Culture & Lifestyle

A year of social movements

Compared to 2020, this year saw a rise in public discourses around pertinent social issues of caste, impunity, and safe spaces.

Ankit Khadgi

The year 2021 has been memorable (both in a good and bad way) for most of us.

During the first three months of the year, a sense of normalcy prevailed as Covid-19 cases had started declining. Businesses and markets started resuming their operations like before. But in April, the country was again hit by another deadly pandemic wave, resulting in loss of lives, jobs, and social security.

But even if times were tough, a few social activists, and common people were actively engaged in social activism, raising pertinent social issues of caste, impunity, and safe spaces in public spheres.

To acknowledge their dedication, working even in unprecedented times like these, the Post lists down a few social movements that took place this year and how they have shaped public discourses around significant social issues.

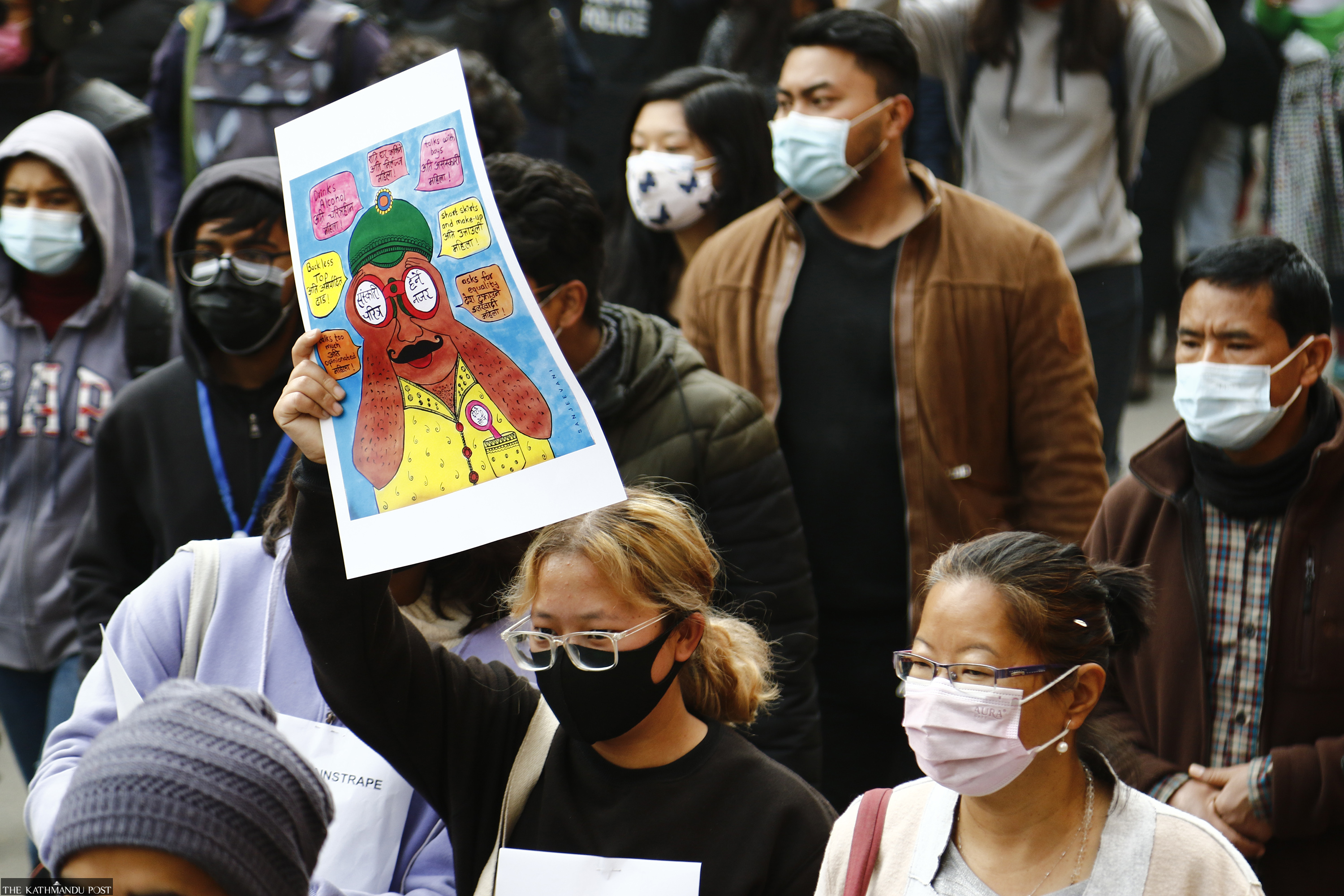

Women’s March of 2021

It’s common to see Nepali women coming together and occupying public spaces, especially in March (the month when International Women’s Day is celebrated). But a month before, in February this year, women from all walks of life came together in the streets of Kathmandu and other cities to demand an end to violence against women.

In Kathmandu, on February 12, a massive rally, ‘Women’s March’, was organised by activists and artists. In the rally, participants chanted slogans of equality, gave speeches against the prevailing sexist social structure, and even recited feminist poems poetry, hoping they could grab the attention of authorities, who have always been indifferent to women's safety.

“Although it was mostly Kathmandu-centric, for the first time I saw so many women from diverse backgrounds coming together for the same cause: equal rights for women and insurance of their safety,” says Sapana Sanjeevani, one of the participants at the protest, who also recited poems during the rally.

