Opinion

No longer a yam?

Will Nepal develop an alternative vision for connectivity if the trans-Himalayan economic corridor doesn’t work out?

Amish Raj Mulmi

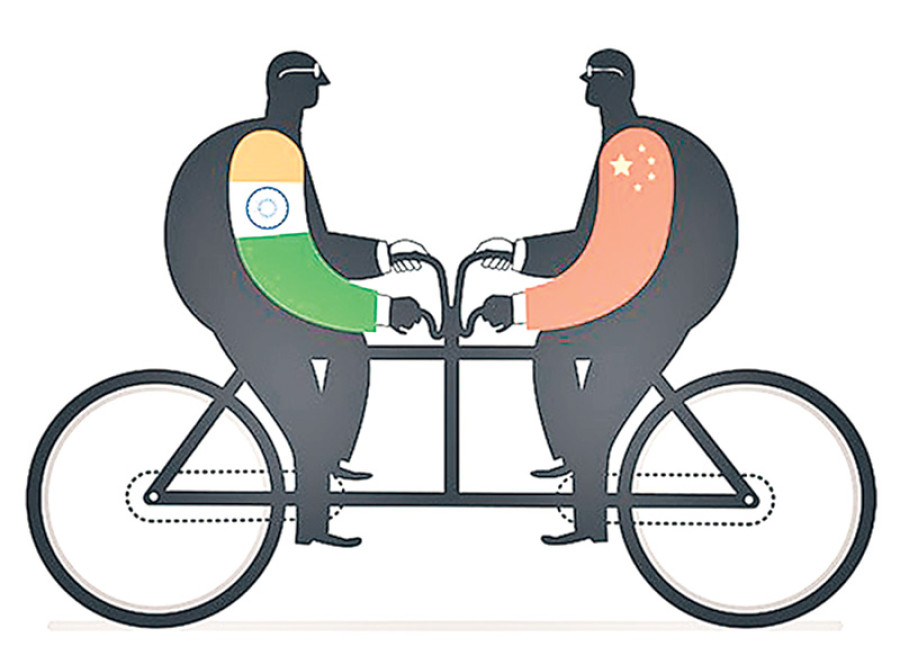

There’s a phrase that’s been doing the rounds as panacea to Nepali foreign policy once again—‘trilateral cooperation’: a utopic scenario where Nepal finds itself taking advantage of the massive economies of China and India to be a conduit for trade between the two countries. Calls for this have gained momentum after Nepali foreign minister PradeepGyawali’s visit to China, where Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi said the three countries were ‘natural friends and partners’, and insisted China’s trans-Himalayan connectivity vision ‘can also provide conditions for an economic corridor’ connecting the three nations.

The Nepali establishment is, for obvious reasons, encouraged by such calls. Oli has pushed forth a vision of neutrality between the two neighbours, and he has sought to convince India that an expanding Chinese imprint in Nepal will not harm Indian interests. One can reasonably ascertain discussions around a trilateral corridor will feature during Indian PM NarendraModi’s visit next week, who has himself recently returned from an informal meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping.

India and China are attempting to reach a common ground of shared interests, beyond existing border disputes, to reach what an Indian analyst has called the long-term goal of ‘set[ting] their respective growth trajectories...to create synergy instead of crossing each other in the Indo-Pacific region.’ The two nations are aware that there are core differences—China’s support to Pakistan, India’s alignment with the US and Japan, and long-standing border disputes with the potential to flare up into delicate situations like last year’s Doklam stand-off—but there remains an active channel of communication from both sides, peaking with the informal meeting, the 11th such meeting, between the two heads of state. The two nations issued a ‘strategic guidance’ to their respective militaries to ‘build trust and mutual understanding and “enhance predictability” and “effectiveness” in managing border affairs’, while also seeking to deepen bilateral ties and strengthen ‘strategic communication’.

