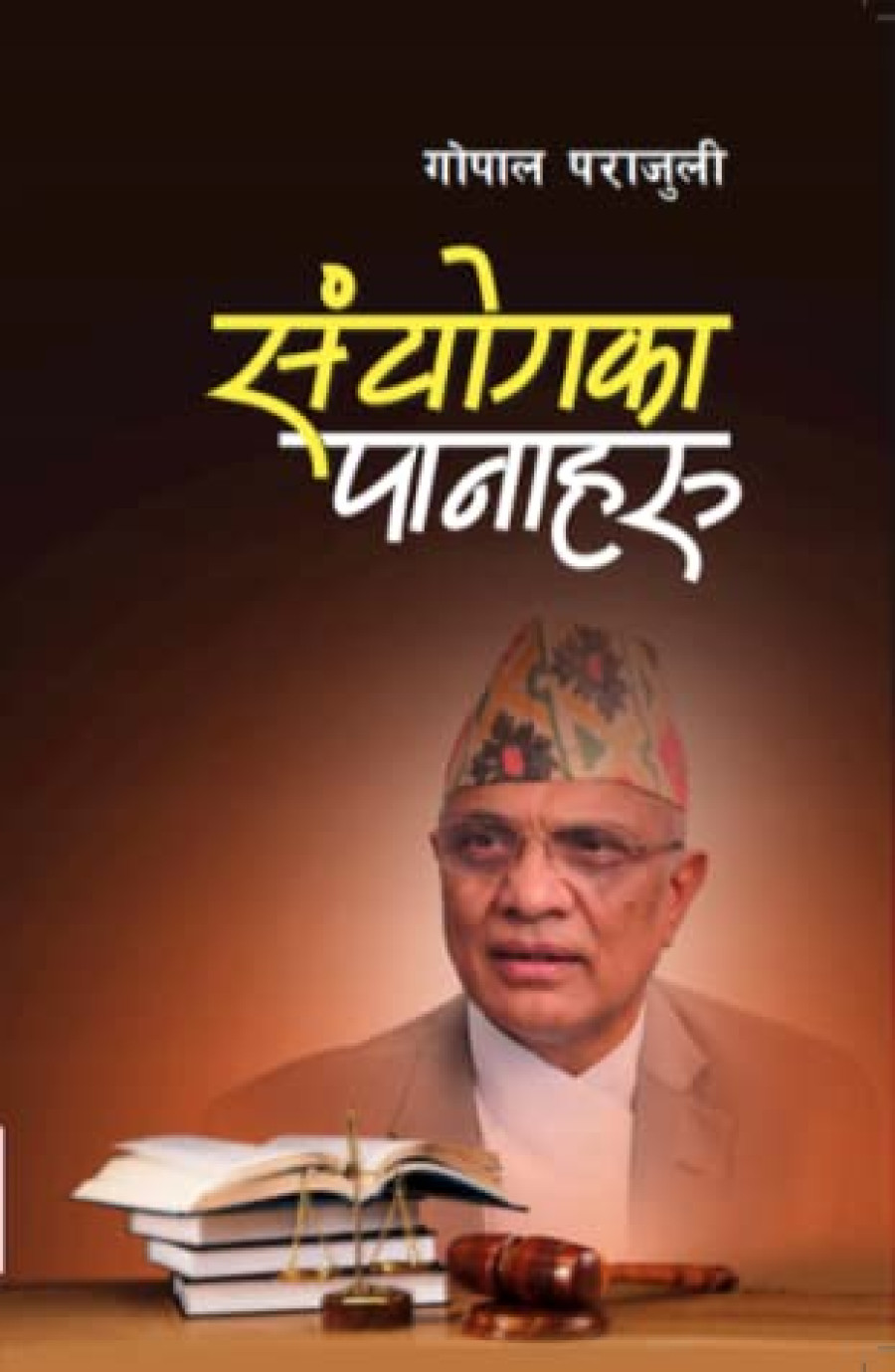

Gopal Parajuli, Nepal’s 27th chief justice, has brought out a very comprehensive autobiography narrating his experience with remarkable clarity and flow. The book is titled ‘Sanyogka Paanaaharu (Aatmakathaa)’, and it is divided into five chapters and four appendices, the last of which has a good collection of photographs.

Besides words of greetings from another former Chief Justice Om Prakash Mishra, the book includes a longer preface by Yubraj Sangroula, who is the former attorney general. It also has quite a long note by Chandra Prakash Siwakoti on behalf of publishers.

In his foreword, Parajuli shares that he hesitated for a long time on whether he should write his autobiography. He did write the first section of the book on the day of his resignation itself and didn’t take very long to complete the book. He, however, thought it prudent to bring the matter to the correct perspective by sharing his own thoughts on what he calls a ceaseless campaign against him. In analysing trials and tribulations he confronted during his tumultuous life mixed with a saga of success and tragedy, Parajuli finds faults with deification and vilification, both of which are prevalent in our society. He shares pragmatic thinking that humans, though the most conscious of the living beings, have dozens of good and bad attributes and can never be perfect.

Both Mishra and Parajuli hail from the same district. They joined the Supreme Court on the same day and reached the highest judicial position, with the former staying as chief justice for some months and Parajuli tendering his resignation after what he calls a sustained and spirited campaign launched by a group of people with vested interests. Mishra assesses Parajuli as a versatile person endowed with wonderful judicial acumen and the capacity to draft judgments in a simple and lucid manner.

Calling the new book a tell-tale work to highlight the actual situation of Nepal's judiciary, Sangroula opines that the slander launched against Parajuli was not merely a personal attack but a systematic plan to ultimately break the very fabric of the judiciary. He also laments the dearth of books by chief justices, justices and other judicial stalwarts in Nepal in comparison with India, and Western countries where there is a plethora of such publications and a culture of sharing of experiences through books and lectures at universities. From what I know, only four chief justices, which includes Parajuli, Nayan Bahadur Khatri, Meen Bahadur Rayamajhee and Sushila Karki, have taken interest in writing memoirs. Ironically, Parajuli has directly or indirectly attacked four chief justices in terms of their track records.

Siwakoti, an advocate himself, traces the history of Nepal's judiciary that has so far been served by 29 chief justices. He also points out late former Chief Justices Hari Prasad Pradhan and Bishwa Nath Upadhyaya for their wonderful contributions in upholding the dignity of the highest court of the land through their dedicated and impartial delivery of justice. Unfortunately, both of them didn’t write anything that could have shed light on the history and perspectives of the judiciary during the critical periods they served.

In the first chapter of the book, which has twenty sections, Parajuli writes about his ancestors, parents, childhood and the struggle he had to face after migrating to Tarai for better livelihood. He deals at length about his entry into Law College in Kathmandu after studying in various parts of Nepal and India, his forays into student politics, both before and after the National Referendum called by King Birendra in 1979. He also writes of his close association with the top Nepali Congress leaders including prime ministers.

The writer has also mentioned some very personal aspects of his life in the book. Parajuli writes about his near-fatal motorbike accident. Readers learn that Parajuli’s pillion rider died on the spot while he battled for his life for thirteen days at a hospital’s intensive care unit. A section is dedicated to Parajuli’s traumatic personal life. He divorced his first wife, and his second wife succumbed to blood cancer. His third wife and one of his sons died in a vehicle accident, and Parajuli, who was driving the car, left him badly injured.

The second chapter with eleven sections relates to the writer's induction into the judiciary as an Appellate Court judge. He gave judgements on some high-profile cases that attracted both positive and negative reactions. In this connection, he accuses one former chief justice of harbouring an allegedly discriminatory attitude towards him in various manifestations including prevention of his timely appointment as chief judge of the Appellate Court and even his ascension to the Supreme Court.

Chapter three, which is divided into nine sections, is the longest chapter and constitutes the crux of the book as it depicts the many trials and tribulations the writer faced during his tumultuous tenure in the judicial service leading up to his resignation, an act that was sparked by a letter issued by Nripa Dhoj Niraula, secretary of the judicial council, terminating the service of the fourth highest office holder of the land. In the fourth chapter, going both within and beyond his areas of entrusted duty, the author has talked of various subjects like national interest, poverty, farming sector, do's and don'ts of judiciary and journalism, etc.

The fifth and concluding chapter is more introspective and Parajuli has not hesitated to cite his own weaknesses.

Despite some overlapping issues, the book, in a nutshell, is a solid addition that can be linked with autobiography and Nepali aspects of jurisprudence and juridical science. I congratulate the author for his important contributions.

Sanyogka Paanaaharu (Aatmakathaa)

Gopal Parajuli

Publication: Pairabi Book House

Pages: 514

Price: Rs 825

22.11°C Kathmandu

22.11°C Kathmandu