Culture & Lifestyle

Kalalaya puts Itahari on Nepal’s theatre map

Despite lacking a dedicated hall, Kalalaya, a non-profit theatre and arts organisation, proves that theatre is about people, not just performance spaces.

Sanskriti Pokharel

In the past, Itahari was limited to traditional dances for stage performances, lacking theatres and structured shows. Theatre was regarded as an art form exclusive to cities like Kathmandu. This perspective shifted with the founding of Kalalaya in 2008, a non-profit theatre and arts organisation in Itahari.

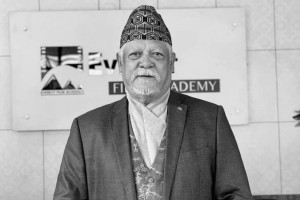

“The only drama we saw was ‘Gaijatra’ in the early 90s. Back then, there were very few theatre shows,” says Sonu Jayanti, the chairman of Kalalaya Theatre.

Kathmandu is where people watch the shows, but places outside the valley, like Itahari, are where much of the behind-the-scenes work takes place. Key elements like actors and technicians come from all over the valley to Kathmandu.

Jayanti discovered this truth during his years in Kathmandu prior to the Second People’s Movement. He observed that artists in the capital faced similar challenges outside its borders. All were pursuing success. This realisation led him to conclude, “If I am going to put in the effort, why not do it in my hometown? With that resolve, I returned to Itahari and established Kalalaya,” he shares.

In the early days, Jayanti’s team focused on organising drama, painting, dance, and other art performances for children. But they realised something was missing—the stories of the artists who came before them.

As they looked deeper, they discovered many people had once been involved in theatre. They wondered how these artists had performed decades ago when no proper theatres existed. So, they started researching and found that as early as the mid-70s, at least 86 people, including Basanta Subedi, Ramesh Bista, Ram Kumar Subba, Kalpana Chaudhary, Bhadra Thapa Magar, and Chandika Niraula, had been active in drama and other art forms.

This discovery sparked an idea—to bring such artists and revive Itahari’s rich cultural history. That idea turned into ‘Tyi Din’, a programme where veteran actors and former dancers performed. With playwright Abhi Subedi as the chief guest, the event received much attention.

During this event, the Kalalaya team realised how artistically rich Itahari had once been. But a new challenge arose—how could they keep theatre alive in the city? Training a new generation of theatre artists seemed like a big task. The answer was ‘School Theatre’—a long-term plan to teach drama to students. The first group had around sixty students. Every year, new students joined, and older ones continued improving their skills. This ongoing cycle became the backbone of Kalalaya Theatre, helping shape young talent and securing the future of theatre in Itahari.

Kalalaya expanded its work beyond the city with the ‘Home Theatre’ initiative. At the time, many believed drama and acting would distract children from their studies. To challenge this idea, Kalalaya introduced theatre not for children but for their mothers. Working women and homemakers were trained in acting and performed plays based on their life stories.

Jayanti says, “Through this, the community realised that theatre wasn’t just for fun. It was a powerful way to tell stories and express oneself.” Slowly, this changed how people viewed theatre, and parents began to see its value in personal growth and education.

Today, the change is evident. “Parents who once hesitated to send their children to the theatre now eagerly enrol them,” says Jayanti. “Sometimes, there are so many students that it becomes difficult to manage them.”

At Kalalaya, theatre is not just about acting—it’s also about building confidence. The School Theatre programme trains students to perform and face an audience. One unique method they use is organising a festival where students from different schools gather. Instead of performing a finished play, they do a live rehearsal in front of the audience. The viewers don’t know it’s a rehearsal, so they react naturally. This helps students overcome stage fear, learn to handle real-time feedback, and become more confident performers.

At Kalalaya, students aren’t given scripts or told what stories to perform. Instead, they choose themes and bring their ideas to life on stage. Anuja Poudel, a former student, says, “We didn’t just act—we wrote the scripts, directed the plays, and led the entire creative process.”

Jayanti guides and supports them, helping them improve their skills. With each performance, he notices their strengths, interests, and potential paths they might follow. In this way, students are introduced to theatre not just as actors but as storytellers and creators. Poudel adds, “When we were kids, the plays we wrote, directed, and acted in weren’t meant to be perfect. They were a way for us to learn the art form.”

Kalalaya’s work is not limited to Itahari. They regularly travel to West Bengal, India, to perform their plays. According to Jayanti, their most recent visit was in December last year in Krishnanagar, India.

The theatre group also organises events in Itahari to showcase their work and learn from others. One such event is Antardeshiya Sajha Rangmanch, where they invite theatre artists from across Nepal and West Bengal. The goal is to introduce Nepali artists to international theatre and encourage cultural exchange. In the future, they plan to expand this event by inviting theatre groups from neighbouring countries like Bhutan and Bangladesh.

Along with other students, Prazal Dulal had the opportunity to act in Nepali plays such as ‘Furfur’, ‘Ishwarlai Chitthi’, ‘Saanndhe’, ‘Dayaam Kantur’, ‘Hirasat’, and ‘Shatru’, as well as in English plays like ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’, ‘Diverging Path’, and ‘Inevitable Appointment’. Directing and adapting the play ‘REFUND’ into Nepali and participating in various national and international theatre festivals has allowed him to experience another dimension of the theatrical art form.

Dulal says, “At Kalalaya, we were taught more than just acting—we were taught to live and feel the character. But before stepping into any role, we did exercises to understand ourselves first. We learned to connect with our emotions and become simple, pure, and flexible like water. This helped us fully grasp the story’s time, place, and mood, and bring the characters to life with depth and honesty.” Jayanti believes that learning acting isn’t just about performing—it’s about discovering yourself.

Reflecting on her theatre days, Poudel shares, “I was a shy kid with few friends. I never imagined myself as an actor. Theatre was an experiment for me, a place where I explored myself. I made new friends and stepped out of my comfort zone. Kalalaya shaped my personality. Without it, I wouldn’t be able to think the way I do now. It taught me how to live life.”

Kalalaya also incorporates poetry into their plays, starting with Manu Manjil’s poems. This initiative inspired students to read and understand poetry, adding depth to their performances.

Sugam Dulal, a product of Kalalaya, reflects, “Kalalaya taught me more than just acting. It showed me how important it is to write and prepare a script to tell a story. This experience helped me become more empathetic and taught me to listen deeply to others’ stories, which inspired my writing. I truly believe I wouldn’t have developed this empathy or these skills without Kalalaya.”

Although Kalalaya has no dedicated hall, they don’t see it as a limitation. Instead, they use the Youth Development Centre’s hall in Itahari for rehearsals.

The group believes in prioritising ‘software’ over ‘hardware’. While having a physical space is important, they believe it’s the people—artists, actors, and creators—that bring drama to life. For them, having the right talent and passion is far more valuable than just a fancy theatre.

At Kalalaya Theatre, most of the audience is made up of students. Keeping this in mind, they create plays that are not only entertaining but also educational, often based on stories from the school curriculum.

Initially, their audience was small, but now they sometimes struggle to fit everyone in. “Thanks to social media, it’s now easier than ever to share our work and reach new audiences. This digital platform has helped spread the word about our productions and attract more people to Kalalaya,” says Jayanti.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu