Books

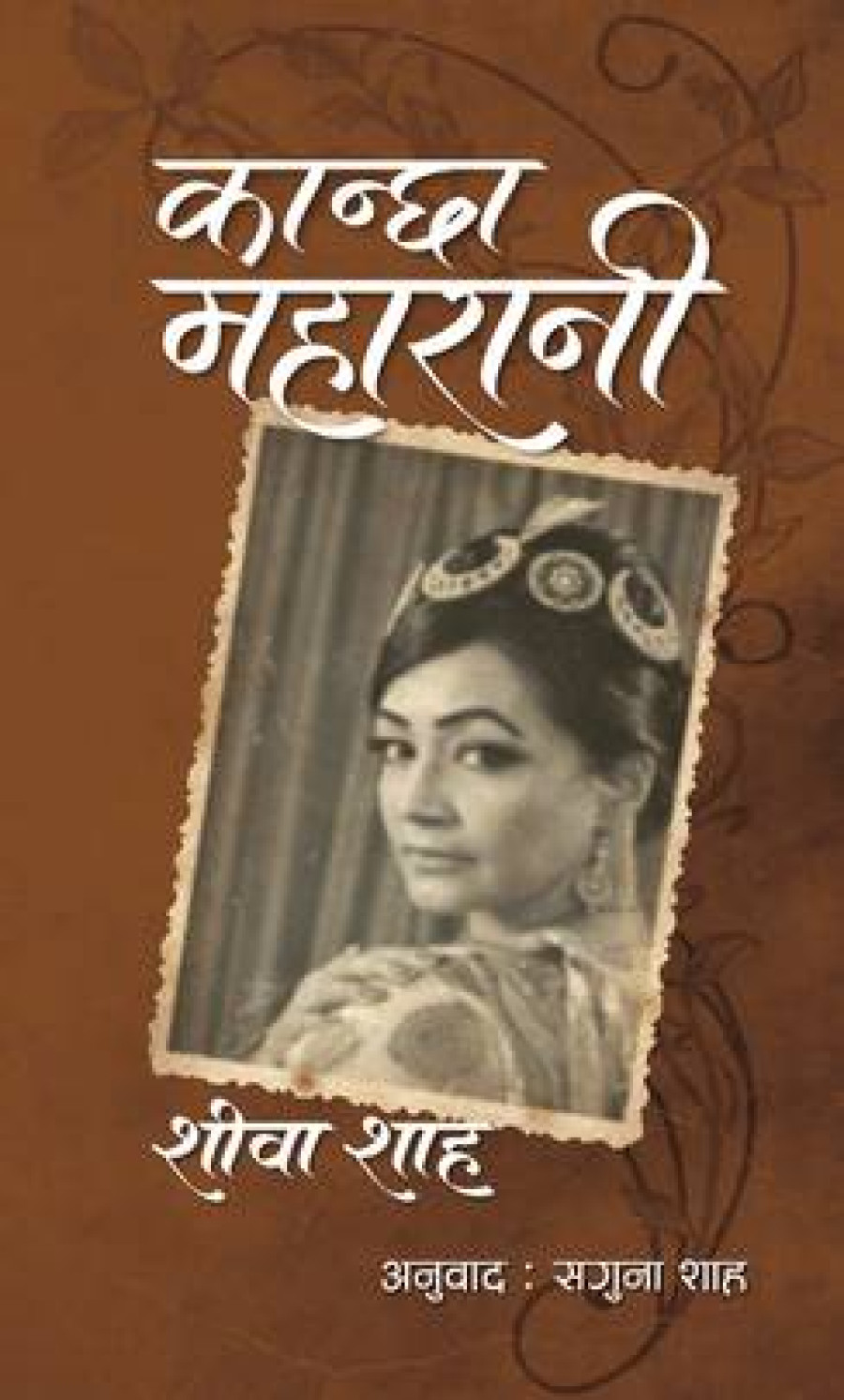

Kanchha Maharani: Gained in translation

Saguna Shah’s elegant translation of The Other Queen, written by Sheeba Shah, not only renders the novel an authentic quality but also makes the otherwise jittery read of the original text a pleasant one.

Bibek Adhikari

After reading Sheeba Shah’s The Other Queen, or Kanchha Maharani (as translated by Saguna Shah), one is left wondering if the glittering world of the Royals is only a public façade masking their pitiable private lives. Readers raise their eyebrows, scratch their heads, mutter a meaningless ‘tut, tut’ at times, only to be disgusted in the end by the “ruinous night of delirious carnage” of 1846 that changed the course of history.

The 378 pages-long novel retells the account of the pre-Rana regime in Nepal, one that is heavy with endless jealousy and scheming, not to mention the widespread ploys employed for position and power, or in this case, the erotic desires of a forlorn queen, Rajya Lakshmi aka Kanchha Maharani. This desire more than anything else leads to the Kot Massacre and the subsequent rise of the Rana Regime, which not only disrupted Nepal’s socio-economic conditions but also dragged the country down into an abyss.

