Culture & Lifestyle

How Mukti Singh Thapa makes paubha and thangka his own

The traditional artist’s work is peculiar and culture defying, and that is his legacy..JPG&w=900&height=601)

Srizu Bajracharya

When Mukti Singh Thapa was in his early teens, he was a free spirit. Roaming around Bandipur, his hometown, he painted whatever interested him, he says. What would this reality look like on paper, he would think, and just sit and draw for hours.

At school, during breaks, he would spend his time in the library trying to imitate images he saw on books and sometimes he would sneak out comic books to practise the strokes of the images in them. “I enjoyed drawing things more than anything. I was a curious kid, I wanted to try making everything,” says Thapa, laughing heartily at his Jawalakhel-based work studio.

And Thapa was famous for his art in school, he says. Besides his drawings, he would also articulate designs for clothes as per people’s request. And people would willingly pay for it, he says. He would save every penny for his colourful imagination. Today, almost six decades have come to pass, and Thapa in many ways is still the curious boy he once was, unconventional and purposeful with his thoughts.

He is known mostly for his meticulous paubha and thangka works, but he is also appreciated as a modern thangka and paubha fusion artist, with his works bearing the nuances of thangka, paubha, and Mithila art. But ask him what he identifies with most and he says he dislikes and disapproves of such identities.

“I just don’t wish to be boxed. As artists you should try to strive beyond a category because then you will be able to do more,” he says.

“My expertise is in different forms of traditional art. I am an artist who uses traditional art to express my thoughts, and if I try, because I have learned thoroughly the traditional skill, I can work to make paubha, thangka, Mithila, Madhikarmi, Mughal works. But that doesn’t mean I should be classified as being just a paubha or a thangka artist,” says Thapa, adding he also delves in imaginings beyond the world of the deities.

Thapa for years has been using different traditional art forms as mediums of self-expression. He has created a variety of works on pivotal issues of patriarchy, sexuality and faith. And thus, as an artist, he has stood out for his progressive ideologies.

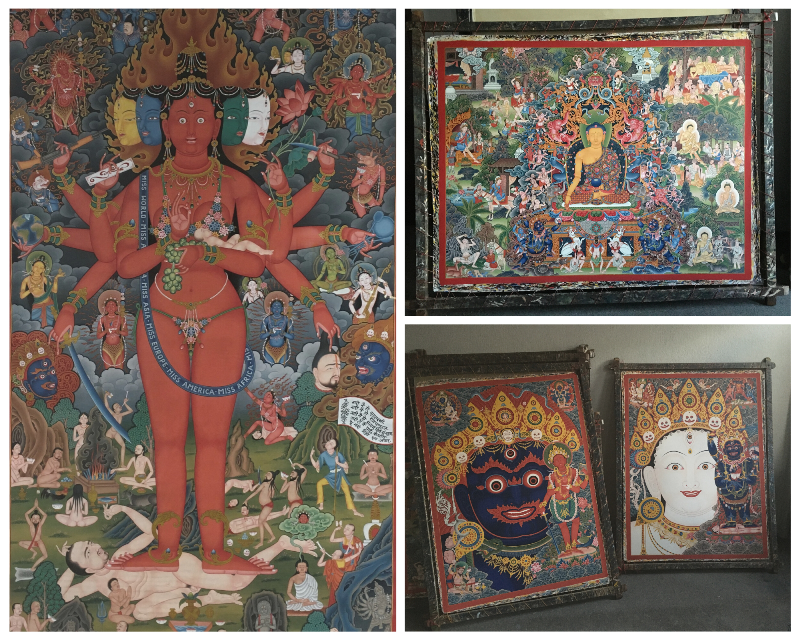

At his studio, a huge painting of Buddha’s life shows exactly how Thapa thinks: his interpretation of Buddha’s life can be unsettling for some. Unlike the many artworks that put Buddha’s life on a pedestal, Thapa’s work makes Buddha look more human: we see a poor-looking Buddha after he leaves the riches of his palace and is teaching his disciples.

“I have always loved making works that depict my own imaginations and views more than thangka and paubha. My thoughts and rationale drive my art,” he says.

One of his most memorable works is at the Museum of Nepali Arts, titled ‘Naari’. The work is unusual and provocative. In the painting, he presents a woman as a deity with eight hands and five heads, representing the five celestial Buddhas in a woman’s body. There’s an intermix of ideas on faith that represents both Hinduism and Buddhism.

But he also adorns the woman with a sash that reads, ‘Miss World, Miss Asia, Miss Europe, Miss America, Miss Africa,’ and behind the central image he assorts many small representations of women deities, men meditating and worshipping in the work.

It is clear that Singh with his work hopes to address gender inequality and social issues. And he chooses to work with a mix of thangka and paubha’s stylistics to be able to constructively build a world inside his image.

“It gives me more space to tell my thoughts, as I can work in minute to extensive details using this art technique,” he says.