Sanjeevani, a poet and artist, believes that the Women’s March was a significant social event. Even if it was just for a day, it reflected the solidarity people have in breaking the patriarchal notions of society.

“Despite all of our differences, we all came together without carrying any political agenda. Unlike other protests and rallies, which are mostly fuelled by political aspirations, we all were there as we wanted to be heard and let people know that women are not going to remain silent any longer,” says Sanjeevani.

Social media activism: How students of St Mary’s ignited discourse around the toxic school environment

On March 23, a current student of St Mary’s, one of Nepal’s prestigious academic institutions, came forward to share her experiences as a student at the school.

In a detailed post on Reddit, the student exposed the school’s toxic environment and how misogyny was normalised within its premises.

“You can't call it an empowering school with all this misogyny and sexualisation of minors. You can't say this school respects and accepts people of all backgrounds and beliefs at all,” the student wrote.

After the anonymous post started getting circulated on social media, many former and present students also came forward and shared their horrific experiences of mental and physical harassment, which they had to endure for years while studying at the social institution.

An investigation was also carried out by the Post, where it found many anecdotal evidences on the school’s tolerance of misbehaviour towards its students.

While holding accountability for the institution’s wrongdoings couldn’t happen in other schools, the St Mary’s incident did contribute to a big change and opened discourses around a safe school environment among both students and parents, says a former student of St Mary’s, who also raised her voice against the school, and spoke with the Post on the condition of anonymity.

“I think the incident ignited discussions around safe schooling environments at a greater level than before. It made many of us– especially our parents– aware of being considerate enough while choosing schools for their children and the need to prioritise the well-being of their kids rather than just looking at the name of the institution,” she said. “We never had such discussions before, but thanks to the incident, people are at least talking about safe spaces, good touch, and bad touch, and other several important things related to the safety of children.”

The rise in the movement against caste-based discrimination

Although many claim that caste-based discrimination no longer exists in Nepali society, the ground reality is darker and different for marginalised people—especially the Dalit community. Caste-based discrimination still plagues our social fabric, due to which Dalit people face atrocities and discrimination daily.

They are harassed, beaten, and even murdered, and they have to get killed for the wider society to acknowledge that caste-based discrimination exists even now.

However, this year, the country saw a huge public outcry and discourses around casteism because of Rupa Sunar.

In June, Sunar, a media professional, filed a case against a so-called upper-caste woman who had refused to rent her house to Sunar because of her caste.

While Sunar wasn’t the first person to use her legal rights to seek justice for the caste-based discrimination she had faced, her decision to seek justice started a discourse on a national level about the perennial casteism Dalit people have been facing since time immemorial, believes Shusma Barali, journalist and activist.

“In Nepali society, there’s this common belief that caste discrimination is a thing of the past. It doesn't happen anymore. If any person tries to bring up this issue, they are shunned down completely and labelled as people who are trying to jeopardise social harmony,” says Barali.

“But caste-based discrimination is a lived reality for Dalits. And thanks to Sunar, the challenges we have been facing for years got highlighted so quickly as many people started talking about it this year because she took a stand,” said Barali to Post through a phone call.

For Barali, who has been actively involved in the Dalit movement in Nepal, the particular incident involving Sunar proved monumental. The incident, she says, prompted conversations among people from all walks of life about the discrimination faced by the Dalit community and highlighted the community’s strength and resilience.

“Rupa’s experiences are similar to mine and many other Dalit people. I salute the courage she displayed as she fought for her rights and questioned the social structures that have never treated us equally,” shared Barali.

Ruby Khan vs State: An arduous battle for justice

.jpg)

Walking from Nepalgunj to Kathmandu for 20 days, Ruby Khan, a human rights activist, and 13 other people hoped they would get justice in the capital.

For years, Khan, 34, along with other people, had been knocking on every door they knew of in their hometown, Banke, to demand a fair investigation into the death of Nakunni Dhobi and the disappearance of Nirmala Kurmi. In August, they had even staged a 19-day protest in front of the District Administration Office, Banke, but the authorities refused to pay heed to their calls for justice.

That’s when Khan and other protestors decided to take the long and arduous journey to Kathmandu and make the authorities hear their voices and demands, as they couldn’t tolerate the injustice the families of Dhobi and Kurmi had to face, says Khan.

“From my childhood, I had decided that I would dedicate my life to fighting against the atrocities women are subjected to. I was always disheartened to see how we are treated in our society and the discrimination and violence we have to face. That’s why it was important for me to actively involve myself in activism and fight against injustices we have been forced to endure,” says Khan, former general secretary of the Banke chapter of the National Womens’ Rights Forum.

Although the government formed an investigation committee, the protestors are not satisfied with the investigation, as they believe the police haven’t taken all of the perpetrators into custody.

“We will keep on fighting as we want justice at any cost,” says Khan. “As women, we have gone through a lot, and we want to put an end to our sufferings”.

Although it’s uncertain if their demands will be met or not, Mohna Ansari, advocate and former member of the National Human Rights Commission, believes that the courage shown by Ruby Khan and other protestors is praiseworthy as it has the power to influence more similar voices, who have been standing against impunity.

“I think it’s important to acknowledge that this is one of the few kinds of protests that has been solely led by women who don’t have enough access to social and economic resources. That’s why I believe this movement will encourage more people to stand against inequalities and discrimination they are forced to face,” says Ansari.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu