Culture & Lifestyle

A changing Kirtipur’s ode to its past

Across the ancient Newa town on the southwestern rim of Kathmandu, murals depicting the town’s culture and traditions have turned into an open gallery.

Srizu Bajracharya

It’s a warm sunny afternoon, and in Kirtipur’s Dev Dhoka, Krishna Kumari Maharjan and her friends are conversing with each other. With Dashain around the corner, the women have decided to halt their work making threads by spinning fibre.

A huge mural depicting women using spindles and spools to make threads and yarns from fibres adorn a nearby wall. The women in the mural closely resemble Krishna Kumari and her friends.

Krishna Kumari, 60, tells onlookers that have gathered in front of the wall that the mural evokes fond memories of Kirtipur, of her childhood, and of her growing up years.

“Until a few decades ago, the majority of women in our town used to make threads and yarns for a living. But things have changed now, and only a few of us continue to do this work,” she says, admiring the art in front of her house. “The painting reflects our age-old tradition so gracefully and also uplifts those of us who are continuing this profession.”

The mural is one of the many that are dotted across the ancient town of Kirtipur on the southwestern rim of Kathmandu. The common thread binding the murals is Kirtipur’s culture and tradition. These paintings provide visitors with an insight into what life was like more than five decades ago.

The mural project is the brainchild of Kirtipur’s local Raj Man Manav.

“I see the art project as an ode to our past. The paintings represent a time, possibly 50 years ago, when Kirtipur was untouched by modernity. Of course, compared to the Valley’s other Newa towns, Kirtipur’s culture, lifestyle, and traditions are still intact, but the town is changing fast,” says Manav. “The project is my attempt to remind people of the heritage we have and share the stories of our town with visitors. It is a project to beautify Kirtipur. And what better way could there be than art.”

To implement the project, Manav first approached experienced artists in Kirtipur, but “they declined to take part.” That’s when he roped in young Fine Arts students from Lalit Kala Campus.

Work began in October last year, and since then, four Fine Arts students have already completed 20 murals and will be completing 20 more in the upcoming months.

One of the four student artists involved in the project is Kirtipur local Rojan Maharjan.

“As artists, being asked to take part in such a huge public art project is a great feeling, and it also comes with great responsibility. As a local of Kirtipur, I am aware of how much our culture and tradition mean to us, and we know that the stories in the artworks hold a lot of meaning to the people of our town,” says 22-year-old Rojan.

For the four young artists, the project has also provided them with a huge learning opportunity.

“With each mural, we feel like we have grown as artists. The project has not only allowed us to hone our skills but also made us see the role art can play in communities,” says Sirapa Shrestha, Maharjan’s classmate. “Since the project is backed by Raj dai, it has proven very easy for us to work. Dai is very efficient at getting the required permissions from the community members as well as government officials and dealing with all sorts of barriers that typically crop up when working in communities.”

As the owner of Newa Lahana, one of Kirtipur’s most popular Newa restaurants, Manav is a well-known figure in the local community.

The public art project, for which Manav has also coordinated with the Kirtipur Municipality, is part of his bigger dream of making Kirtipur a popular destination for both domestic and international tourists.

“Once all the 40 paintings are done, each painting will have a description that further elaborates the subject of the painting and its significance,” says Manav. “Kirtipur will become a sort of open gallery, and this will bring more footfall to the town, and it will help local businesses.”

Murals are not new to the Valley’s art scene. In the last decade, many artists have coloured the Valley’s public walls independently and as part of various initiatives like Kolor Kathmandu, Prasad, Kathmandu Triennale, and Dalit Lives Matter Nepal.

But what is distinct about the murals spread across Kirtipur is the absence of modern styles found in contemporary murals. The paintings, unlike modern murals, are not vibrant with striking colours; they are simple, traditional, and easy to understand and consciously avoid figurative elements. They bear the vibe of the quaint Kirtipur with its use of realism.

The paintings subtly declare to passersby and onlookers how art and culture play an essential role in bringing people together and highlighting a town’s history and tradition.

In one of the alleyways of Kirtipur’s Tha: baha, a large mural of a funeral procession adorns a wall. For the residents of Kirtipur, De: khoo ghat is the main cremation site, and for centuries, funeral processions in the town have passed via Tha: baha. The funeral procession mural pays homage to this aspect of the town’s tradition.

Moti Bahadur Maharjan, a local, says the murals across his town have given him more reasons to be proud of the nuances of his culture.

“Getting to share what Kirtipur is to visitors through murals gives us [locals] a sense of pride,” says Moti. “Not just visitors, even younger generations of the town’s residents can learn a lot about their tradition and culture from these paintings. I have a lot of respect for the artists who have done these paintings.”

A few minutes walk from Dev Dhokha is Dyo-dhwa-kha. The area is home to a mural of the Lakhey Paa. In the mural, a man sits in a cone-shaped hay structure and in front of him are several bowls of food. According to a local folklore, a demon used to terrorise the town’s residents. To appease the demon, the townsfolk would offer a man as human sacrifice along with food and a barrel of liquor every year. This ritual, according to the folklore, was done at Dyo-dhwa-kha.

“Legend has it that when Bhimsen [the god of trade and business] visited Kirtipur, he killed the lakhey and freed the townspeople from its terror. But to this day, every year during the Dhelu Jatra, which falls in November/December, the residents of the town pay homage to the folk tale and offer food to the demon,” says Manav.

For the four artists involved in the project, it didn’t take long to realise what the project means for many locals.

“While we were making the mural of women spinning threads at Dev Dhoka, a few local women came to us with an antique charkha (spindle) to show us how it should look in our art,” says Sirapa, a resident of Dhalko, Kathmandu. “These days, when we are painting, people often come to suggest elements that should be part of the painting.”

For Sirapa, working amongst Kirtipur’s close-knit community has also made her realise what years of urbanisation has done to Kathmandu’s Newa communities.

“The rapid pace of Kathmandu’s urbanisation has inflicted a lot of damage to the social fabric of the city’s Newa communities. But in Kirtipur, I still see a great sense of unity and respect for the local culture and tradition, and most residents know each other,” she says.

But for many of the town’s elders, the changes their beloved town has undergone are all too evident.

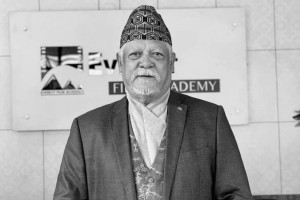

Bajramuni Bajracharya, 49, a local of Kirtipur, has seen the changes that have swept Kirtipur in the last three decades.

“A lot of new buildings have come up, and many locals have left their traditional professions as well,” says Bajracharya, who is also a cultural expert and a lecturer at the Department of Nepal Bhasa at Patan Campus. “The fact that these paintings evoke nostalgia among the town’s elderly residents is a testament to how much Kirtipur has changed.”

To the town’s residents, the murals are a reminder of what they had, says Bajracharya. He believes that community members and government stakeholders must ensure that these culturally and traditionally significant paintings are protected and well-maintained.

“The murals have managed to generate a buzz and made people realise the importance of art, culture and tradition, and now the thing the town needs to focus on is how to take that realisation forward and create a lasting impact. For that to happen, the community and the government stakeholders need to get more involved,” says Bajracharya. “Good initiatives need to outlast time.”

As the artists completed more murals, Manav, who conceived the project, is proud of the interest the murals have already managed to attract.

“This whole initiative is about knowing our past. And that is something we keep forgetting as we chase after our lives in this modern world,” says Manav. “I believe that it is only when we understand our culture and tradition do we get a chance at saving them for the future. And in Kirtipur, I am just getting started.”

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu