Sudurpaschim Province

Human-animal conflicts rise as development blocks wildlife corridors

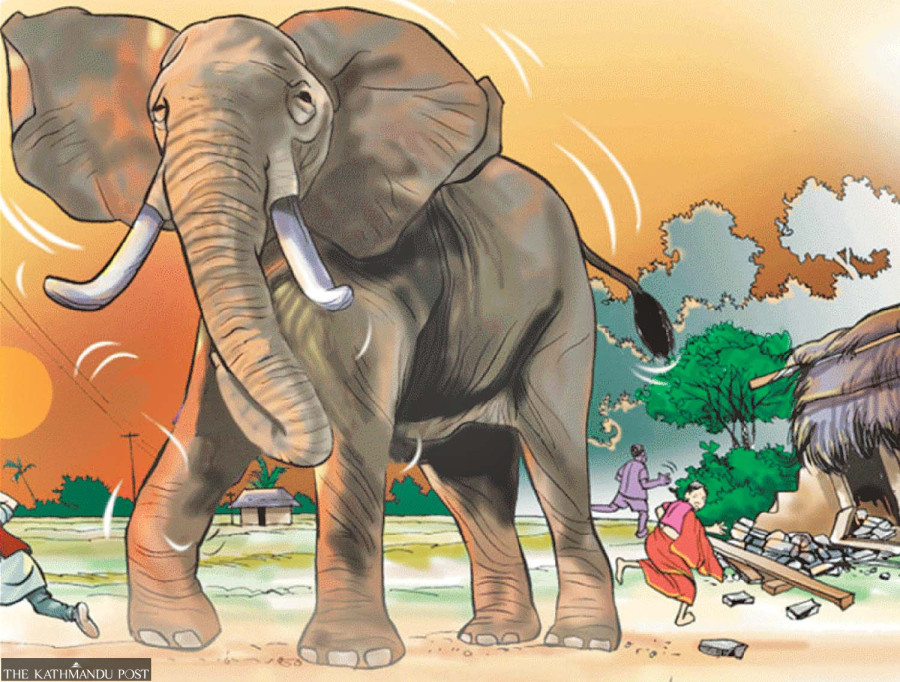

Infrastructure projects like highways and irrigation canals have fragmented key animal corridors in Sudurpaschim province. Three people have died in elephant attacks this year in Kanchanpur district alone.

Bhawani Bhatta

Human-wildlife conflict has been rising in Kanchanpur district, a southwestern Tarai district in Sudurpaschim province, where a series of incidents have taken a toll on both local residents and animals.

Last week, an adult male elephant was found dead near the no-man’s-land area in ward 3 of Dodhara Chandani Municipality. The elephant had reportedly died from an electric shock, with a postmortem confirming electrocution, possibly from an illegal electric trap. Conservation officer Rajesh Lamsal has been assigned to investigate the case further.

Around two months ago, another wild elephant died in a similar incident at Parsiya in ward 4 of Laljhadi Rural Municipality. Although a suspect was arrested for setting an electric trap, the District Government Attorney’s Office did not proceed with prosecution citing insufficient evidence.

These incidents reflect a worrying trend of increasing clashes between humans and wildlife.

Two weeks ago, a tiger that had entered farmland in ward no 2 of Belauri Municipality was captured after two days. The locals were terrorised fearing possible attacks by the big cat. In a similar incident last July, a woman was killed in a tiger attack in ward 2 of Dodhara Chandani Municipality in Kanchanpur.

Experts attribute the rising conflict to disruptions in traditional wildlife corridors. “Elephants require extensive space and follow long migratory routes. With growing settlements and development along these paths, their movement is obstructed, leading to more frequent encounters with humans,” said Purushottam Wagle, a conservation officer at Shuklaphanta National Park.

According to the Division Forest Office in Kanchanpur, three people died and two others were injured in elephant attacks this year alone. Although no official data is available on crop damage, residents frequently report destruction caused by elephants and other wildlife. In buffer zones around Shuklaphanta, wildlife has also attacked livestock and damaged farmland.

Unregulated infrastructure development in and around forested and protected areas is a key factor in blocking wildlife corridors. “Development projects like roads and irrigation canals, as well as expanding settlements are cutting across traditional animal migration routes. These disruptions are fueling conflict,” said Wagle.

Additionally, a steady increase in wildlife populations inside protected areas is forcing animals to venture into human settlements in search of food. The Tarai region, which is home to dense human and wildlife populations, is particularly affected.

“To ensure wildlife can move safely between protected areas, dedicated corridors must be preserved. These corridors not only support gene flow but also help prevent species extinction during epidemics,” said Rambichari Thakur, chief of the Division Forest Office.

Unfortunately, in Nepal such corridors are increasingly being compromised. Shuklaphanta National Park is now fragmented by the Mahakali Irrigation Project, the East-West Highway and the Kaluwapur-Belauri road. Similarly, the Laljhadi-Mohana corridor, once a key route connecting India’s Dudhwa National Park through the Chure hills to Shuklaphanta and back, is now heavily obstructed.

The traditional elephant route that extends from Nepal’s Chure section to Brahmadev, crosses the Mahakali river and reaches India’s Nandhaur Wildlife Sanctuary, has also been disrupted at multiple points. These blockages, according to the conservationists, have forced elephants and other wildlife into nearby human settlements, heightening the risk of conflict.

Two years ago, an adult elephant died after getting trapped in a septic tank near a community forest office in Shuklaphanta Municipality. “Even elephants from India’s Dudhwa National Park are now staying longer in Shuklaphanta,” said Wagle. “As they enter villages in search of food the likelihood of conflict rises.”

Conservationists warn that unless traditional corridors are urgently restored and managed, human-wildlife conflict will intensify further and could spiral out of control. They stress the need for restricting large-scale infrastructure projects within or near protected areas and ensuring wildlife movement is prioritised in development planning.

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu