Culture & Lifestyle

Spiritual artist Jimmy Thapa’s endless experiment with life

He has been a frustrated runaway, inveterate flaneur, yogi apprentice and a hashish dealer. Now he is content being a ‘spiritual artist’.

Urza Acharya

The time is the 1970s. The place is Kathmandu. Freak Street in Basantapur is the ultimate destination of the hippie trail—a haven where cannabis is sold legally and other drugs (LSD, cocaine) aren’t too hard to find either.

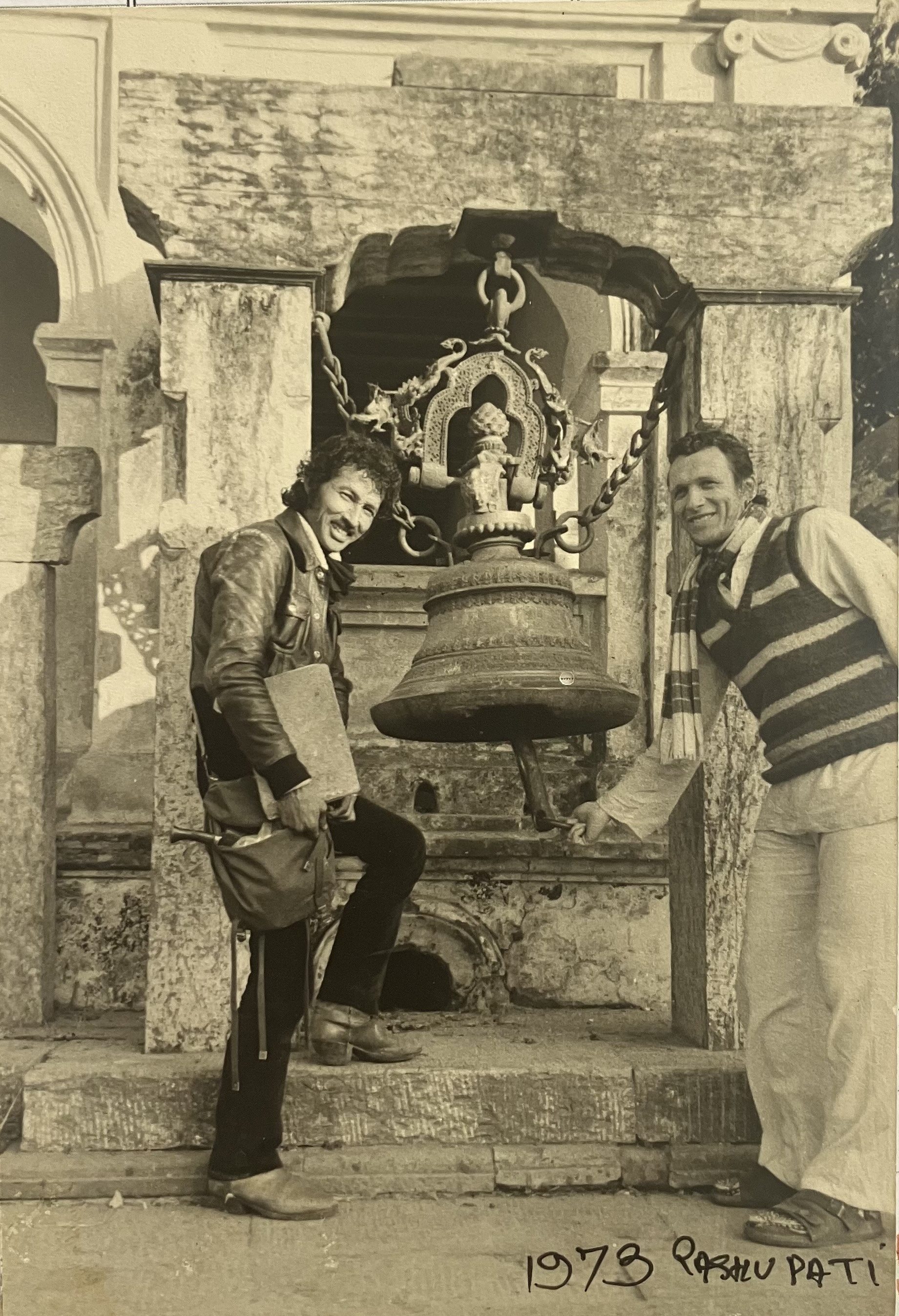

Among many visitors was one Susan Burns, a hippie who’d come to Nepal all the way from the Netherlands. As she was taking a taxi to Swayambhu, she saw a man riding a white horse, dressed in a black outfit with silver details. His sleeves were long and wide—he had donned a hat and a pair of mean looking boots.

