Books

Keeping intact silences and reading between the lines

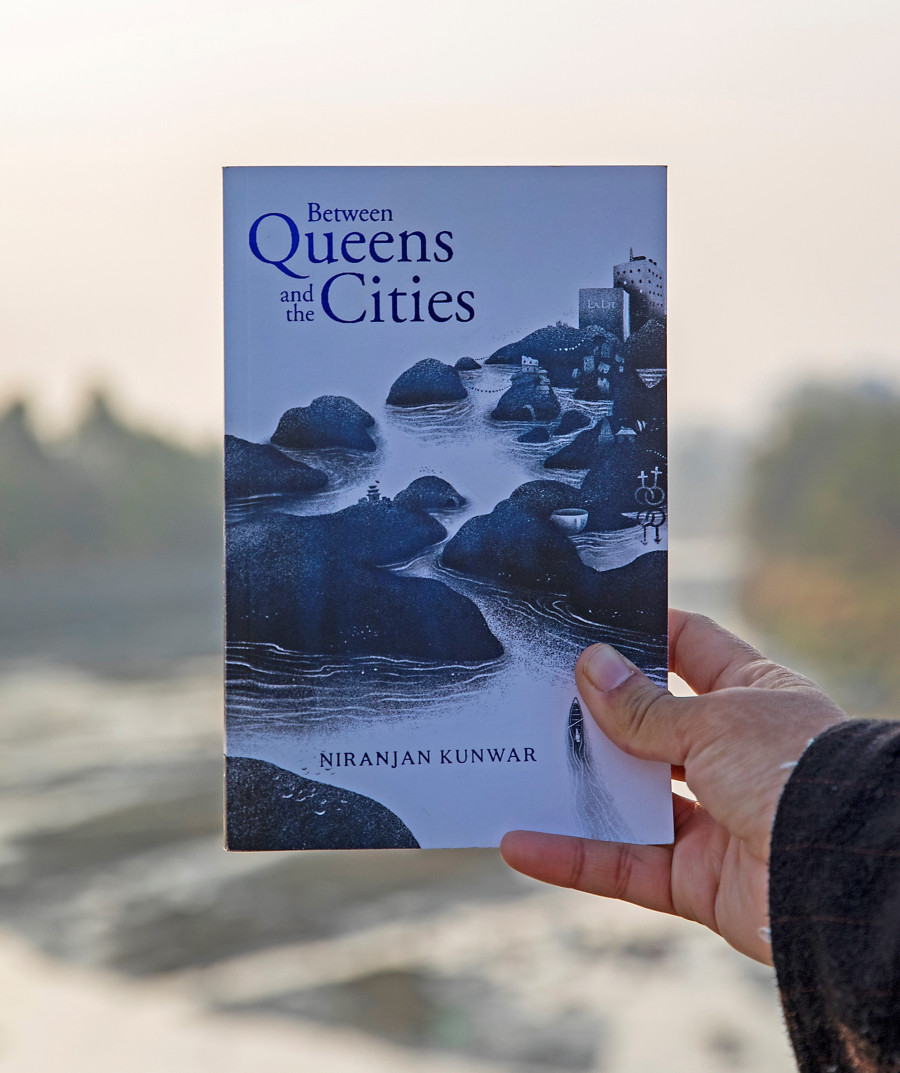

Niranjan Kunwar’s accounts of a queer man navigating through his life in ‘Between Queens and the Cities’ is not an uncommon story, but it is an urbane and hopeful recollection.

Srizu Bajracharya

When we are unable to tell our truth, we feel choked. That then creates our boundaries and we are left with nothing but to escape ourselves, continually and exhaustingly. Writer and educator Niranjan Kunwar’s memoir, titled Between Queens and the Cities, in many ways is a testament to such a struggle but in more ways it is an ordinary story about a man uncertain of life and what he wants.

The memoir starts right away with Kunwar telling readers that he is gay, and when he was young, at 18, he felt like he was alone, the only gay person in Kathmandu. In 1999, young Kunwar was uncertain of his life, and cynical of the Nepali society. He was sure that it would not accept his truth and so, he leaves behind this reality to explore himself both as a gay man and a teenager hopeful about life.

In New York, Kunwar finds himself unrestrained, able to accept who he is and others who take an interest in his life. He is wary but ready to engage with the world. There, in Queens, he is determined to carve a space for himself, a career and a life away from a Nepal where he could not see himself living openly. Kunwar instantly falls in love with New York, its diversity and accessibility. He also finds himself entwined with the art and openness of the city. And for over a decade, he works hard and carefully to make a permanent life in the foreign land.

As the reader engages with the book, we see Kunwar’s day to day mundane regularity—reflective of the lives of many migrating youth: struggling with the hassles of paperwork, finding a proper place to live and ensuring that you don’t have to go back home soon. And we also see Kunwar’s journey as a writer—the way he reflects over situations, his emotions, with the way he romantically sees travelling, and the emphasis he gives to reading and writing.