Readers get to reimagine history from a woman’s perspective. They get to see the world of the Durbar and the Royals through the eyes of Queen Rajendra Lakshmi, the neglected wife of King Rajendra Bikram Shah. Her clandestine liaison with a mid-rank army officer, Gagan Singh Basnyat, as schemed by Jung Bahadur Kunwar, is the pivotal plot point. The entire work—not to mention the fate of the nation—stems from this affair.

Another interesting aspect of the translation is how the real is well-blended with the fictional. Historical figures like Rajendra Lakshmi, Jung Bahadur, and Henry Lawrence co-exist with fictional characters like Tara, Batuli, and Bubu Aama. The subplots, especially the story of Rajendra Lakshmi’s changing relationship with her maid, Batuli, gives the novel its flesh and blood. These events help readers to step into the “fictive dream,” without doubting if what they are reading is a true account or a figment of the writer’s imagination.

The novel begins with a contemplative prologue, where the unloved queen is lamenting on her fate, but it’s unsure who she is mourning for. Is it for her husband, her lover, or her nation? One cannot be certain in a first reading. Also, all her philosophical conundrums, especially the ones that could not be presented later in the narrative, are hurled on the first three pages, making the opening of the novel a weak one.

Writing a prologue is effective when there’s a piece of information that the writer must convey from the first page, something that cannot be possibly included afterwards. The prologue in Kanchha Maharani, suffice to say, can be safely skipped—and yet nothing is lost. Sometimes ditching an unnecessarily contemplative prologue is the best thing to do in writing a novel.

The same applies to the epilogue—an excessively mawkish poetry-like construction—a mere pseudo-philosophical and seemingly sentimental afterthought, which adds nothing to the narrative on a larger scale.

The writer’s habit of beginning many chapters in a distinctly similar fashion can be one of her idiosyncrasies. In the incipit of many chapters that follow we see the unloved, unpopular, unappreciated queen grieving for her loss, brooding over what went wrong, and at times, wallowing in deepest despair. Although engaging in the beginning, the charm of this incipit starts to wear off, giving the chapters a monotonous feel.

Things like what makes a chapter compelling, how to begin or end every chapter, and what elements of craft to include should come as second nature to seasoned writers. Starting a chapter with action is more riveting than describing the protagonist’s morbid thoughts. The beginning of a chapter is, what I feel, not the safest place to start a philosophical debate on ethics, skepticism, and existentialism, unless one is Milan Kundera and can get away with it.

Strangely enough, we do not feel the monotony seeping into our minds when we are reading the novel in translation. Saguna Shah’s elegant translation not only renders the novel an authentic quality but also makes the otherwise jittery read of the original text a pleasant one. In a way, the translator has weeded out all the pre-existing problems in the English version and given the book an “edited” look.

One thing that might bewilder the “serious” readers of fiction—or even the beginning writers who are grappling with the basics of fiction writing—is the author’s use of the unconventional first-person omniscient viewpoint. Even though the story is told from the perspective of Queen Rajendra Lakshmi, she knows everything that’s going around. She knows what Jung Bahadur is thinking, what Sahibzada Surendra is doing in his chamber, and what the elder queen Samrajya Lakshmi Devi is planning. The narrator is a god-like figure, all-knowing, all-seeing, which is both bewildering and intriguing.

The weakest thing about the English novel is the lack of a second editorial look. Commas are used haphazardly, single quotes are exploited in a sorry state, and the occasional typos punctuate the joy of reading. The scenes change with no visible scene breaks, thus giving the narrative a fraudulent stream-of-consciousness-like quality. Phrases from the Nepali language are often used with no further explanation, and sometimes the italics also go missing. The Nepali translation has done an excellent job of getting rid of such quibbles related to grammar and punctuation.

Although it is Sheeba Shah’s fourth novel, it’s sad to see how she fails to have a strong grip over the basic elements of fiction writing: characters, plot, scenes, viewpoints, and the sentence-level craft that could have made each sentence an absolute joy to read. To quote Nabokov, “A writer should have the precision of a poet and an imagination of a scientist,” and failing to possess both qualities results in the production of an unenjoyable work. Many of the Nepali writers writing in the English language suffer from this syndrome.

Be that as it may, these flaws in the English novel, no matter how clumsy and vexatious, can be easily rooted out by a skilled book editor in the second edition, making the novel a top-notch work of art. As of now, both the editor and the writer are to partially blame; only the translator deserves to be applauded for her meticulous translation and copy-editing skills.

To put it briefly, Kanchha Maharani gives the readers a much-needed female perspective to a male-dominated history (or ‘his-story’). This attempt, similar to new historicism, is a praiseworthy endeavor in Nepali literature. Not only does it glorify royalty from a peculiar angle but also gives agency to the anti-heroine, Rajendra Lakshmi, thereby dismantling the gendered meta-narrative and making the book a sound example of a feminist narrative. Anyone interested in reading a counter-narrative that explicates the life and times of Rajendra Lakshmi should unquestionably pick up the Nepali translation of The Other Queen.

Book: Kanchha Maharani

Author: Sheeba Shah

Translator: Saguna Shah

Genre: Historical Fiction

Publisher: Shangri-la Books

Price: Rs. 450

11.84°C Kathmandu

11.84°C Kathmandu