Valley

Valley’s poor worry about food as authorities prepare to extend lockdown

Rights activist Mohna Ansari says the state must support the needy in times of crisis.

Anup Ojha

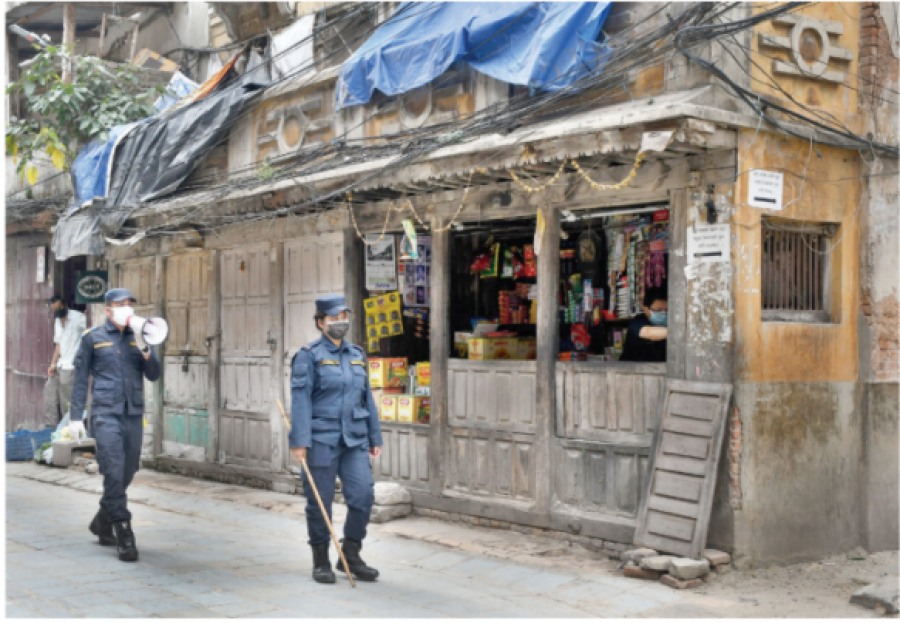

The Kathmandu district administration has indicated that the Covid-19 prohibitory orders that are in place in the Kathmandu Valley for the past three weeks will be extended for another week.

Kali Prasad Parajuli, the chief district officer of Kathmandu told the Post on the phone on Monday that along with the extension, the morning shopping hours also could be reduced to reduce crowding.

The chief district officers of Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur had imposed the prohibitory orders in the Valley on April 29 amid record spikes in Covid-19 infections and deaths across the country.

The prohibitory orders, which are in place in almost all districts of the country, have restricted all non-essential activities and put most people out of work. People working in the unorganized sector who have little savings are the hardest hit. Over 70 percent of the country’s population earn their livelihoods in the informal sector.

“We have run out of food and money because I have been jobless for over a month now,” said Ganesh Nepali, 40, who lives in a squatter settlement at Sinamangal, Kathmandu with his son and wife. He also shared that his wife is suffering from nerve compression and he has no money to treat her.

“When they announced the lockdown last month, I bought 10kg of rice, 2 kg of pulse, 3kg beaten rice and two liters of edible oil. But that all is gone now and I have no money,” said Nepali, who worked as a bricklayer. It’s been a decade since he and his wife left their village in Makaibari of Dolakha district in search of a better life in Kathmandu as the land they owned didn't produce sufficient food for his family.

Like Nepali, Krishnaa Basyal, 33, who lives in a rented room in Kirtipur with her husband and a seven-year-old son has a similar problem.

“Last year, the lockdown lasted for four months but we had some savings so somehow we managed to pull through. But now it’s getting tougher,” said Basyal.

Her husband, who worked as a cabbie, lost his job in July last year. “The owner of the taxi said he would himself drive the taxi, but then I had a tailor shop to feed the family. But that also remains closed due to the lockdown,” bemoaned Basyal, who came to Kathmandu from Sindupalchwok six years ago.

“Last year the Kirtipur Municipality had distributed food but this time they appear indifferent to the sufferings of the people like us,” said Basyal.

When the Post contacted Ramesh Maharjan, the mayor of Kirtipur Municipality, he said his office has no plan to distribute food this time. Instead, he said the city provides work to the needy.

“Anyone in need of work can come to us and we provide Rs 501 for four hours of work,” he said. When the post asked him how many people have benefitted from the scheme, he didn’t have an answer.

Meanwhile, when inquired about the relief package in Lalitpur Metropolitan City, its spokesperson Raju Maharjan said they have not made any decision yet. “Maybe if the lockdown continues then we might bring some relief package for the needy,” said Maharjan.

Similarly, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, which has the largest number of daily wage workers in the Valley, has no plan to provide relief packets to the needy, according to the City’s spokesperson Ishwar Man Dangol.

“We provide work if anyone living in rented rooms came with their landlords’ recommendations. We have a lot of construction work going on within the city right now,” said Dangol.

When asked how many people have been employed under the programme, he had no answer. “None of the wards has received such an application for work. But we can provide work,” said Dangol.

But the poor living in squatter settlements cannot benefit from Dangol’s programme because they cannot produce a landlord's recommendation.

And people like Ganesh Nepali think the Metropolitan City’s work offer is meaningless for many who are infected or too weak to work.

“We are in the middle of a pandemic and there are many people whose entire families are infected with the coronavirus. How can people work in such a situation?” said Nepali.

According to the Nepal Landless Democratic Union Party, there were around 29,000 squatter families in the Kathmandu Valley in 2017. Interestingly, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City does not have data on its poor and vulnerable residents.

It may be recalled that Kathmandu Mayor Bidya Sundar Shakya in an interview with the Post on May 5 had said nobody will have to die of hunger during the lockdown and the needy can visit their ward office for support.

During last year’s lockdown, the City had distributed food relief worth Rs 10.4 million to the poor from all 32 wards. The city had issued funds between Rs200,000 to Rs400,000 based on the size of the population of the wards.

“This time we are not going to do that because the relief was misused. Many people who owned houses in Kathmandu also collected the relief items while the needy were left out,” said Dangol.

Meanwhile, many kind-hearted individuals and groups have been distributing free meals to the needy in Thapathali, Thamel, Pashupati and many other places, just like last year.

Human rights activist and a former member of the National Human Rights Commission, Mohna Ansari thinks food is a basic right of the people and the authorities should provide support to the needy especially during difficult times like these.

“People, especially from the unorganized sector, are facing many hardships as they have lost their sources of income due to the pandemic and the lockdown. The state must support such people,” said Ansari.

27.41°C Kathmandu

27.41°C Kathmandu.jpg)