Opinion

Trending: blending

Blended finance scales up at the right time for Nepal

Tim Gocher

On the snow-covered streets of Davos, Switzerland this year, participants struggled for the first time in the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) 48-years history to make the opening session on time. Due to extreme weather, VIPs who normally arrive by private jets or chauffeured limousines, joined the crowded trains with other delegates.

This year, blended finance took centre state. Blended finance uses public or donor capital to increase investment by the private sector to fill funding gaps in Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in infrastructure and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

That gap is vast. According to UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2014, LDCs need $120 billion per year to meet SDG targets—$80 billion short of current, annual investment levels. The same report estimates total investment needs in LDC’s of $1.8 trillion for the period 2015-2030.

In Nepal, the Finance Minister has stated that the country needs $6 billion annually in infrastructure investment, of which the private sector contribution will need to be $4-5 billion. As the available domestic capital is a long way short of this, most will need to come through Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). According to the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), FDI in the fiscal year 2016/17 was just $78 million. Only international private sector investors, with $1.8 trillion already allocated to infrastructure in low and middle-income countries, can fill this gap. Nepal’s power sector alone will need at least $10 billion in addition to local capital to meet the Ministry of Energy’s baseline installed capacity requirement of 8,937 MW by 2030.

Why don’t large international investors invest much in Nepal?

Often, LDC investments have the potential to generate higher returns than those in developed markets. So why aren’t large international investors investing much in countries like Nepal? The answer is risk. International investors have a fiduciary duty to manage their funds carefully which means not taking too much risk. Here are some examples.

As Standard Chartered Nepal CEO Joseph Silvanus’ article pointed out last week, Nepal is the only country in the South Asian neighbourhood (except Afghanistan) without a sovereign credit rating. This is the metric by which the world judges credit risk. International investors see the lack of a formal rating, assume the worst and charge a premium that is not economically viable. The reality of risk on the ground may be different. With the government’s 100 percent payment track record on PPAs, and healthy foreign exchange reserves, it is likely that a Nepal sovereign rating would be better than what international investors expect.

Another example is currency risk. Nepal must manage its foreign exchange reserves carefully, and is understandably cautious about offering US dollar payments. But without them, international investors are at risk of both Indian rupee volatility and a potential peg adjustment. In Nepal, we may not perceive the latter as a high risk, but over say 25 years of a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), international investors are more nervous and have been stung in the past by catastrophic currency adjustments.

The above examples are before the perception of political instability, complex bureaucracy and earthquakes are factored into risk. The truth is that even if Nepal were to offer extremely high returns in US Dollars (which would be economically and politically difficult), the country is often seen as so risky that large international investors may still not be prepared to enter. The largest funds, which include pension and insurance funds managed out of the world’s financial centres, are simply not permitted to take that much (perceived) risk with their policyholders’ funds. They are investing heavily in India and China, but Nepal and many other LDCs are off the menu. This partly explains why FDI to Nepal is so small, $3.66 per capita, compared to that of Bangladesh ($11.7), Pakistan ($12.03), India ($33.6) and Sri Lanka ($42.36).

How can blended finance help?

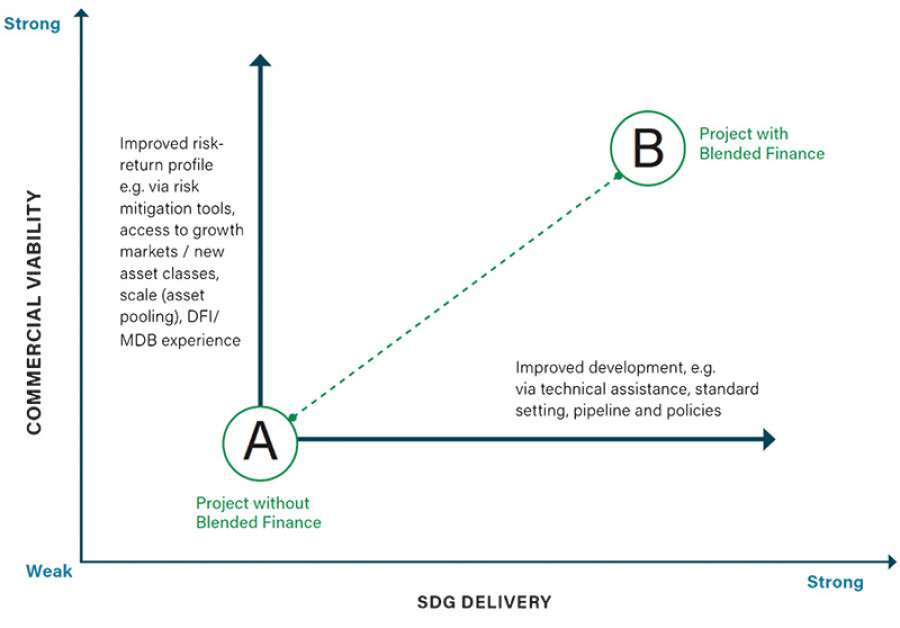

Yet there are plenty of reasons for optimism. Blended finance “crowds in” private sector capital into otherwise commercially unattractive projects to achieve a balanced risk-return profile. For example, TCX—an exotic currency hedging firm established by FMO and partners with public funds—can hedge the Nepali rupee against the US dollar. MIGA (part of the World Bank) can insure investors against sovereign credit and other political risk. And other public institutions are developing tools such as grants, “first loss” capital and guarantees that can soak up an element of loss should it occur, before private sector investors are hit.

This wave of blended finance availability comes at a time of relative political stability in Nepal following the considerable achievement of the constitution’s implementation and the election of a majority government. Never has there been a better time for Nepal to utilise this capital to get the investment it needs. Blended finance structures typically mobilise $3 of commercial finance for every $1 of public capital, compared to the aggregate mobilisation by Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) on an institutional level, which is less than 1:1.

Instruments used to achieve these results are designed to offset a number of perceived investor risks. These include political risk, currency volatility, credit risk, lack of liquidity, weak local financial markets, knowledge gaps about investment opportunities, and challenging investment climates including poor regulatory and legal frameworks.

Government access to blended finance

Blended finance tools are not limited to private investors, nor should they be. The government is in a good position to access these tools available from publicly-funded groups such as World Bank, Green Climate Fund, TCX, GuarantCo and many others. This would enable them to pass the risk reduction through to the private sector—for example offering US dollar payments, a World Bank guarantee in the event of non-payment, and cover or limited losses due to delay. This will not only stimulate international capital, but should also trigger growth in domestic investment. And beyond infrastructure, tools are available to increase private sector financing for small and medium size enterprises (SMEs).

Blended finance is scaling up at the right time for Nepal, alongside political achievements and China’s Belt and Road Initiative. It should not, however, be seen as a permanent solution. As Nepal attracts international investors, and if those projects are successful and rewarding, in the long run the international investment community’s perception of Nepal’s risk will reduce, lowering the cost of capital and hopefully making blended finance obsolete.

Attendees at this Friday’s Blended Finance Conference in Kathmandu include some of the names above, and Allianz—the insurance giant with €2 trillion of assets under management. They won’t have the snow to fret over, but will instead need to think constructively about ways Nepal can tap into the $50+ billion blended finance market to bridge its infrastructure and corporate funding gap.

Gocher is CEO of Dolma Impact Fund

23.51°C Kathmandu

23.51°C Kathmandu