Entertainment

Art and politics

Five artists collaborate to show that art indeed has a place in politics

Sophia L Pandé

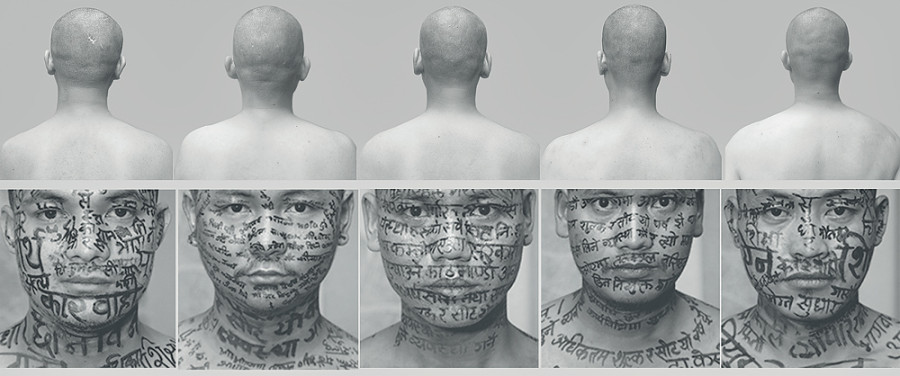

On July 23rd, five young men woke up early morning, shaved their heads, dressed only in black shorts, and wrote on their bodies with permanent marker, before exiting out of the Artree compound in Tripureshwor bare-feet and with their eyes closed. Led carefully by their friends, so they wouldn’t injure themselves, this group had started their walk to Baneshwor in a move to support Dr Govinda KC’s eighth hunger strike against the endemic corruption that shadows the corridors of power in Nepal, allowing those in elected positions to do as they will, reaping the benefits of being able to act with near impunity to line their pockets, and the pockets of those near and dear to them.

Dr KC, a medical doctor, has taken to this particular form of non-violent protest multiple times to demand, among other things, that the government should regulate the opening of medical colleges so that sub-par teaching institutions are not established willy-nilly to extract tens of lakhs of rupees from those who covet the title of medical doctors. Each time the government has acquiesced to Dr KC’s demands, they have reneged on those agreed terms—seven times to date.

Lavkant Chaudhary, Hit Man Gurung, Mekh Limbu, Bikash Shrestha, and Subas Tamang along with Sheelasha Rajbhandari, all of whom belong to the Artree artist’s collective ruminated for four days to plan and execute this protest performance art, which they titled, pretty much on the nose, Culture of Silence. All accomplished artists themselves, the six thought through their objective carefully. They knew that a public performance aimed at civil society cannot be so esoteric as to not be understood by the person on the street who has had no previous exposure to this kind of performance art.

The concept was therefore simple, to walk through the streets for all to see. The closed eyes, for the discerning, were an added, physically rigorous element meant to signify the wilful ignorance in tackling the truly corrupt. The uniformity of the cropped heads and black shorts were used again to represent the commoner, the words written on the bodies of the five men with shorn heads were inscribed by skilled calligraphers using permanent marker to make sure that even without speaking, viewers could understand what the performance was meant to support.

After the men reached their destination, outside the Parliament at Baneshwor, they lined up in front of the barbed wire alongside other protesters who had marched and gathered to support Dr KC (a happy coincidence that increased the number of people who witnessed the performance) and started their simple choreography: standing and facing the crowd so that people could read the inscriptions on their bodies; lying on the ground in abject dejection, pain, suffering, and apathy; catching each other as they fell backwards; and placing their foreheads in a row against a brick wall in order to indicate the pointlessness of our political cycle. Again, all this choreography was designed to be simple yet powerful, using silent action over other mediums to describe the feelings of the Nepali people.

At 2 pm the performers finished up and went home to assess how they felt, and to try and gauge their impact. Writing on one’s body as a sign of protest isn’t a particularly cutting edge, plenty of people, artists and otherwise have done it to augment their message, to underscore their spoken and unspoken words. The question is, in a country like Nepal, where the civil society’s will is essentially disregarded, can this kind of artistic protest make a difference?

It is hard both for the artists and for an observer to truly gauge the impact and outcomes of such an event. While Dr KC’s demands have been both critiqued and lauded, Artree’s political performance art has mainly been a kind of visual phenomenon, amplifying these artist’s concerns via the ubiquity of our social media and the power of the images created during this protest.

So, while the actual protest itself, aside from marking a time in history, may not have had significant impact in terms of moving either the hearts and minds of civil society or our venal politicians, the undertaking itself, amplified by social media, recorded indelibly in images, and exponentially reaching tens of thousands of people via social media, may have created the awareness and understanding that protest can take many forms aside from calling traffic strikes, burning tires, and bashing up people who disagree with you—that even though one may feel stifled, there are ways for our voices to be heard over the clamour of yammering politicians struggling over power.

Yes, the civil society may feel helpless, understandably so, even a man as committed as Dr KC has been repeatedly betrayed by the politicians, leaving a gaping hole where in a normal democracy, if the will of the people actually mattered, would have been a movement of people from all walks of life, protesting the absurdity of our political situation: one where a democratically elected government continues to milk the country and tread on the very citizens who so hopefully came out in droves to vote for them.

Art does indeed have a place in politics; Ai Wei Wei, the famous Chinese artist has single handedly created a culture of cheeky dissent against an extremely bemused authoritarian government. The real question is how we can wield this powerful non-violent medium in a sustained and continued manner so that it can contribute to tangible social change.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu