World

1.5 million children have lost parents to pandemic; potential brain gateway for virus found

A roundup of some of the latest scientific studies on the novel coronavirus and efforts to find treatments and vaccines for Covid-19.

Reuters

The following is a roundup of some of the latest scientific studies on the novel coronavirus and efforts to find treatments and vaccines for Covid-19.

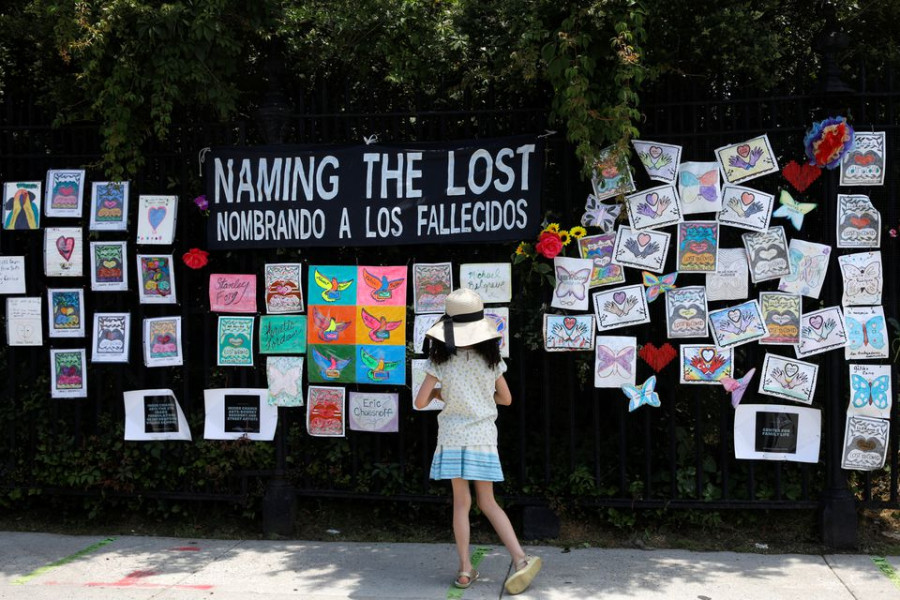

1.5 million children lost parents to Covid-19 so far

During the first 14 months of the pandemic, an estimated 1.5 million children worldwide experienced the death of a parent, custodial grandparent, or other relative who cared for them, as a result of Covid-19, according to a study published in The Lancet on Tuesday.

The orphanhood estimates are drawn from mortality data from 21 countries that account for 77% of global Covid-19 deaths and from the United Nations Population Division. "For every two Covid-19 deaths worldwide, one child is left behind to face the death of a parent or caregiver," Dr. Susan Hillis from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Covid-19 Response Team, who led the study, said in a statement.

The number of Covid-19 orphans will increase as the pandemic progresses, she added. There is an urgent need to prioritize these children and "support them for many years into the future," Hillis said. Study coauthor Lucie Cluver of Oxford University said: "And we need to respond fast because every 12 seconds a child loses their caregiver to Covid-19."

Potential brain gateway found for coronavirus

Researchers have found a potential route of entry for the coronavirus into the human brain that may help explain the effects of Covid-19 on the brain and nervous system that have plagued many patients. To date there is no evidence that the virus directly infects neurons - the brain cells that receive and send messages to and from the body.

In a new study, experimenting with an artificially grown mass of cells created to resemble the brain, researchers found that neurons seemed "impervious" to the coronavirus, said Joseph Gleeson of the University of California, San Diego. But cells called pericytes, which wrap around blood vessels and carry the surface protein the virus uses for entry, proved to be a different story.

When researchers added pericytes to their artificial brain and then added the virus, "we found incredibly robust infection," not just of the pericytes but also of the neurons, Gleeson said. They report in Nature Medicine that the pericytes served as "factories" for the virus, from which it could multiply. The primary targets were astrocytes, which have crucial roles in regulating the brain's electrical impulses, providing neurons with nutrients, and maintaining the "blood-brain barrier" that shields the brain from foreign substances.

The findings, Gleeson said, suggest "pericytes could serve as an entry point for SARS-CoV-2," which could either lead to local increases in the virus or to inflammation of blood vessels that can cause stroke.

Vaccine boosters not yet needed, researchers say

Two doses of an mRNA vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech, or Moderna are effective at neutralizing the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus that is or will soon be dominant in most places, suggesting immediate booster doses are not likely needed, researchers said.

They did not measure the vaccines' ability to protect against infection in the real world. In their lab experiments using blood samples from vaccinated volunteers, however, Delta's mutations caused only low reductions in the proportion of antibodies that could neutralize the virus, they said.

Mutations in the less prevalent Beta and Gamma variants reduced antibody neutralization capacity more significantly, but not to a point where vaccine recipients would appear to be unprotected, the researchers reported on Sunday in a paper posted on medRxiv ahead of peer review.

Vaccine boosters may be needed in the future to help overcome some variants, coauthor Akiko Iwasaki of Yale University said in a tweet on Tuesday. Her team also found that overall, neutralizing antibody levels after vaccination were higher in Covid-19 survivors than in uninfected vaccine recipients.

"This is not surprising," Iwasaki told Reuters, "because infection itself induces immune responses, which were boosted by the two doses of vaccines."

24.49°C Kathmandu

24.49°C Kathmandu