Theater

Archiving Nepal’s theatrical memory

As Nepal’s theatre culture grows, the absence of a unified archive poses a challenge to preserving its cultural legacy.

Reeva Khanal

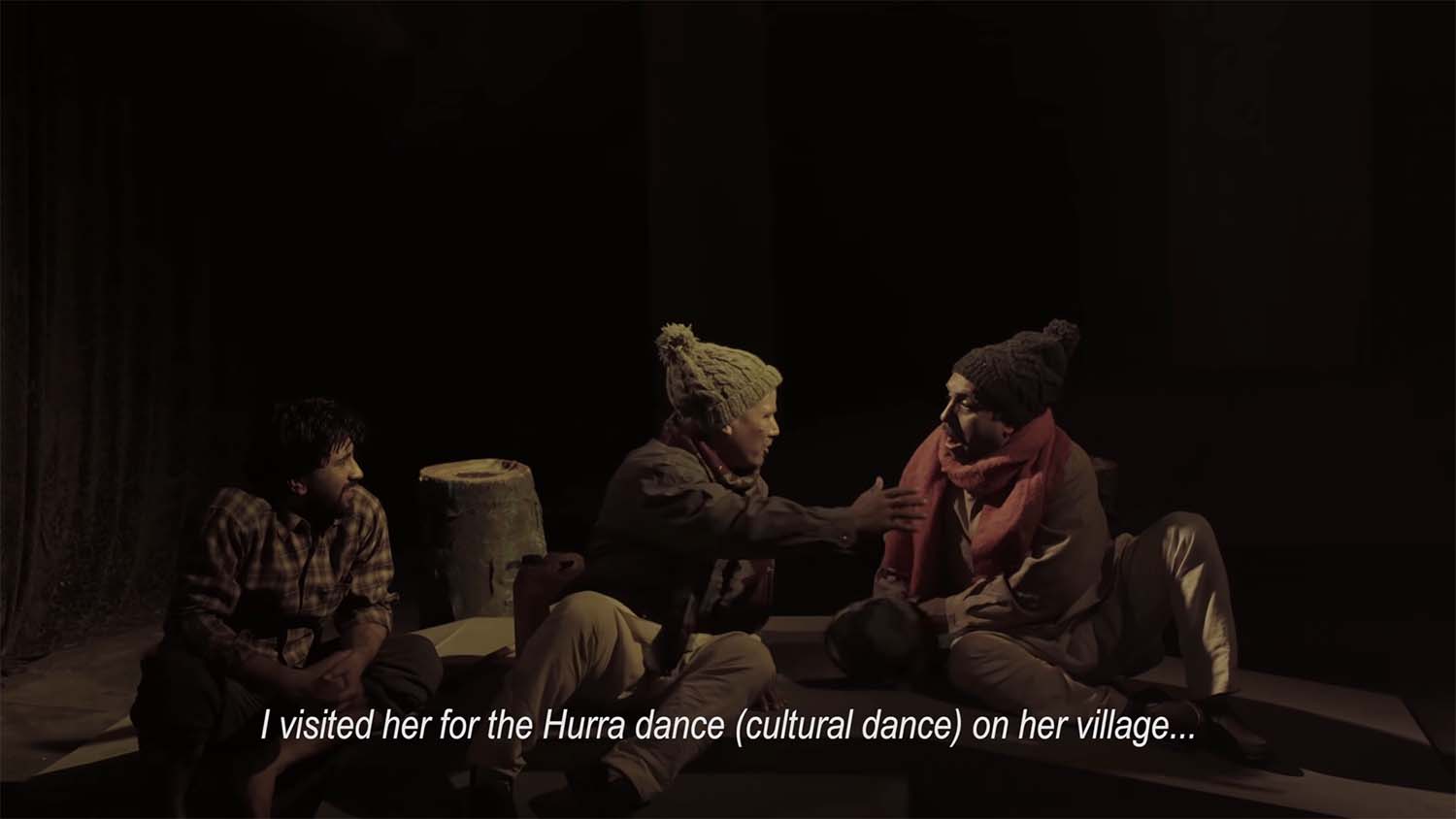

In Nepal, theatre is more than just a craft—it reflects society, memory, and identity. Yet for decades, many stage performances have faded with time, undocumented and forgotten. As the country’s theatre landscape matures, many artists and institutions recognise the need to archive.

From scripts and brochures to entire performances, archiving is emerging as a crucial tool not only for preserving creative work but also for educating future generations and reclaiming cultural narratives. However, this artistic movement faces significant hurdles with limited funding, fragmented efforts, and minimal government support.

Somnath Khanal, co-founder of Mandala Theatre, shares that the Theatre has been actively archiving its productions, albeit in medium quality. “We’ve been preserving not just the recordings of our plays but also the scripts, brochures, and related materials,” he notes. According to him, archiving at Mandala resumed more seriously after 2022. Although the culture of documentation existed earlier—beginning sometime after 2012—it faced a period of discontinuity before being revived in recent years.

He points out that Mandala now has a dedicated department that oversees research, documentation, and archival work. Khanal credits Gurukul as the first institution in Nepal to initiate the process of archiving theatre, particularly folk and traditional forms. “The idea of documentation isn’t new,” he says, “But today’s context demands more—from quality to competitiveness—and that also comes with higher costs.” He believes that financial challenges are one of the reasons why the archival culture struggled to sustain itself consistently.

Khanal stresses the significance of archiving not only for institutional memory but also for artists’ growth. “Watching old performances helps actors learn, reflect and stay motivated,” he explains, highlighting how important it is to be able to study past productions.

On the government’s side, he feels that while institutions like Nepal Pragya Pratishthan are formally tasked with overseeing such cultural preservation, the implementation remains weak. “The actual work is being done by private theatre groups. The government support, at best, feels like a formality,” he observes. According to him, although the state occasionally organises events, its efforts have not translated into a broader impact.

Khanal also reflects on a troubling trend in audience engagement. “People come once, appreciate the play, and never return,” he says, expressing concern over the sustainability of theatre audiences. He believes the lack of effective marketing strategies might be a contributing factor.

As the Academic Director of Mandala Drama School, Khanal links archiving closely with academic development. “Documentation and academia go hand in hand,” he asserts, advocating for formal certification programmes and institutional recognition of theatre as a part of Nepal’s broader art and cultural framework. He argues that academic support can lead to structured research, helping students and aspiring theatre practitioners better understand the field.

With Gurukul no longer in operation, he sees an urgent need for a central institution dedicated to research and documentation in Nepali theatre. “We need a shared space—an academic and archival hub—for the next generation to learn from the past,” he concludes.

Anoop Jyoti Neupane, a theatre artist active in the field for over a decade, shares that theatre groups in Nepal have begun archiving their productions, especially when applying for international festivals or events. He notes that such documentation is important in those contexts and is becoming common.

However, he explains that access to these archives is often limited. Since a play is considered a creative property, whether or not it is shared publicly depends largely on the producer, who has made the primary investment in the production. “If someone approaches with a clear purpose, access is usually granted,” he says, adding that such sharing is more fluid within the theatre community.

He also points out that some plays are available on YouTube, making them accessible to a wider audience. Reflecting on the past, he remarks that due to the lack of proper schooling and technological infrastructure, earlier works were rarely documented. He underlines that theatre is a live art form, best experienced on stage in front of an audience. “When a performance is watched as a video, many elements—especially the real texture—can be lost,” he says.

While some productions today are recorded with digital distribution in mind, he notes that this remains a personal decision made by the director and producer. Overall, he acknowledges that archiving has become more visible in recent years.

Theatre artist and director Pashupati Rai highlights the financial challenges that often accompany the archiving process in Nepal. She points out that since most theatre groups are privately run, there is little to no direct involvement from the government in supporting such efforts. “If the government took this seriously—by encouraging research and involving people in the field—it could lead to broader studies, not just of individual productions but of Nepali theatre as a whole,” she says.

Rai notes that while archiving is happening, it is mostly limited to individual theatre groups documenting their productions. “The process exists, but it’s happening to each group archiving for itself, rather than as part of a unified cultural effort,” she shares. This decentralised model, she argues, limits the reach and impact of archival work. “To build a cultural identity around theatre, these efforts must be connected and recognised at a community or national level.”

She also reflects on the historical invisibility of theatre in Nepal’s recorded cultural memory. “Even during the literary periods, many plays took place inside royal palaces, far from the reach of ordinary people. We still know very little about how theatre was practised, what kinds of stories were told,” she observes. Women, too, were largely excluded from early theatrical spaces, which makes documenting lost or overlooked narratives all the more urgent.

For Rai, archiving and research are inseparable from cultural identity. “Our culture is our identity. To understand today’s society, we must first understand the society of the past,” she emphasises. She advocates for structured workshops, academic involvement, and wider interest in research and writing within the theatre field. “There are some resources,” she adds, “but the foundation still needs strengthening—especially for aspiring artists. Without a stronger base, the larger story of Nepali theatre risks being lost.”

Ghimire Yubaraj, the founder of Shilpee Theatre, underscores the importance of archiving theatrical materials. He shares that at Shilpee, they make a conscious effort to preserve documents, photographs, brochures, and other materials related to their productions. Reviews and critical responses to plays, particularly those published in print media, are also systematically archived. “It’s not just about written records—we’ve maintained a visual archive of both our workshops and performances,” he says. Some of these materials have been made accessible through online platforms, while others are securely backed up digitally for future reference.

However, he believes that institutional archiving alone is not enough. “If archiving is limited to one organisation merely documenting its own productions, it doesn’t serve the broader purpose,” he says. Instead, Shilpee Theatre aims to go beyond internal documentation, committed to preserving a wider range of plays from across Nepal’s theatre landscape.

He explains that the goal is to create a historical record that allows future generations to understand what kinds of theatrical work were being staged years ago and ensures that such cultural memory is not lost over time.

While private theatre groups in Nepal are taking the lead in documenting their work through recordings, scripts, and brochures, these efforts remain individual and decentralised. Artists and directors stress that archiving is not just about preservation but about building a cultural record that informs future generations, encourages research, and deepens artistic practice.

The absence of a unified, national approach to theatre documentation, however, continues to limit its wider impact. Such artistic plays also represent our cultural identity. If nurtured with vision and support, this movement has the potential to safeguard the past and lay the foundation for a richer, more inclusive future for Nepali theatre.

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu