Culture & Lifestyle

‘I wanted to take my own path’

Mitthu Tharu has quietly emerged as one of the most notable upcoming artists in recent times—highlighting much of Tharu art and culture.

Srizu Bajracharya

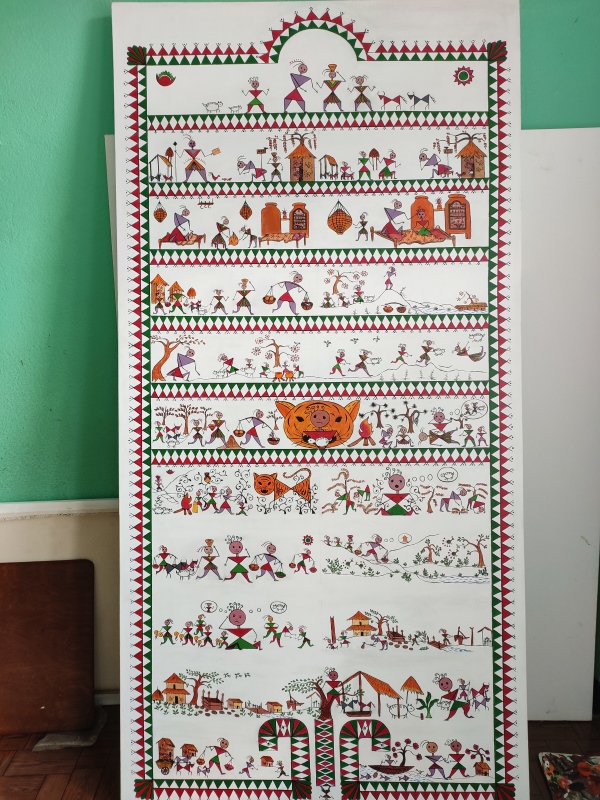

Mitthu Tharu’s art for Chhabilal Kopila’s children’s book ‘Kailari’, a story representing the migration of Tharu communities from Dang to Kailali, has just about made everyone curious in recent times.

Tharu’s eccentric geometric-shaped characters illustrate an essential event that shaped the lives of many Tharu people who had to leave behind their lands in the 1950s-60s when they were forced to work as agricultural labourers by the zamindars who occupied their lands.

To tell this tale, Mitthu Tharu had taken the traditional Tharu art form of astimiki and translated Kopila’s story effectively delivering a nuanced picture of the community’s hardship.

His work was also celebrated as this was also the first time an artist had used the Danguara Tharu style to tell a fictional story. And last year, he was awarded Lalit Kala Bishesh Puraskar from Nepal Academy of Fine Arts.

“I didn’t think I would get such a positive response, and I feel blessed for how people are appreciating my work,” says Tharu modestly from Kailali who is currently visiting his home.

Tharu has, for now, slid away from the outer world and into his zone—where he is still figuring himself out as an artist. Tharu now is in his last year as an undergraduate student at the Lalit Kala Campus of Fine Arts.

He recently also registered for an art studio, Nawayuga Art Studio, in Kailali to promote Tharu art and encourage commercial production of their art and craft.

But for Tharu, his art series for the book ‘Kailari’ were deeply personal as his own family’s story resonates with the story the book represents. Tharu’s jijubaje, great grandfather, and his father both were Kamaiyas, bonded labourers. And growing up in Bhagalpur, Kailali, Tharu never really pictured he would have a different life; one with education and finding one’s own path in life.

But at 13, when he came to Kathmandu as a domestic help, he saw his life slowly changing. The first few years were strange and unfamiliar as he navigated his life without his family—the prejudice of the society against his presence was quite apparent. So, in his school and college days, Tharu hardly communicated for his artistic pursuits. And for people around him, his art was intriguing but they never really thought Tharu would think of art as his calling in life.

“And I never really dreamed big; my life was defined when I stayed in Bhaktapur with a family. I went to school and came back, helped out in chores, drew with tika powders and moulded shapes with the kalo mato from the farmland of the owners, and just doing that I was actually happy,” says Tharu, remembering his younger days with nostalgia. “But in the later years, I realised that I wanted to paint my path forward,” he says.

And the more he found himself getting devoted to art, the more he received the response that ‘art cannot sustain one’s life’ and practically such a pursuit is foolishness.

“But I wasn’t deterred; I wanted to show them that things could actually work. And so, I also enrolled myself in Bijeshwori Fine Arts College. It was a struggle to convince people around me that this was what I wanted to do,” said Tharu. “Previously, I studied commerce, but I really was not interested in the subject, and I couldn’t get through the exams. And so, after that, I had been working. But you know how it is when you have your mind bent on something; I felt this uneasiness every day—so I had to do something,” said Tharu.

