Books

A poet whose words still matter

‘If the language survives, so will the civilisation.’

Srizu Bajracharya

Prime Minister Juddha Shumsher banned any use of Nepal Bhasa for business or literary purpose between 1932 to 1945. Shumsher even sanctioned admonitions and fines—some were sent to prison and others forced into exile. This provoked a group of Newar litterateurs to defy government policy—planting a seed for a literature renaissance of their native tongue.

It was then the phrase once used by Mahakabi Siddhidas Mahaju, “Bhasa mwa sa jaati mwai” (“if the language survives, so will the civilisation”) became a mantra for the language movement, and has been a staple slogan for the language rights advocates.

Mahaju, however, wasn’t a political person during his lifetime. He was a poet, essayist and linguist. He often shared his verses in private—with family and friends. But during the Rana regime, the era in which he lived, even that was a dangerous pursuit, says Sharad Kasa, librarian at Asa Saphu Guthi, a public library of ancient Nepali manuscripts. Many writers were also imprisoned during the time, including Yogbir Singh Kansakar, one of Mahaju’s friends.

But a private approach to his literary works led its immortality. Throughout his life, Mahaju steadfastly distributed copies of his poetry among friends, therefore his work survived a time where in literary works were destroyed. His surviving work is still being celebrated within the Newar community—on September 12, Nepal Academy organised an event marking the anniversary of Mahaju’s birth, where contemporary Nepal Bhasa litterateurs recited his poems and celebrated his contributions.

In 1996, following many political transitions, the government of Nepal set up a taskforce to address the indigenous issues in Nepal. It identified a total of 61 different ethnicities as indigenous groups of Nepal, and defined janajatis as “a community having its own mother tongue and traditional culture.”

The relevance of Mahaju’s remarks regarding language became a canon for more than just the Newar community, but for all indigenous nationalities.

“Even in the recent Gorkhaland protest in Darjeeling, where Nepalis fought for their identity, to include Nepali language in schools, they were affirming the same as what Mahaju had said years earlier—if there is no language, there is no identity,” says Kasa.

Although Mahaju is regarded as one of the four great proponents of Nepal Bhasa, along with Nisthananda Bajracharya, Yogbir Singh Kansakar and Jagat Sundar Malla, he had a humble beginning—in life and literature. At 16-years-old, when he came back from Calcutta where he engaged in menial work to survive, he returned with Hindi newspapers and books. He also learned about bookbinding and started penning his own works.

Mahaju was born into a working-class family, and struggled for economic stability for the rest of his life. “He managed to write with the knowledge he had, and kept building on his understanding through his peers,” says Laxmi Mali, chief of mother language literature at Nepal Academy. “For him, his difficult life was his inspiration.”

The poet’s mother passed away when he was still a child and when his father later died, Mahaju was forced into the bread-winning role of the family. Despite the fact that he wanted to focus on writing and publishing his works, Mahaju also had a clothing business for a brief period. The business failed because his passion lied in poetry.

He was one of the first Nepali writers to create fictional worlds and characters to tell stories. In 1910, he published Shiva Vilas Bakhan—in which the main character awakens to understanding why it’s important to expand one’s knowledge and keep sharing it with near and dear ones. It’s as though Mahaju was spurring readers to oppose the Rana rulers’ authority, and to educate themselves.

More than any other writers of his time, Mahaju has altogether written 44 books. He was given the title of ‘Mahakabi’, or ‘Great Poet’, for translating Sanskrit epic Ramayana to Nepal Bhasa as Siddhi Ramayana—it is considered one of his greatest contributions to Nepal Bhasa literature. Mahaju’s works therefore are compared with Adikabi Bhanu Bhakta Acharya, who translated the same piece to Nepali.

The Mahakabi is also recognised as a progressivist because he endorsed equal education and equal rights, on top of his language advocacy.

“He was quite progressive for his time,” says Mali. “He advocated for equal treatment of sons and daughters; and that people shouldn’t be left poor because they wouldn’t be able to grow intellectually,” says Mali. Mahaju also urged that if girls were to be given dowry for marriage, they should be presented with productive items to help them generate income.

When he was working with fellow writer Yogbir Singh Kansakar, as part of his clothing business, Mahaju once again found himself immersed in writing and sharing his poems. Kansakar organised private poetry sessions in his shop, where poets—such as Chakrapani Chalise, Lekhnath Poudyal and Baburaram Acharya—recited and discussed their work with the idea to encourage creativity and critical analysis. They believed without an audience, poets lose the significance of their creation.

