Culture & Lifestyle

‘Development’ putting communal living in danger

As open spaces in the valley are slowly being encroached, people are deprived of chances to live communally, to rejuvenate mentally and to have a safe space when disaster strikes.

Anish Ghimire

Kathmandu Valley is old and traditional. Many gallis and chowks stand in the heart of the valley that have stood the test of time. These traditional chowks sit in the middle and surrounding it are many closely built houses. “These old houses were built small and were only used for daily household necessities,” says heritage activist and documentarian Alok Siddhi Tuladhar. After finishing their private household chores, people in the olden days used to come out to these open spaces called chowks and do their semi-private activities.

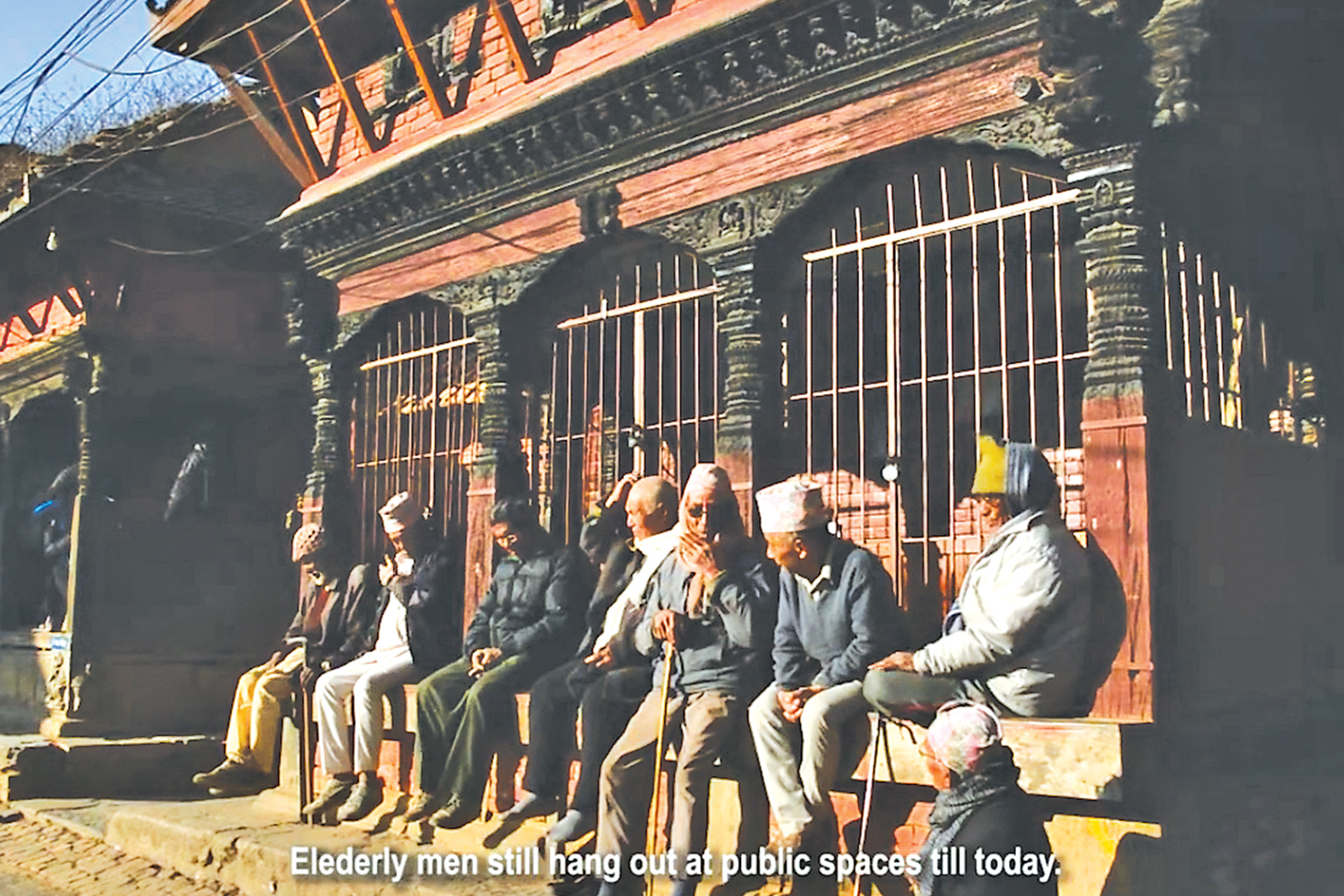

“Whether it is to wash your clothes, comb your hair, or just chit-chat with your neighbours, people came out and spent more time in the open spaces,” says Tuladhar. Having an accessible communal space made it easier for people to come together, connect and ease off from their tiring lives. “When cities were designed like this, it was easier for people to form a bond and to feel healthy,” adds Tuladhar.

