Bagmati Province

In Chitwan, unchecked human-wildlife conflict adds to conservation challenges

Better habitat management, timely identification of problematic animals and increased community engagement are key for conflict control, experts say.

Ramesh Kumar Paudel

The Chitwan National Park—home to rare one-horned rhinoceros, tigers, gharials, and wild elephants, among others—has long been a symbol of Nepal’s conservation success. But the unchecked human-animal conflict in the park and its vicinity has resulted in tragic consequences.

According to park data, a total of 127 people have lost their lives in wildlife attacks in the area over the past 11 and half years, making human-wildlife conflict a pressing issue in the region.

Wildlife attacks have been a persistent challenge for the communities surrounding the Chitwan National Park. Among the animals responsible for these fatalities, rhinos have claimed the highest number of lives, followed by tigers and wild elephants. According to official reports, rhino attacks have led to 52 deaths, tiger attacks have claimed 40 lives, and wild elephants have been responsible for 28 deaths in the past decade.

The presence of wild elephants near human settlements is particularly concerning. Male elephants from the park often venture into nearby villages, attracted by domestic female elephants. These elephants cause significant destruction by consuming crops and even raiding households for food and salt.

One such notorious elephant, called Govinde, has been responsible for multiple attacks. In October last year, it killed a 40-year-old employee of the Elephant Breeding Centre in Khorsor, Sauraha.

Rhinos, which were once on the brink of extinction due to poaching, have seen a significant increase in their numbers due to conservation efforts. However, as their population grows, so do human-wildlife conflicts. In January this year, a rhino attacked and killed 70-year-old Krishna Kumari Thapa in Ratnanagar Municipality-16. Five others were injured in the same incident.

Chitwan National Park has the highest tiger population in Nepal. While the number of tigers has increased due to strict conservation measures, so have the risks associated with human encounters. Tiger attacks fluctuate yearly, with some years seeing multiple fatalities and others reporting none.

In July 2023, 35-year-old Anil Tamang from Khairahani Municipality-12 lost his life in a tiger attack. Later, in December same year, two men from Rautahat district were killed by a tiger while they were collecting grass in a nearby forest.

Wildlife researcher Baburam Lamichhane, who has conducted extensive studies on human-tiger interactions, suggests that only about five percent of the tiger population is responsible for human attacks. “Identifying and monitoring these problematic tigers can help mitigate conflicts,” Lamichhane said. “If necessary, such tigers should be relocated or kept in enclosures.”

Currently, seven tigers have been kept in captivity in Chitwan due to their repeated involvement in attacks. Another was recently transferred to Parsa National Park due to a lack of space in Chitwan’s enclosures.

The Chitwan National Park, along with government agencies and conservation organisations, has been working on multiple strategies to minimise human-wildlife conflict. These efforts include electric fencing, awareness campaigns, and compensation programmes for victims’ families.

Ganesh Panta, chief conservation officer of the Chitwan National Park, acknowledges the challenges in managing wildlife populations within park boundaries. “The idea of keeping all wild animals inside the park sounds simple but it requires extensive habitat management,” Panta said. “Our resources are limited but we are doing our best.”

One of the significant reasons for increasing rhino encroachments into human settlements is the deterioration of grassland habitats inside the park. In the past, about 20 percent of Chitwan National Park was covered in grasslands. This has now come down to around 10 percent, forcing rhinos to venture outside in search of food. Although there have been efforts to restore grasslands, the allocated budget for such initiatives has been shrinking. In the fiscal year 2016-17, approximately Rs32 million was allocated for grassland management, but this has dwindled to just Rs3.7 million in the current fiscal year of 2024-25.

Local communities play a crucial role in addressing human-wildlife conflict. The buffer zone community forest users’ committees, which oversee conservation efforts in the park’s surrounding areas, have been implementing various preventive measures.

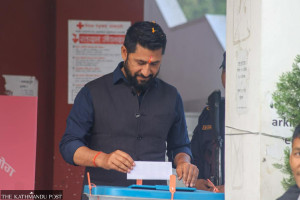

In Madi Municipality, one of the high-risk areas, electric fencing and concrete barriers have been installed to deter wildlife from entering villages. As a result, incidents have gradually declined. However, community leaders argue that more needs to be done. Ram Lal Mahato, a former member of the Bagmati Provincial Assembly and a long-time conservation advocate, says new approaches are necessary. “Conservation efforts have been significant but human casualties continue,” Mahato said. “We need to rethink our strategies and ensure that wildlife stays within the park.”

Mahato also emphasised the need for sustainable financial support for affected families. In the past, compensation for wildlife attack victims was minimal. Now, families receive up to Rs1 million, and medical treatment for injured victims is fully covered. “If we can continuously improve these support systems while enhancing wildlife management, we can create a safer environment for both humans and animals,” Mahato added.

Experts suggest that addressing human-wildlife conflict requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes better habitat management, timely identification of problematic animals and increased community engagement. Moreover, strict enforcement of conservation policies, coupled with innovative solutions such as wildlife corridors and improved fencing, can help reduce encounters between humans and dangerous wildlife.

Chitwan National Park is the major habitat of tigers, rhinos and several other endangered species in Nepal. There has been a rise in the population of both tigers and rhinos in the national park and its vicinity.

One-horned rhino, which is native to Nepal and India, is an endangered animal. Nepal is home to 752 one-horned rhinos and Chitwan National Park alone has 694, according to the national rhino census conducted in 2021. The 2015 count had found 605 rhinos in the park.

According to the latest tiger census held in 2021, the tiger population in Nepal has reached 355, with the country nearly tripling the number in 12 years. Chitwan is a major habitat for tigers hosting as many as 128 big cats in its forests and surrounding areas. In 2018, Chitwan National Park was home to 93 tigers.

13.31°C Kathmandu

13.31°C Kathmandu1.jpg)