That man, as Susan so vividly recalls in her book Magic Days, was Jimmy Thapa. Who’s Jimmy? He’s a 13-year-old runaway who lived in Indian railway stations. He’s a young yogi apprentice who lived at an akhada (resting place for ascetics), learning mantras from other sadhus. He’s Freak Street’s number-one hash seller (back when it was legal, anyway). But most importantly, he’s a spiritual wayfarer and artist whose rather peculiar life has taken him everywhere—from the banks of the Ganga to the lap of Mount Kailash.

I first heard about Jimmy at Siddhartha Art Gallery, my other workplace, where he was set to have an exhibition of his ‘visual diary’—miniature drawings painted in Japanese visiting cards and larger-than-life sketches drawn in Lokta paper. All the drawings are connected to his travels along the banks of Ganga—from Gaumukh to the Bay of Bengal. (The exhibition ran from July 14–19.)

When I see him for the first time, he’s wearing a white colonial-era gentleman’s shirt, complemented by a cravat around the neck. In contrast, his pants are modern, rugged and accompanied by long, pointy boots. For a 75 year old, Jimmy Thapa is remarkably fashionable.

There’s an aura of enigma around him. My colleague claims that Jimmy harbours some mystical power (because he used to hang out with the Aghori babas) and that everytime he sees Jimmy, his head goes blank, like he’s been put in some sort of trance. (That, I think, is mostly fiction.)

It is only after we begin to converse (and let me tell you, he’s something of a professional on that front), do I learn that Jimmy’s life reads like something straight out of a Cohen brothers film—filled with eclectic, absurd tales of life, love and adventure.

Jimmy Thapa was born Suraj Pratap Thapa on October 14, 1947. By his own admission, he never cared for school. His father—a military man—travelled often and so did Jimmy and his family. These constant movements ignited something in Jimmy. Disillusioned by the strictures that his father imposed, Jimmy left home sometime in 1960. He was 13.

“Railway stations became my home,” Jimmy recalls of a time when he would get into random trains without a destination in mind. If he noticed the ticket master coming by, he simply jumped into the next car—quickly figuring out the timings and directions they took to collect tickets.

As he was well-dressed and spoke some English, people always assumed he was lost and were kind enough to give him food. “I never had to beg,” he says. “Back then, people were kind. If you sat near a tea seller, they’d lend you a cup without a word.”

Jimmy took up personas, inspired by the stories he read as a child—some days he was Jeff; other days, he was Henry or Richard. If things got difficult, Jimmy would simply catch the next train and find another place to roam about. “That’s when I became fascinated with temples, mosques, churches and musings about God,” he says.

This way, Jimmy claims he’s travelled all over India, from Bombay to Shillong, Shimla, Madras and even Kochi.

Eventually, these musings brought him to the sadhus at an akhada, somewhere in Uttar Pradesh. They took Jimmy in. He was around 15 at the time. They shaved his head, gave him a loin cloth, and taught him how to swim.

But most importantly, with these siddhas, Jimmy learnt the art of yoga, mantras and meditation. He did that for two years. “But these yogis couldn’t control their desires either,” he says. After seeing sexual trysts in between the men, and even some instances of paedophilia, Jimmy decided this wasn’t the place for him.

“One thing about me, I was free as a bird,” he says. “If I didn’t like a place, I’d just leave.”

The time between his entry to Kathmandu in 1969 and when he left the akhada is still murky. Sometime in between, Jimmy claims he worked as a bellboy at an Oberoi Hotel, where he saw superstars like Shammi Kapoor and Helen.