At the same time, India is wary at the proposed trans-Himalayan economic corridor, just like it is with other Chinese investments in the subcontinent. Indian analysts have called it a political statement that will not bring many economic benefits. And although it would like increased economic cooperation and trade with China, there are also far too many security issues within the subcontinent for India to be comfortable with a Chinese rail link through Nepal. Despite the many overtures between the two sides, Doklam remains fresh on their mind. The Indian media has suggested Modi will make India’s stand on the issue clear during his Nepal visit; India is more keen to work on bilateral infrastructure or development projects in Nepal, and ‘not through any mechanism involving a third country’.

Trade as a driver

The modern-day Indo-China relationship hinges on several factors beyond the disputed border. Indian policy analysts increasingly point to China’s increased investments in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), such as the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka and the Chinese Navy’s military base in Djibouti, as signs that it wants to expand its footprint in the IOR with or without India. A recent report by a US-based think-tank, ‘Harboured Ambitions’, argued that ‘Beijing is molding the Indo-Pacific to ensure its national security interests are adequately protected through the development of commercial ports that can facilitate long-range military patrols and investments that can generate political goodwill or—when necessary—coercive power’. India and China also have differences over China’s unwillingness to support India’s entry into the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group, and India’s attempts to notify Pakistani terror group Jaish-e-Mohammed’s leader MasoodAzhar as a UN-designated terrorist.

At the same time, there are also increasing convergences, particularly in an era where Trump has withdrawn the US into protecting its own interests, and where China finds it more advantageous to seek out alternative markets for its products. ‘Beijing now faces tariffs on $150 billion worth of products, though it has announced counter-duties, there are limits to what it can do for the simple reason that it imports far less from the US than it exports. US exports to China are just $130 billion while the US imports $506 billion worth of goods,’ wrote the analyst.

India remains China’s best alternative market to the US. It’s currently growing faster than China, and bilateral trade between the two nations rose to $84.44 billion in 2017, growing by 18.6 percent. The trade, heavily skewed in favour of China, means it will seek to leverage the Indian domestic demand, and strive to have India on its side in the event of a Sino-US trade war. ‘The recent China-US trade conflict and the US one-sided ban of China's ZTE Corp remind China, India and other countries with dreams of rejuvenation that China and India still need strategic unity in order to reshape the old international political and economic order,’ an oped in Chinese state-approved media outlet Global Times argued, while another oped in the same paper said, ‘They both have to strive for the right to develop and face Western pressure on issues like trade and intellectual property rights.’

The Nepali alternative

Although Nepal-India ties are important, and an economically dominant China has allowed Nepal to hedge its bets against India, Indo-China ties will continue to deepen even without a trilateral relationship with Nepal. A trans-Himalayan economic corridor, the bilateral visits between Modi and Xi, and India’s red-carpet treatment to Oli—all of these need to be seen against the increased rapprochement between India and China, and the convergence over issues of trade. So when a Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ says, ‘In my discussions with Modi and Jinping, I’ve repeatedly told them that if they grow without incorporating Nepal in their development, their growth will be an incomplete one [translation mine]’, it may be music to our ears, but is a view that veers into the territory of fantasy. The economic relationship between India and China is far too entrenched for both countries to depend solely on a trans-Himalayan corridor.

Can Nepal then develop an alternative vision in the eventuality of India not agreeing to a trilateral economic corridor? A correlated query would be, will China then find it economically feasible to only link Lhasa to Kathmandu? At the same time, will the infrastructural links be restricted to trade, or will it also foster people-to-people movement? For, the question then arises, would China be willing to open up Tibet to the world via Nepal? And as Indo-China ties improve to a point of convergence, can Nepal then afford to play the China card against India?

These are questions Nepali policymakers must think about. While the vision of a trans-Himalayan economic corridor with rail and road links from Lhasa to Lucknow via Kathmandu is an ideal scenario that our politicos can sell to the electorate, there is an equal, perhaps greater, possibility this will not occur as part of an idyllic vision of China-Nepal-India cooperation. If anything, Nepal should be prepared with an alternative to this vision, wherein our geopolitical location can drive through other advantages.

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)