Similarly, Professor Bishnu Rai who works as the head of sociology department at Baneshwor Multiple Campus opines that when the valley entered massive urbanisation thirty years ago, feedback and opinions of sociologists weren’t taken. “Humans aren’t just a part of nature. They are in fact, nature. If you try to control humans and not let them be their free-self, then they become disturbed and irritated,” says Rai, adding that a person can be their free-self in open spaces.

In a city as big as Kathmandu, where people lead busy lives, they take their troubles with them to home and work. “By sitting in an open space, talking with friends and family, a person can begin to feel better,” adds Rai.

Surya Tiwari, a 24-year-old resident of the Valley, often strolls in the Sankha Park in Sankhamul, Kathmandu. “There is something peaceful about just walking in an open space. It is so big and you begin to feel insignificant in a good way. Once you realise it is not that deep, then the troubles and worry seem to fade away,” he says. The same type of feeling might be hard to come by when one is stuck in either their room or office.

Basically, lands are used for two purposes. One is for farming and the other is to build infrastructures but there’s also a third kind says Tuladhar. In such land none of the farming or building houses is done, it is just left open.

“Such spaces are called khyah in the Newa language. This word was later adopted by Nepali and became khel, hence the name Tundhikhel,” says Tuladhar. In such an open space, one can engage in individual, communal and social activities while adhering to acceptable public behaviour limits.

While designing a city, if priority is given to open spaces where people can gather and perform their social, cultural and religious activities then it strengthens the human bond. Open space is more than just a space, it is a platform where people come together to express their opinions and to exercise their rights.

Stuti Pokhrel, a 22-year-old resident of Lalitpur, studying public health, looks at the issue from the lens of physical well-being of the citizens. “The first time I realised the importance of open spaces was when the 2015 earthquake hit and we were running from our homes,” she says. In times of disaster, open spaces such as Tundhikhel can be used to provide medical services to the people.

A research article on the same heading published in 2021 by the students of Pulchowk Campus, IOE, discusses how critical the situation is. According to this research, open areas have slowly decreased, been encroached upon, turned into unusable spaces, or heavily developed. This decline in the available open space in the Kathmandu Valley may pose significant challenges for managing crises after disasters.

Talking about the same issue Tuladhar recalls a doctor working in Bir Hospital saying to him, “If Bir Hospital were to be damaged in a disaster, then we will have to put tents in Tundhikhel and provide services from there,” So, these spaces aren’t just about the community coming together but also about being our answer at the time of crisis.

However, open spaces are continually being encroached in the name of development. The rising population demands more and more infrastructure. In such a scenario, open spaces are targeted for the sake of development.

“The land mafia and even local government officials, upon seeing open spaces, immediately think how they can utilise it. Their intention is to commercialise it, seeking to benefit specific parties or individuals, rather than considering the public’s ownership rights to it,” says Tuladhar.

Development doesn’t always have to mean the destruction or eradication of the existing organs of society. Development can also mean the preservation of what matters to the people. Development can also mean proper restoration of the existing system of society.

In a short documentary directed by Tuladhar titled, ‘Kirtipur: An example of revitalization open space management’, Kirtipur has been taken as an example of how open space management can be done by preserving the historic foundation on which the place stands. In the documentary, several Kirtipur residents express their worry about the public spaces built by our forefathers slowly falling into the hands of urbanisation. But even today when one walks into the core of Kirtipur, the city’s community-living style can be seen, as shown in the documentary.

Despite all the encroachment and decreasing of the open spaces, Professor Rai believes that all hope is not lost. Even though the valley is already a victim of an ever-increasing population, the periphery areas of the valley can be planned better, because they are yet to be heavily urbanised.

“Proper planning can be done in new settlements where we can build open spaces for the people,” says Rai. He further adds that frequently visiting such places elevates one’s mood and can bring productivity to the person’s daily life.

28.16°C Kathmandu

28.16°C Kathmandu