Finally, sometime in 1969, in his 20s, Jimmy came to Kathmandu. He spent his first night in the Valley under a tree in Tundikhel. Eventually, he found himself at Freak Street in Basantapur, which was bustling with hippies.

Jimmy was transfixed. This was the first time he’d seen people dressed in colourful velvet clothes playing silver flutes and guitars. They were different, happy—musicians, astrologers, poets, writers, painters, and tarot card readers. He finally felt at home among all these misfits.

But things weren’t that easy. There weren’t many Nepali hippies in town. One was Trilochan Shrestha, who was born in 1945 and with whom Jimmy soon became acquainted. Others were foreigners from the US, Europe and elsewhere, making their way to Kathmandu from Goa. But foreigners weren’t too keen on making Nepali friends.

“I had to be friends with these beautiful people somehow,” Jimmy says. “So I opened up a place called ‘Jimmy’s Wagon.’ I put a giant buffalo horn on top of the hoarding board. That’s when people started flocking in.”

Soon he became known as a money-making messiah among the locals, many of whom couldn’t communicate with the foreigners due to the language barrier. They all came to Jimmy to sell their marijuana.

“I always sold the best quality hash—strains that came down from Mustang,” he says.

Jimmy was also the currency man, carrying about euros, dollars, pounds and everything in between in the pockets of his cargo pants. “I made things easier for the hippies. Did everything to help them,” he says.

In old Freak Street, Jimmy was able to experience the full hipster life, trying all sorts of drugs—cannabis, LSD, and even cocaine. But the moments of bliss these drugs brought him were temporary. Jimmy wanted something eternal.

It was also during this time that Jimmy’s artistic career found footing. He used to doodle and draw cartoons as a child, a habit that continued well into adulthood, but he had never worked as an artist professionally. So when American poet Ira Cohen and his then-partner Petra Vogt, who happened to live in Freak Steet at the time, asked Jimmy to illustrate his poetry book, he realised his art was something worth delving into.

When Nepal criminalised marijuana in 1973, succumbing to America’s ‘war on drugs’ policy worldwide, Freak Street started emptying. By then, Jimmy had already been married to his friend’s sister, Astha. Perhaps for the first time, Jimmy felt the need to make money to sustain his family.

He began to work at the casino in the Soaltee Hotel. The wealthiest bunch—kings, princes, businessmen—would come to spend time there, and Jimmy saw it all. He made good money there through which he bought a few acres of land atop the Nagarjun hills, where he still lives with his wife.

It is after the 1980s that life took a calmer turn for Jimmy. He missed the freedom he felt as an aimless teenager roaming around Indian cities without a care in the world. “I was like a dog who’d become untethered,” he recalls. “Sleeping under the stars, learning to read the language of the universe. Nothing beats that feeling.”

So he left home once again. Inspired by Siddhartha Gautam, the prince who left behind the riches and comforts of his palace in search of the ‘ultimate truth’, Jimmy too embarked on his own journey of self-discovery.

“I wanted to study the element water,” he says. So he followed the way of Ganga—painting and sketching whatever he witnessed. From a man selling fruits nearby to crabs basking in the sand, Jimmy’s sense of awareness and observation that these paintings reflect are unique, poignant and touching.

From 1986 to 1996, Jimmy embarked on all sorts of pilgrimages—the Prayag Kumbh Mela, Lake Mansarovar, and Bodh Gaya—documenting everything from faces, landscapes and architecture, both textually and through drawings.

His interactions with sadhus inspired him the most, he says. “When I talk to people in cities, it’s just about gaas, baas and kapaas (food, home and clothing). It gets boring,” he says. “But the sadhus were free from all that. With them, you just listen and learn about life beyond the material.”

Jimmy’s philosophy of life is simple—life is all about acceptance. Even as he looks back on what appears to be an endlessly examined life, he doesn’t like to dwell on the difficulties he went through—homelessness, starvation and perhaps even abuse. Instead, he opts to free himself from all the chains we so gracefully accept in the name of comfort, power, and safety.

Jimmy Thapa, it appears, likes to be himself and live by his own terms. “I have realised that life is too precious to spend on terms set by others,” he says. “I have my own law and my own philosophy.”

13.98°C Kathmandu

13.98°C Kathmandu