.jpg)

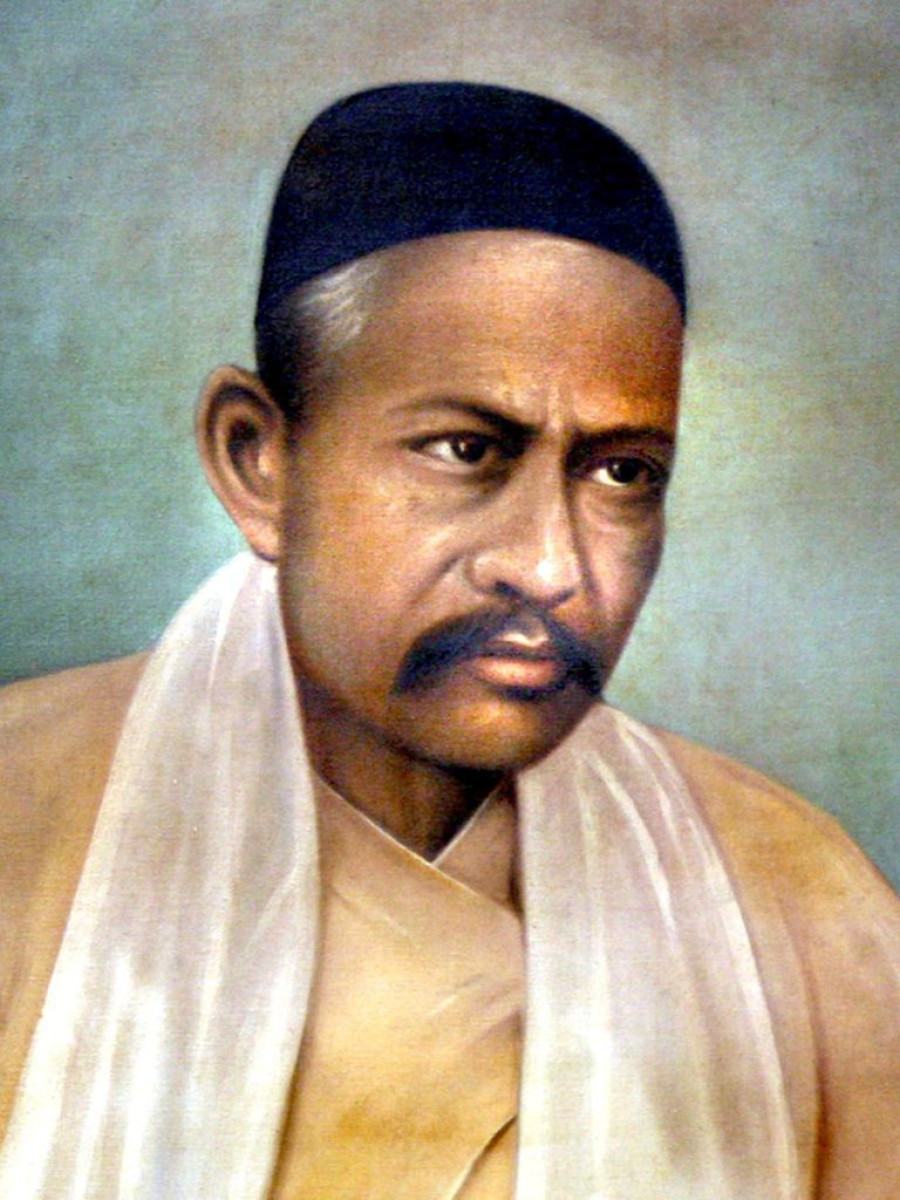

Later, he travelled to Birgunj as a trader. There, he wrote the renowned Sajjan Hridayabharan (pictured), a collection of moral poems, while bed-ridden with malaria. Upon returning, he started working at Bhu Dharananda Vaidya’s Wasa Chhe, an ayurvedic medicine shop near Durbar High School, as a medicine miller. But, even there, according to librarian Kasa, Mahaju wrote poems on pieces of paper meant to wrap medicines.

Mahaju used to distribute those scrap paper poems to school students who enjoyed listening to him recite poems.

“One among those students was Siddhi Charan Shrestha [another prominent Nepali writer]. People also say he might have learned to write ‘chhanda kabita’, metric poems, with Mahaju,” says Kasa. “In fact the ‘Mahaju’ title was given to him by people out of respect—his real name was Siddhidas Amatya.”

Kasa says that the Kathmandu Metropolitan City is planning to publish a book that will bring together all of his works later this year. Some of his most notable works include Satyasati, Sukhasagar, Bijuli, Sambad, Sanatan Dharma, Samachar, and Siddhibyakaran.

In 2015, to celebrate his contribution to Nepali and Nepal Bhasa literature, a statue of the man was erected in the memorial park in Ratnapark, but many still have no idea about his works. Despite all the activities to commemorate his works, Mahaju still remains unheard of by many Nepalis.

“I think because I’m from Kel Tol, from where Siddhidas Mahaju is, I heard of him many times during cultural protests. But not many younger people know him and it could be because his work largely remains limited to a small group of Newar community, “ says Pabitra Kasa, a member of Nepal Lipi Guthi, who recited a poem to commemorate Mahaju’s work at the event. “Like other Nepali poets, his works are not read in schools and many of his works haven’t been translated yet,” adds Pabitra Kasa.

“His untiring passion for poetry is what makes him so inspiring,” says Mali of Nepal Academy. “Despite all the hardship, he kept pursuing his love for poetry and, through it, inspiring many Nepalis and Newars to preserve and value their culture.”

8.65°C Kathmandu

8.65°C Kathmandu