And in all this, we also see his privilege: the society around him is more positive, more full of possibilities, than it is for most queer people in Nepal but nevertheless, Kunwar’s story is not without dark days.

His perception of the Nepali society and his family has him running away from who he is. We see Kunwar ready to tell a stranger who he is but holding back to confront his family for half of the book. This takes a psychological toll on him and as he feels suffocated, his relationship with his parents suffers and becomes complicated. Kunwar’s complex relationship with his father however is not tied deeply with his sexuality but to a generational ideological difference, that of a conservative man and a liberal, unmethodical young man.

But his relationship with his parents reflects what most Nepali families share, where families are not comfortable discussing their emotions. Parents nonchalantly disregard uncomfortable confrontations, even moments of one’s emotional outburst. One of the most striking lines in the book is by Kunwar’s mother, who when hearing her son is gay, says: “I don’t like these things”, denying her son his sexuality.

His truth stirs the family, but Kunwar feels liberated and we see him grow stronger, even his language in the book thereafter becomes more confident. Later, having revealed himself, he is finally also able to think of returning home and pursuing his interests in writing, education and art.

In the book, Kunwar also summarises queer history and reflects on Nepal’s political history, how the country has changed and how the youth of the country are more aware socially and politically. He looks at Nepali society with disdain, and it is apparent that his contempt is attached to how the society alienates the experiences of the queer.

But one thing that is abrupt in the overall narrative is the writer speaking about other inspiring queer people, like Rukshana Kapali, Bhakti Shah, and Esan Regmi, in the chapter ‘No One Sings our Songs’. Throughout the book we feel a connection with the writer and the isolation he, and other queer people, feel in Nepali society, but the suddenness with which his memoir shifts focus from his personal life to the lives of individuals who seem to have little connection to his life story makes it feel like we’re reading a completely separate piece of text.

In regards to his writing, Kunwar uses short sentences and takes readers swiftly into his story with his simple language. For transitions, he is also very descriptive of the seasons and the weather and he is able to create beautiful imagery of the cities that shape him. And Ubahang Nembang’s illustrations further fosters that imagination of Kunwar navigating to find himself between cities. And the title itself hints to how Kunwar feels, almost asking readers where his place is in this world.

But it also seems like Kunwar stops short of telling the readers more about himself, laying his emotions bare. We see Kunwar looking for intimacy and companionship in different relationships, but he doesn’t reveal much about crucial events of his life, like his fight with his brother’s wife, and in moments when he is going from places to places, what he is thinking. Or, when he is sitting down to write, he doesn’t reveal the subtleties of what makes him write. We just come to see that he is a writer.

Despite this, readers will find themselves relating to his wanderings because Kunwar works with an intangible feeling everyone can relate to in their pursuit of life. He is as confused as anyone trying to figure out their life.

He also throws a lot of names, which are difficult to remember as his characters are not fleshed out well. In some places, Kunwar speaks about his past writings without much background. This includes his column for TNM, a men’s magazine, as Charlie Chaulagain, and an article, titled Silence and Shame, about his boarding school experience in Himal Southasian. He mentions these pieces, tells how he feels about them but doesn’t really delve into experiences, as though expecting readers to have already read them.

But inside the book, in brief intros of his six parts and in italic passages in between the humdrums of his life’s exploring, he expresses his emotions more deeply where readers will be more able to see through Kunwar’s unrest. One record reads, “No one counts our blessings. No one blesses us. We exist outside religion, outside society and culture. We are too Western or too wild…”.

Kunwar purposely takes on a narrative that does not delve too deep in his thoughts and feelings. His recollections show his reaction, his adventure and pursuits. And sometimes Kunwar takes readers from one event to another aimlessly—while readers await for these events to culminate into something, nothing happens.

But that perhaps is why Kunwar’s book is odd and interesting in its own way. His book is not about overcoming the odds, like how most memoirs are or are thought to be like. It's not resolute with its direction as Kunwar himself is exploring life. He finds joy in talking about his friends and their endeavours. He shows how he feels inspired with them around and it is they who have comforted him here at home. He has fallen in and out of love, and still is hopeful about love and he has matured with years, and that is his story.

And towards the end there is no reconciliation to his familial relationship, and he is no longer looking for acceptance. Rather, what we see is an assured Kunwar who believes he can now manage most things in life. “Sitting on this chair in my study and writing, I am relaxed as the sunsets,” he writes. His unfinished ending is more about him becoming calmer and happy with himself.

Oddly, that is all what we all want from our life, to be happy with ourselves. Kunwar’s book isn’t exactly what many thought a first queer memoir would be like, it is justly his story and that is why it confronts and challenges many notions society has of the queer. And that is why it is important. But it will be relatable to everyone.

Still the key to reading this book is to read between the lines and see the unexplained silences for what they are. Kunwar has bravely shared bits and pieces of his life, and will certainly make people more curious about him.

———————————————————

Between Queens and the Cities

Author: Niranjan Kunwar

Publication: Fine Print

Price: Rs 695

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu