Opinion

An unfinished agenda

We need to rethink the influence gender biased mythology plays on our treatment of women and girls

Bhawana Upadhyay

The recent Durbarmarg gang rape case made many of us furious. Mohna Ansari’s initiative in issuing a statement about Nepal Police’s negligence in registering and investigating the case was commendable. Following the failure of the police administration to register the victim’s complaint against the perpetrators, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has formed its own investigation panel.

Headlines related to gender based violence seem to dominate the media at present. Fresh news of acts of violence against women at varying scales receive coverage almost every day. “Despite a

public outcry and rage expressed on social media, a majority of the perpetrators still remain at large”, says a lawyer friend of mine who has been dealing with sexual crime cases for more than a decade now. Recently, she shared a story of a 16 year old girl who had been repeatedly molested by her uncle for the past five years.

The girl was told to remain silent by her mother. The uncle is a Hindu cleric. After the demise of the girl’s father, this cleric had been exploiting his niece secretly under the guise of a benevolent guardian. There are many such occurrences where family members of victims try to conceal such crimes due to fear of further oppression. This fear has undoubtedly been fuelled by social pressure.

My brief exchange with this lawyer friend actually led to a lengthy conversation about our cultural practices and the socialisation process.

Femininity and mythology

Commentary on Hindu mythological stories still intrigues me. Though these stories are extremely difficult to validate, they help in exploring masculinity and femininity through male and female mythical characters. They provide an interesting perspective on how our society has evolved, if one could trace these stories systematically.

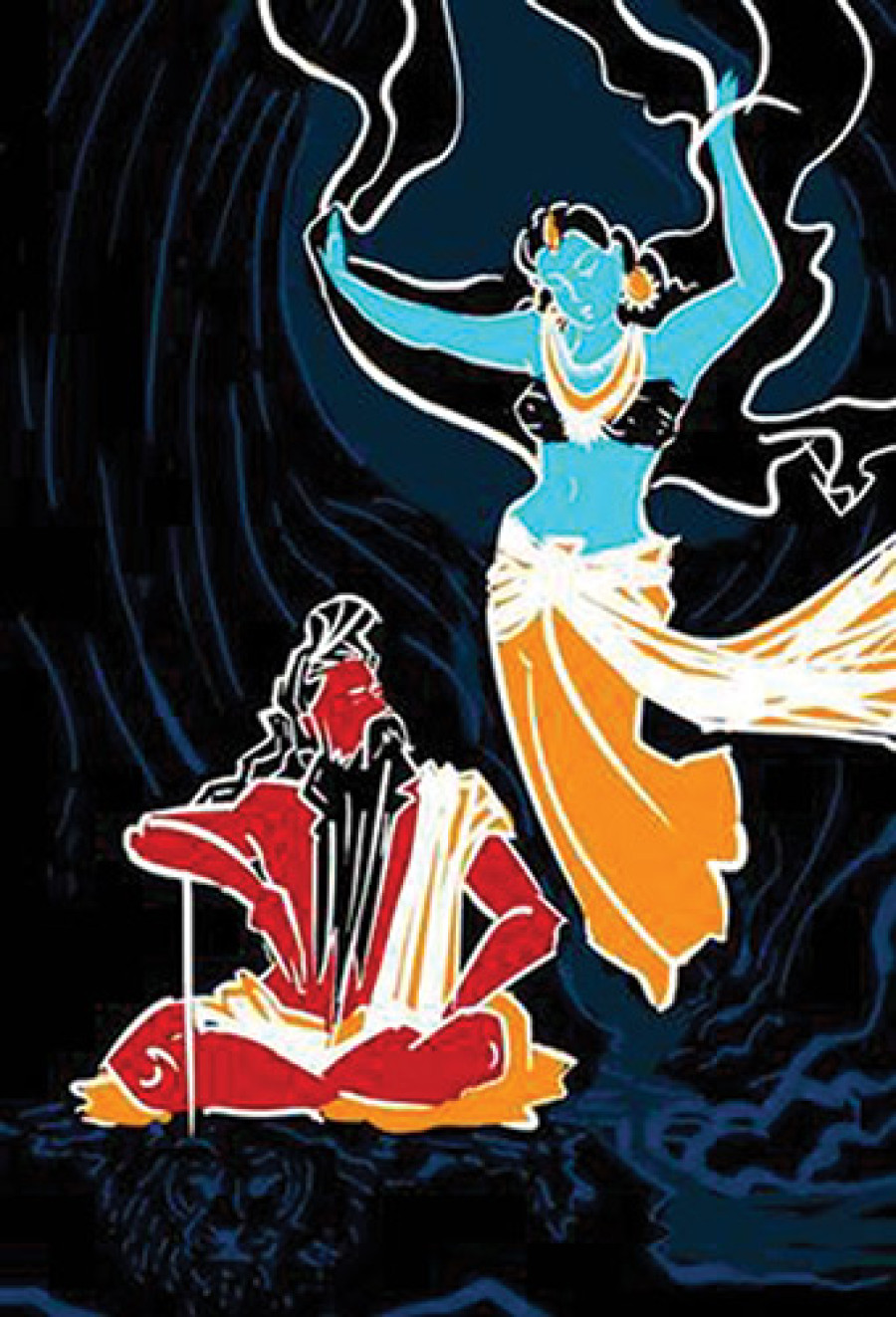

These stories often depict women in a paradoxical way. On the one hand, female characters are portrayed as timid and always seeking protection from their male kin. On the other, they are described as those who limit men’s pursuit of power and prestige. Apsara Menaka and sage Vishwamitra’s story is a good example, wherein Menaka was accused of curbing Vishwamitra’s growing spiritual power. But, Indra’s trick of sending Menaka to seduce Vishwamitra using the support of the god of winds, Vayudev, is never questioned. We seem to either overlook or forgive Indra’s hidden motive.

The story goes that Indra (the king of the gods) was insecure of the growing power of Vishwamitra, who was acquiring power through ascetic practice. Menaka entered the place where Vishwamitra was in a state of meditation, and Vayudev blew and lifted her garments up to expose her privates. When Vishwamitra opened his eyes, he saw the beautiful Menaka and dropped his ascetic practice to make love to her. This is just one example that depicts how the mythical stories help reinforce the patriarchal framework: accusing women of using their sexuality to entrap or destroy men. There are many such stories in Hindu mythology that have portrayed female characters in such a way.

Relevance to modern times

The portrayal of these characters in this way seems to have been ingrained into our modern minds. From a primitive time—when we were hunters and gatherers—gender roles and norms were defined on the basis of a patriarchal model. What I abhor is that these roles are being religiously practiced in South Asia till date. Notably, such practices are scanty in many South East Asian countries.

Most of the family customs in South Asia underscore masculine cultures that socially produce biases against women in all spheres of human development. Gender inequality exists in our modern homes because we are still unable to let go of the idea of liability. In our society, daughters are still considered as liablities to their parents. This notion of liability, and the preference for a son as a family asset, has taken away all the respect for girls and women in our culture.

If this mind-set of differentiation along gender lines continues to exist in our societies, violence against women is not going to end. This mindset speaks of how we, as a society, have allowed ourselves to develop.

It is time to reflect and question ourselves about whether, as a society, we have subconsciously been following these mythical stories to justify violence against women in reality. Such reflections demand a greater responsibility from families to critically examine the kind of religious customs, prejudices and cultural beliefs they are nurturing.

What we need is education in society as a long term solution. Education will help to challenge the prevailing gender prejudices in households. This will help Nepalis to critically examine their thinking. As Socrates rightly said, an unexamined life is not worth living.

- Upadhyay writes on social and sustainable development issues

13.68°C Kathmandu

13.68°C Kathmandu