Culture & Lifestyle

‘Nest of Spies’?: The stories around Kalimpong as nodal point for Tibet, India and China

Kalimpong serves as a site for unpacking the anxieties around China-India enmeshment.

Prem Poddar

China watchers in North Block or Langley would probably be nonplussed by a book on China and India that focuses, not on the great arid scapes of Galwan or the high reaches above Tawang, but upon a mofussil town stretched along a ridge that points northwards towards the Chumbi Valley which itself swings southwards like a giant axe-head menacing the Indian chicken’s neck.

Last month, Kalimpong mourned the passing of its famous citizen, Gyalo Thondup, elder brother of the Dalai Lama. Thondup memorably transcribed The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong after living there with his Chinese wife Di Kyi Dolkar (née Zhu Dan) since the 1950s.

What was more captivating about his life and times there was the historic location of Kalimpong itself that propelled the narration of his intense involvement as the go-to intermediary for dealing with Beijing, Washington, Tokyo, Delhi, London and other European capitals on the Tibet Question on behalf of the Tibetan Dharamshala government-in-exile. As the Civil War (fought intermittently between 1927 until Communist victory on mainland China in 1949) raged on in China, Thondup had the backing and blessings of the Guomindang generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek who went on to found Taiwan, when the revolutionary regime under Chairman Mao Zedong took over mainland China in 1949.

Kalimpong itself sits not far from the border of Jelep-La, that “tranquil pass” that derives its name from the Tibetan dzi li la, the favoured contact and crossing point at 14,390 feet between Tibet and the eastern Himalayas where the great mule trains of the Tibetan clans Pangdatsang, Reting, and Sadutsang thundered their way to Lhasa. Jelep-La now stands militarised and forbidden for the nosy while the other, more arduous mountain crossing of Nathu-La is a four-hour drive on jeeps from the Sikkim capital Gangtok through the picturesque Tsongmo Lake to a highly battle-ready border, redolent with the smell of diesel and jalebis.

Functioning as the geopolitical coordinates for the Tibetan cause much before the Chinese takeover of Tibet, Kalimpong became the ‘Harbour of Tibet’, developing into the southern terminus of a flourishing Indo-Tibetan trade with both central and outer Tibet, oozing into China. Tibet also stood for China then, as manufactured luxury goods (knocked down cars, Rolexes and Parker fountain pens) as well as piece goods made their way up on mule trains that returned with yak wool and Chinese silver dollars. Fortunes were here for the making, attracting merchants and adventurers who migrated from Rajasthan, North-western India and Kathmandu. Traders also settled and circuited back and forth from Kham (part of ‘ethnographic’ or ‘outer Tibet’) and the Chinese territories.

A leading player in this was Ma Zhucai. It was in the medley of the ‘Tibet-Yi ethnic corridor’ that Ma Zhucai grew up near Gyalthang where minorities (or what are now called minzu or nationalities such as Hui, Han, Khampa, Yi, Nakhi, Hani, Lisu, Lahu, Jinuo, Pumi, Jingpo and others) mingled and diverged while travelling both intensively and extensively.

He worked for a caravan business which traded in Southeast Asia and Kalimpong before he quickly rose to establish his own business, running an extremely successful firm named Zhu Ji. Competing with the Reting, Pangdatsang and Sadutsang fraternities, his firm was among the larger of the 12 or 13 caravan businesses headquartered in Kalimpong where he lived for 41 years. With the proceeds from his trade, he not only helped found the Chung Hwa Chinese School (to which headmasters served as cover for intelligence agents), procured rare manuscripts for a monastery in Tibet, engaged in philanthropy, but also contributed generously towards buying fighter planes for China to scuffle the Japanese.

He was arrested in 1960 and charged with being a ‘Chinese spy-chief’ after the murder of Lama Lobsang Doma in the haat bazaar of Kalimpong. It was to become an international cause célèbre, with the Chinese foreign ministry arranging to extract him via Rangoon in Burma. Thus, even before the 1962 war, the ‘inhumane treatment’ of Chinese nationals became a dominant part of the narrative on India and China. The story of the Chinese residents, Deoliwallahs, sent to the internment camp in Rajasthan is now well known – an early instance of what we now call ‘affective’ injustice.