After that Tharu also joined Lalit Kala Academy, and in between, he also went to teach art in two schools. Tharu was making a regular income, he says but he found himself restless as he couldn’t find the time to dedicate to his creativity.

“So, I left teaching art and started approaching art shops in Thamel, and galleries to buy my works. I didn’t make enough, but I was able to earn, and I was thrilled that I was able to prove that artists could make their lives. And I also started participating in art programmes,” says Tharu humbly.

It was in one such programme that Tharu met Ashok Tharu, a Tharu cultural expert, and Narendra Chaudhary, the manager at the Tharu Sanskritik Sangralaya in Chakhaura, Dang, who inspired him to think of his roots as an artist. And later, the two approached him to contribute to the Tharu museum. When Tharu heard the proposition, he was overjoyed, he says.

“It felt like a dream; I was literally floating,” he says.

“One moment, I was in my class and in the next, I couldn’t hold myself together with the happiness of being part of that project. I danced and sang my way to Naya Buspark and even forgot to inform my guardians here. I was so happy that I kept telling everyone I was going to make Dangi Sharan’s statue. I don’t even know if anyone knew what I was talking about,” says Tharu, his voice resounding the excitement of that day.

It is believed that Dangi Sharan was the first Tharu king in the medieval period and according to Tharu no one had ever attempted to make his sculpture. And that was also why Tharu was excited about the venture. This was one of the most significant milestones in his journey of becoming an artist, says Tharu.

After that in 2019, alongside Lavkant Chaudhary and Kiran Shrestha, Tharu created an ashtimiki installation at the Siddhartha Art Gallery in the exhibition ‘Masinya Dastoor.’ The exhibition echoed the Tharu community’s adversities and brought forward how the indigenous group were excluded from many parts of development years. Their work reflected the tradition of Tharu mural painting during the festival of Krishna Janmashtami. And that exhibition was one of the highlights of 2019’s year in art.

In a way, Tharu believes he was lucky to have met people who wanted him to continue his path of exploring himself as an artist and an artist who could explore his roots. He remembers that he was hardly aware of the art present in his community when he was a teenager.

“It was more a ritualistic thing, and with the conditions we were living in we never really took the time to appreciate our culture. And I didn’t even know the artistic scope; I didn’t know galleries or artists’ studios existed before coming to Kathmandu. Life was small,” he says.

Today, Tharu is among the few artists who have been telling more about the Tharu people’s way of life than any other. He is also known as a sculptor and visual artist. And as he grows as an artist, it has been equally important for him to tell stories of his community through his work.

According to him, traditions like astimiki paintings that depict nature and evolution of life have slowly become defunct in practice. And even today, people are not able to distinguish Tharu art. “They usually think of Mithila art when thinking of Tharu art, which tells that art from our community still is unknown and undervalued. But if we are to conserve the cultural practices we need more artistic efforts to take place,” he says.

“Moreover, artists need to modify and work on these traditional art forms. They need to use this traditional form to tell stories of their own imaginings,” says Tharu. “That is the only way we can assure that this tradition will be transferred to the future generation,” he says.

However, Tharu believes he has not yet found his defining style to call himself an artist of a certain identity. Although his works reflecting the Tharu culture and lifestyle have brought him on the spotlight in recent years, Tharu is still exploring himself, he says.

Looking back at his journey now, Tharu is happy with the choices he has made. He is proud of his grit to do whatever it takes to make it into art. He has participated in over a dozen exhibitions and lately, he has been driven to introduce Tharu art locally and internationally.

Today, there’s a lot he wants to do to change people’s way of looking at Tharu art, and for him, things are just beginning.

The 32-year-old now is more confident about his future in art. “I think being adamant to my decision of becoming an artist was one of the best decisions I made for myself,” he said. “And I will forever be grateful to the family I met after coming to Kathmandu because through their support I found my pace to a different outlook in life,” says Tharu.

And there’s a greater responsibility he now feels as he settles in with his dream, that of addressing youths like him in his hometown who still are unaware of their possibilities in life. Although his journey has been challenging but promising, he hopes it will be easier for the other youth from his village as times change.

From dreaming of making a career in art only a few years back, today, Tharu has become calmer about his calling. He doesn’t feel pressured, and he no longer is inclined to prove to anyone what an artist can do and that he is an artist.

“Now I have realised becoming an artist is not merely about making a career out of it, or making achievements but committing to the pursuit and process,” he says.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)