Madhesh Province

Complexity of transgender life in Janakpur

In addition to facing discrimination in public spaces and government institutions, they are often subjected to physical and sexual harassment.

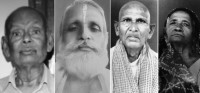

Aarati Ray

In a rented four-room flat in Pidari Chowk, Janakpur, nine people live rather challenging lives due to their identities in a heteronormative world.

These nine individuals share no biological ties, come from different castes and religions. Yet their bond is deeper than family—they follow the system of “hijra gharana.”

Tabu Khan, 27, is one such member. Though Khan is a Muslim, she lives harmoniously in the gharana, where religious and cultural diversity coexist under the guidance of 56-year-old Pawan Kali Yadav, known as ‘Guru Mai’ by the group.

The ‘hijra gharana’ forms a non-heteronormative kinship structure, operating through a discipleship-lineage system. Through ritualistic ceremonies, a guru adopts a ‘hijra’, or ‘chela’, creating a nonbinary family network.

While they adhere to the ‘hijra kinship’ model, Malti Mahaset, 45, says, “Though we embrace the ‘hijra gharana’ system and profession, many in our group, including myself, prefer not to be labeled as ‘hijra/kinnar’. These terms are often used derogatorily against us, so ‘third gender’ or ‘trans’ feels more respectful.”

She adds, “It ultimately depends on personal preference; not everyone avoids these terms.”

This gharana primarily relies on income from ‘badhai’—traditional dances performed at weddings, childbirths, and festivals, where they bestow blessings on families in Nepal and India.

Yadav said they also engage in ‘challa maga’ (a form of begging in public spaces).

“When we go for ‘challa maga,’ people often give us coins and ask us to bless their gold or silver,” says Roshni Ray, a resident of Janakpur sub-metropolis’s ward 14.

Some even invite them to their homes for blessings, treating them with respect. During ‘badhai,’ they receive similar respect, as many believe the blessings from trans communities are auspicious.

“People respect us only when they need blessings,” Ray, 28, says. “They invite us to ceremonies but turn away afterward. We’re seen as good luck charms, not as equal humans.”

Despite some improved recognition and respect from family and society, their access to healthcare remains dire and inhumane.

Khan describes their treatment at Janakpur Provincial Hospital as “worse than given to animals.”

When she visited the hospital six months ago for a syphilis injection, she was ridiculed by the staff. “The doctors treated me like an animal in a zoo,” she says. “They asked about my issue in front of a crowd, made crude remarks about people like us and humiliated me by asking me to lift my sari for the injection in front of everyone.”

Manisha Shah, 27, had a similar experience. According to Shah, in the hospital, staff are often rude and ask them to sit separately from the general line, as if they are ‘dirty evil things.’

“We depend on government hospitals since we can’t afford private care, but even there, we don’t get adequate treatment,” added Shah. “When we file complaints with the District Police, they often mock us, and some go so far as to say, ‘Come meet me at night, and then I’ll help you’.”

In addition to facing discrimination in public spaces and government institutions, they are often subjugated to physical and sexual harassment.

Six days ago, while returning home from the market in Barbigha Ground, Khan was cornered by four boys and molested.

“It’s true that some in our community engage in sex work, but that’s their choice,” Khan said. “But that in no way gives others a right to violate us. Even if I were a prostitute, nobody could touch me without my consent… But we are often treated like objects. I completely froze during that incident. But this was not the first time I had been subjected to incidents like this. I had been raped three years ago.”

After the incident, she went to the provincial hospital for treatment of her injuries. “Anyone could see what I had gone through, yet the nurse kept saying, ‘Why do you people engage in these things for money?’ while treating my wounds,” Khan adds.

“Harassment and rape have become so common that we’ve grown numb to them,” another 25 year old trans woman Puja said, showing the injury around her neck that resulted from the harassment that she faced a month ago.

For the gharana, in a society that seldom accepts them, organisations like Sunaulo Bihani Samaj offer comfort by advocating for their rights and encouraging them to speak up.

However, Puja says, “Where is the government? Why are hospitals and police stations still so unwelcoming?”

Aside from doing ‘badhai’ and ‘challa maga’, they are also famous as ‘natuwas’, performers invited to dance at festivals like Holi and Chhath. For many, including Puja, these performances provide a livelihood. “As a natuwa, I get to dance and express myself beautifully,” she says.

However, the path to earnings is not without challenges.

While trans individuals are celebrated as entertainers, they often face objectification and ridicule. Puja says that during performances, some make vile comments and invade their personal space, even entering their makeup rooms.

They rarely get the promised full payment. The payment for performances often depends on youth and beauty, leaving older members of the community at a disadvantage.

“As we age, we’re less likely to be hired,” said Muskan Sahiba, another member of the community. “So we younger ones share our earnings with older members, or our ‘Guru’, as a way of supporting those who no longer have a way to earn or family to rely on.”

Since earnings in Nepal are hardly enough, they often travel to India for ‘badhai’ and ‘challa maga’. When in India, they live in ghetto communities of Mumbai and Patna.

Despite facing some mistreatment, the support from ‘hijra gharanas’ in India keeps them going. Khan, the only Nepali trans individual from their gharana in Patna, says, “Here, they call me ‘beti’ [daughter] and love me. This support within our community is the shield from external hate.”

However, the instances of trans community being murdered and raped in Patna and Mumbai keeps them on their toes.

Nepal too is unsafe. Many like Mahaseth face harassment while walking through the roads and markets of Janakpur. Police often threaten to arrest them, assuming they are begging or engaging in prostitution, and sometimes even resort to violence.

Mahaseth says, “Nobody wants to beg for a living; we want to work, but no one offers us jobs. The government provides jobs for men and women—why not for us? We’re not asking for high-profile positions; I can do cleaning or cooking.”

Satya Narayan Shah from the Sunaulo Bihani Samaj, a sister organisation of the Blue Diamond Society in Janakpur, says they connect around 3,000 queer people in the Dhanusha district and conduct sensitisation programmes for hospitals and police.

“While we’ve seen some improvements, changing people’s mindsets is still a challenge,” Shah adds. Hate crimes, including rape and physical abuse, are common, with many perpetrators going unpunished.

For the trans community of Madhesh, the roles they perform—whether as natuwas in local festivals or performing badhai and challa maga in Indian cities—are essential to their survival.

But these roles are also traps, perpetuating their status as outsiders. “We’re tired of being treated like objects of entertainment or like something to be feared under the guise of respect,” says the ‘guru mai’ Yadav.

Their fight is not just for economic stability but for dignity. “I want to work and live a normal life, but no one gives us that chance,” Khan adds. “Why, because we are different?”

The community’s demands are simple: respect, safety, and the right to live as equals. But even these basic demands remain unmet.

“We need systemic changes that grant us the rights and dignity we have long been denied,” Puja says.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu