Entertainment

Pullahari—The monastery and its architectural influences

Visiting the monastery, which is open to all, is a bewildering, enchanting experience. Even the non-religious will find themselves moved by the tranquility and beauty cultivated by the archi

Sophia Pande

For whatever reasons, truly interesting modern architecture has never really “arrived” in this Valley, perhaps because while people have finally now started to understand, and spend money on collecting and promoting contemporary art, architecture has been seen as more of a functional necessity, rather than as a statement-making art form that can change the cityscape, for the better, if done with care.

Perhaps the best, but perhaps also most obvious case in point (I have been accused of using the most glaring possible examples in the past) is the Frank Gehry designed Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, built on the city’s stagnating waterfront and responsible for revitalising a fading town, making it a tourist destination and centre for a wide range of the arts. Imagine our city had it had the advantage of a few glistening buildings like the one in Bilbao, built to blend in but also to highlight the natural beauties of a green valley that is framed by the Himalayas.

Architecture has always been served by religious fervour. Our traditional tiered temple structures were built to house idols, just as the lofty Gothic cathedrals in Northern Europe just kept on getting higher and more airy, striving to reach towards heaven and God himself, every arch and buttress designed to prop up a homage to the divine.

Pullahari monastery, built high on a ridge in the northern hills surrounding the Valley, is at the apex of the three monasteries situated in that area, starting from the Kopan monastery, which is lower down, followed by a closed off, mysterious monastery reputed to conduct esoteric tantric practices (this could be an urban myth, I have only heard anecdotal evidence supporting this theory).

The monastery grounds of Pullahari are enormous, housing two religious buildings, monks’ quarters, gardens, vegetable patches for the monks to grow their food, and living quarters for visiting students.

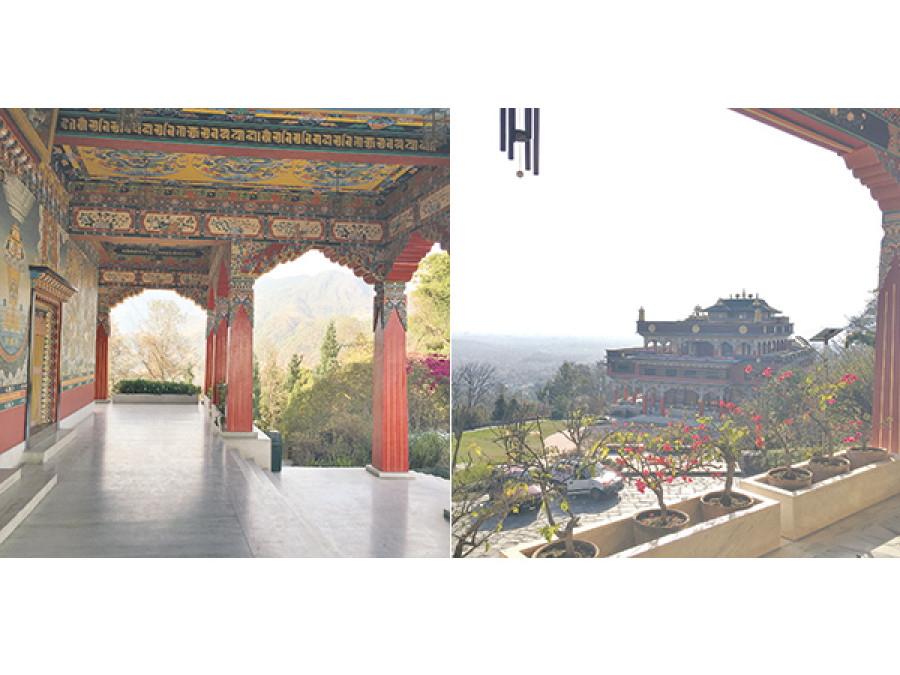

Both of the religious buildings (the lineage shrine hall and the monastery proper) are seemingly fairly traditional when you look at them from afar. It is only when you are circumambulating the shrine hall that one begins to notice the cool white marble floors and elegant long marble benches that magically heat up in the sun (a perfect bed for the many dogs at the monastery).

The deep-rich red pillars that hold up the high-ceilinged pavilions are also similarly reminiscent of classical Western architecture, as are the perfectly landscaped steps leading down to the monastery, which is fronted by an enormous, perfect, concentric circle of laid bricks that leads up to the traditional monastery double doors. The symmetry in the design, the balance of proportions and the manicured gardens all speak more of Versailles than of Kathmandu.

Opened in 1992 and consecrated by the Third Jamgon Kongtrul Ringpoche, the monastery grounds and buildings were designed by an American architect turned monk, now known only as Lama Tenzing. Perhaps this is the answer to the cryptic mixtures of East and West inherent in the design of the monastery, a style that is extrapolated both from Eastern and Western worship traditions, maximising attention to light, and community spaces, both in the gardens and in and around the buildings, so that any worshipper can find a place for themselves, either in the elements or surrounded by the vivid Tibetan religious wall and ceiling paintings that cover almost every inch of the monastery walls.

Visiting the Pullahari Monastery, which, like Kopan, is open to all, is a bewildering, enchanting experience. Even the non-religious will find themselves moved by the tranquility and beauty cultivated by the architecture and landscape. Aside from the odd kitsch offerings here and there, the monastery is unerringly pleasing to the eye, and, if you are so inclined, also to the heart and the mind; this is a perfect example of architecture that both complements and enriches the devotional purposes it was meant for.

Every building, ideally, should be so built then, to reflect and enhance its purpose. Our homegrown architects have plenty they may draw from; architectural traditions can often be extrapolated to include pleasing modern elements should one want to continue on the path of paying homage to our own culture. However, perhaps a few brave souls can walk another path: that of breaking away from fairly conventional practices and creating something truly new—not an easy path, but surely a more interesting one.

8.93°C Kathmandu

8.93°C Kathmandu