Ma’s story is later cast in the patriotic mould of a hero returning to his motherland, understandably one of appropriation in a nationalist narrative by the Chinese Communist Party. His grandson founded the Ancient Tea and Horse Road Museum (scripted also as a branch of the Silk Roads) in his old hometown of Gyalthang now rechristened as Shangri-La, a tourist destination standing at about 11,000 feet.

Celebrated as a hero, trading in treacherous places between Kalimpong and Yunnan (erstwhile Kham) he is part of the Historical and Cultural Records produced after Zhou Enlai and particularly after Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. As wenshi ziliao–or memories of the Revolution – his Kalimpong story resonates with subaltern historiography’s endeavour to recover archives that may have been otherwise lost. Seen from our perspective, one must also be clearly cognisant of propagandistic elements that may enter such Chinese projects, for affective injustice runs like a leitmotif through the stories of other Chinese settlers of Kalimpong and its environs.

Against the backdrop of Lord Curzon’s frontier anxiety in the late nineteenth century, Tibet featured as a central burl for the British empire in the Great Game. It was such angst-ridden state subjectivities that fuelled Colonel Francis Younghusband’s invasion of Lhasa in 1904 to ‘open’ up the Forbidden Land. Chary of this, the Qing empire harboured corresponding concerns before 1908–which explains why the embers of this legacy in Republican China smouldered again at the Simla (1914) Tibetan-British-Chinese convention to settle the border. In these negotiations, Charles Bell served as an adviser to assist the Tibetans. A decade earlier, Bell also produced the Final Report of the Survey and Settlement of the Kalimpong Government Estate in the District of Darjeeling, 1901-1903 and his ethnographic records already note the presence of ‘Chinamen’ there.

Chinese settlement in Kalimpong had already begun but took off in earnest only as a result of the bloody Civil War. A reading of Bell’s settlement report serves to identify discursive themes or strategies. The ‘lease’ of Bhutanese land is conquest and resulting (re)discovery, with its double edges of finding and showing. It is a seductive and violent strategy which closely deploys the surveillance and observation of other colonial texts.

Nehru, Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong, willy-nilly the political protagonists in Kalimpong’s tale of intrigue and espionage, would follow colonially prescribed borders of the troubled McMahon Line, with no mechanisms for settlement in place. Other minor characters–Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, British spies, white and red Russians, amongst many others slosh around with traders, aristocrats, mystics, missionaries, travellers, reformers, and subalterns, all presences that provide texture and tone to the palimpsestic world of Kalimpong. The super-diversity of the town becomes a penumbra, a nodal point, that serves as the lens of these exchanges. Reminiscent of the Caribbean islands as the hurricane eyes of the world, this particular space serves as a listening post.

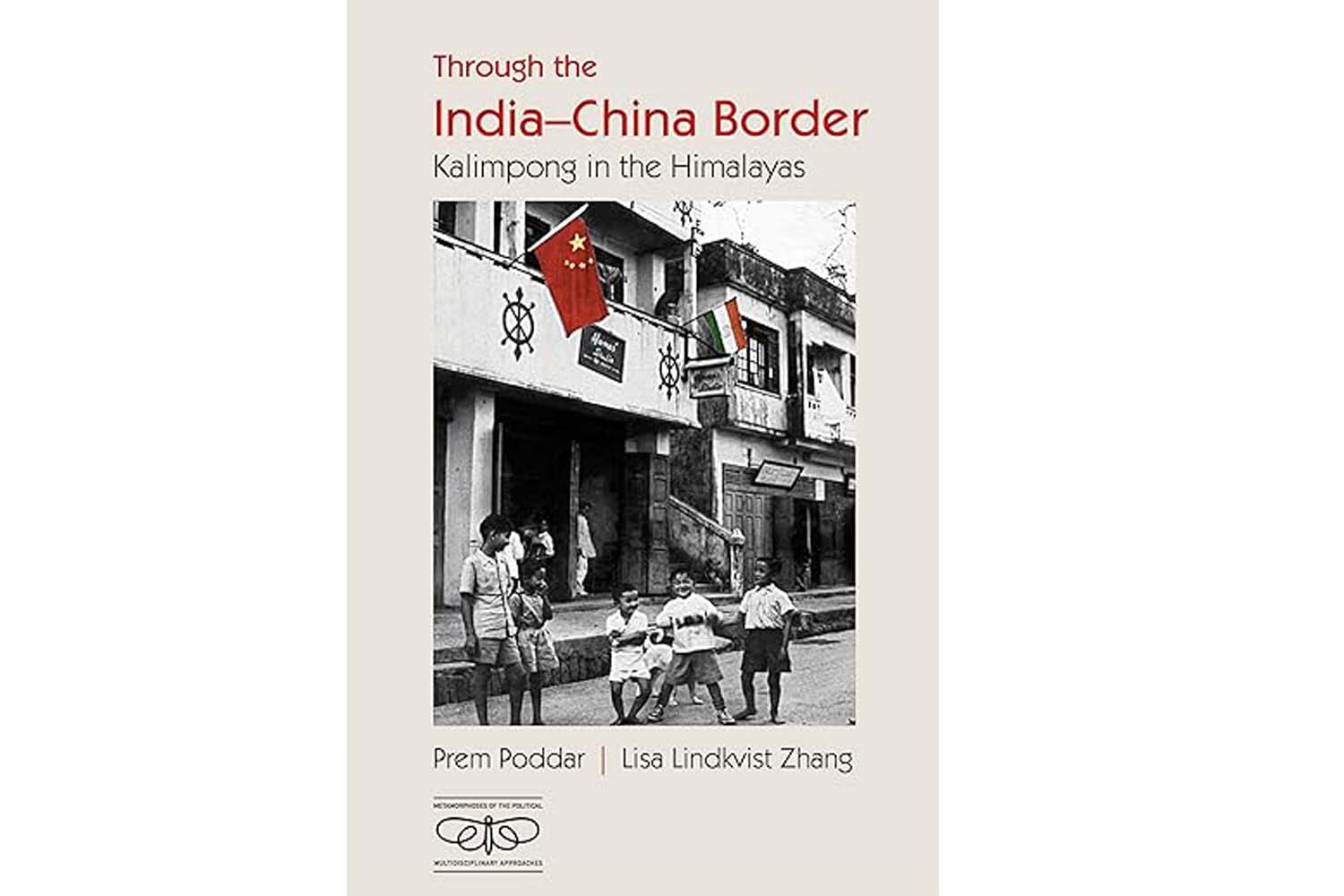

Contextualised in the book Through the India-China Border: Kalimpong in the Himalayas are both Nehru and Zhou’s traded words about Kalimpong being the ‘command centre’ or a ‘nest of spies’ fomenting trouble and insurgency in Tibet and China. Nehru in his finely tuned rhetorical style would also note that ‘sometimes I begin to doubt whether the greater part of the population of Kalimpong does not consist of foreign spies.’ Historians Michael Schoenhals (founder of ‘garbology’ or collection of historical sources from rubbish bins) and Liu Xiaoyuan both record that ‘without exception, every piece of intelligence…came from Kalimpong’.

Beijing’s security orientation was to use teqing (special intelligence agents) not inside Tibet but in Kalimpong. One such Chinese agent who served as the headmaster of Chung Hwa Chinese School in Kalimpong while doubling as Honorary Liaison Officer of the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission was Shen Fumin, who wrote disarmingly that he ‘could not support the British Imperialistic Policy regarding Tibet and China and in fact towards all Asiatic races’. He was later to teach art at the local Swiss Jesuit school whose students remember him fondly as an extremely masterful water-colourist and a stern draughtsman, who with a few deft strokes could evoke a Chinese landscape. And as an old man, he never lost his austere Confucian mien till the end of his days.

Much geopolitical, historical and theoretical ink has been spilled, much atkalbaazi inscribed in generating digital bytes about the China-India enmeshment. It is this anxiety–and not just of the cartographic kind–encoded in the new nation-states (particularly a post-revolution China and a post-colonial India) that craves unremitting unpacking. And Kalimpong serves as a site for precisely that sort of work. Apart from central mainstream dealings, border landers or peripheries cannot feature as fault-lines in foreign policy or mere footnotes in the writing of histories.

___

Through the India-China Border: Kalimpong in the Himalayas

Authors: Prem Poddar and Lisa Lindkvist Zhang

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Year: 2025

Published in special arrangement with TheWire.in

22.16°C Kathmandu

22.16°C Kathmandu