Thapa today is one of the most respectable artists in the country. And is also one of the master artists behind the ongoing restoration of the 16th century murals in the monasteries of Lo Manthang. His expertise on paubha has been valuable in training a workforce for the restoration of murals in the monasteries.

However, his journey to becoming one of the most distinct faces in the Nepali art world has not been easy. Thapa is a self-learned paubha artist but he had struggled to find an art teacher for himself when he wanted to learn and polish his skills.

“There were no teachers at the time interested in teaching me, plus because I was from a different caste and these art styles were sacred, people were not willing to share the knowledge,” he says.

Thapa remembers the first time he saw a thangka work was when he was a lanky 18-year-old. For him, that moment was spell-binding—and awakening. He just knew that he had to learn the skill of making such art.

And when he arrived in Kathmandu, he started working part-time at Majdur Enterprise, where he used to count papers and iron them. Then, later he started working with Clive Jeeward, a British expat at Kathmandu Guest House, where he started crafting wardrobes, and chokse, Tibetan tables. There he also met Tibetan thangka artists, who further drove his interest in the traditional art form. He would hang out with them and try to find a teacher for himself. He finally did manage to, at White Gumba behind Boudha, two Tibetan gurus, Karsang and Tengda, who had come from Dharamshala.

“I learnt a lot from them, on how to make the characters, and the cuttings. And slowly I started making my works and selling them at Jhochhen,” he said.

“I was also interested in paubha but no one wanted to teach me at the time. So, I started roaming around temples and monasteries, trying to emulate distinct characters, cuttings and iconography of paubha works,” he says. Thapa put his everything to learn the nuances and norms of paubha, investing time in his own research.

And then in 1977, Thapa participated in an art competition organised by Nepal Academy of Fine Arts, where his paubha won the first prize among artists like Prem Man Chitrakar and Batsa Gopal Vaidya. It was a surprising success, as no one knew who Thapa was. It was as though he came out of nowhere and took over the art scene of the late ’70s.

Thapa dexterously produced thangka and paubha works but simultaneously worked on his own art style that was influenced by techniques of paubha and thangka.

“Paubha basically is a design technique that can be done in five mediums: stone, metal, wood, ceramic, and cloth, while thangka is more comprehensible to people’s understanding; it is more straightforward,” he says. “But my work is neither thangka or paubha, it's a fusion of sorts.”

According to Thapa, thangka is more illustrative and shows landscape works, whereas paubha is more a design painting that depends on lines and cuttings. While his work borrows techniques from the two styles, over the years, Thapa has developed his own command over the technique.

But over time, the works of thangka and paubha have degraded, he says. And Thapa fears that the future will be devoid of artists who can continue traditional art or contribute to the heritage of art.

“The general people don’t really know what is thangka and paubha and so, they blindly believe every work presented to them as paubha and thangka. But I think artists need to work on their precision more and really try to learn the authentic art. Right now when I see the works of the new artists, I see that they are confused,” he said.

However, people are not that keen on learning traditional art today, says Thapa. “That interest in learning traditional art is declining and perhaps because our culture is not that open to learning. Everyone thinks they have already learned and they feel small when they have to be a student again,” he said.

Thapa’s cynicism about the future of traditional art comes with his own experience. Four years ago when he won the Arniko Puraskar from NAFA, he had ventured to teach thangka and paubha to young artists from Bhaktapur, Patan and Kathmandu. In total, he had taught over 61 students, and he hoped for the students to continue learning with him. But none of them continued.

“This just shows how things are changing. But I had hoped at least a few would stick around to learn but that didn’t happen,” he says.

However, in contrast to the traditional norms Thapa adheres to, he is also one among the few traditional artists to be experimenting with traditional techniques. And he believes this is important as times are changing and with it people’s interest. “We are drawing closer to the time where images of deities will no longer be important to people,” he says. “And this will directly affect its market.”

To provide evidence to his judgement, he recalls how his paintings after being confirmed for acquisition were rejected by a private museum owner in Seattle, the US, over 20 years ago, when he told the buyer the works depicted religious deities. And Thapa expects the situation to get worse in the years to come with the ongoing economic crisis in the world.

“The market for religious painting is shrinking, and so, we need to be able to make works that can engage people’s attention, works that are meaningful to the current time,” he says. “We need to be ready to experiment and explore more ideas with our traditional art.”

But now at 64, Thapa is slowing down. He is not as energetic in completing a number of works in a year. Rather, he now lives contently and has surrendered to his mood. “Aajkal jhijho lagcha,” he says, which can be translated to “These days, I get lazy”.

So, on days when he finds himself in his spirit, he spends hours and hours in his studio. And when he is not happy with the depiction of his imaginings, he tears his work right away even if he has spent hundreds of hours to the work.

“You see there’s plenty of topics to delve into, but if your work is not able to exude an essence, if it is not able to tell your expression, what good is that work?” said Thapa. “As artist’s we have to challenge ourselves to work on that, patiently and bravely; as an artist you have to try everything to meet your vision, your visual perception.”

“Because for an artist, the rendition is everything.”

13.85°C Kathmandu

13.85°C Kathmandu