Opinion

Justice delayed and denied

Many more cases like Dhungel’s will have to be brought to justice before some kind of normalcy returns

Deepak Thapa

Wit parliamentary and provincial elections looming on the near horizon, the country is beginning to get a sense that the long period of political transition is finally coming to an end. And, kudos to everyone who managed to steer our country, after a fashion, during this very unstable period, by, first, not allowing the peace process to break down, and despite ominous portents in the earlier years, without a relapse to any kind of large-scale political violence. But the one major issue remaining is that of transitional justice. On that score, the political process has thoroughly failed the victims of the conflict.

The arrest a couple of days ago of former Maoist lawmaker, Bal Krishna Dhungel, will hopefully bring the spotlight back to this crucial, and largely ignored, aspect of the peace process. Dhungel’s claim that his arrest will complicate the transition to peace is beginning to look thin, with his own party only coming up with a half-hearted statement repeating the same thing.

More shallow has been Dhungel’s stance that the execution-style murder of one Ujjan Shrestha in 1998, which he does not seem to dispute, was a political act. From all accounts, the only crime Shrestha appears to have committed was of being a philanderer, a Casanova, or what in common parlance would be known as a ‘fast guy’. Serious enough in the eyes of the supposedly puritanical Maoists, but certainly not so grave as to warrant an arbitrary death sentence considering that at least two of their top leaders are known to have been disciplined for sexual transgressions in the past, and they continue to enjoy high office, quite alive.

Senseless killings

I made about half a dozen trips to the conflict areas when the fighting was going on, and everywhere I went it was the same sorrow that greeted us. In Bajura, while the filming of the documentary, Six Stories, was going on, I had to ask director Mohan Mainali to excuse me and ran away from listening in as the wife of someone most inhumanely killed by Nepal Army soldiers painfully recounted that day in all its details. Another difficult instance was interviewing of the wife of Mukti Nath Adhikari, the Lamjung school headmaster, whose murder made international headlines. But, most disturbing for me personally was when I went to Chisapani in Khotang.

On the same day as Adhikari was killed, January 16 2002, on the other side of the country, high up in the very picturesque mountaintop village of Chisapani, another teacher had been killed. Headmaster Harka Bahadur Rai had fallen foul of the Maoist-affiliate Khambuwan National Liberation Front, a group that was meant to safeguard the rights of the Rais, and for that he paid with his life. Given Chisapani’s remoteness, news of Rai’s murder reached the outside world only a day later and was completely overshadowed by the killing in Lamjung, which flashed around the world with the photograph of Adhikari’s kneeling body tied to a tree and a puncture mark just under his heart.

Nearly a year later, terror struck the same school Rai had headed when Hari Prasad Bhattarai, a well-liked teacher, was killed by soldiers from the Nepal Army. It was around three weeks later that I arrived in Chisapani as part of a National Human Rights Commission team to investigate that killing. The emotions become raw again as I remember the courtyard formed by Bhattarai’s two houses and his two wives in mourning white, hardly able to respond to our queries. We saw Bhattarai’s bedroom festooned with a poster of Marx, but as we had been told that he was a UML sympathiser, it was only but natural to have such a portrait at home.

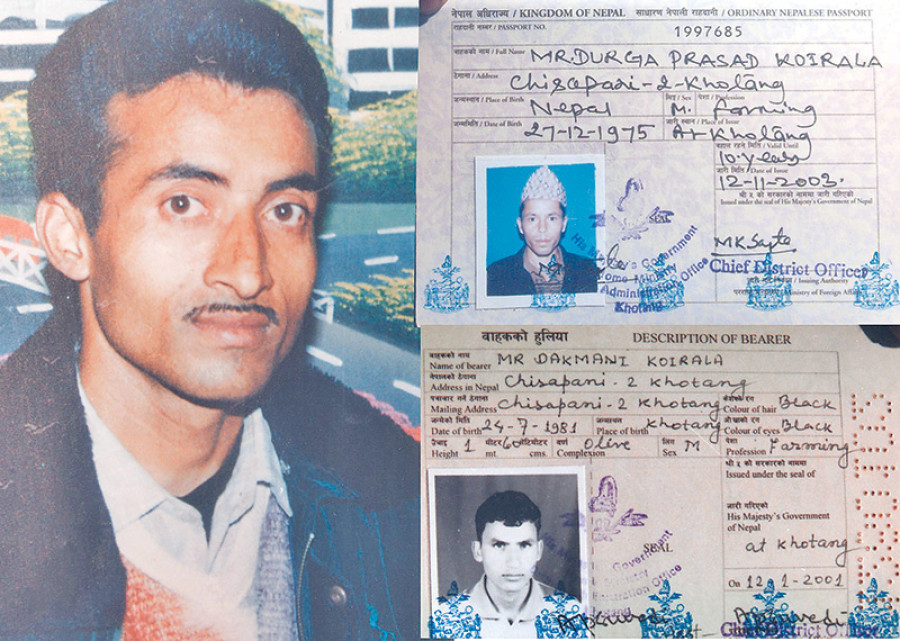

As for what had happened, according to witnesses, on the 6th of December, Bhattarai was hosting a cousin, Dak Mani Koirala, and Durga Prasad Koirala, who were planning to leave Nepal for foreign employment. The Koiralas had their passports ready and were looking around for money to finance their trip. Getting word from Bhattarai to go over to his house across the valley, they had left home in the afternoon with the intention of staying the night there. Everyone was in by 10 in the evening, but suddenly roused by loud kicks on the doors at around 1 am. When the Koiralas called out from inside that they were only guests, those outside responded that they were looking for precisely such guests, a reference to Maoists who would seek shelter with locals. Thereafter, followed a nightmare of aggressive interrogation and about an hour later all three were taken away towards the river valley. Bhattarai’s family heard three gunshots a little while later. In the morning the bodies of all three were found by the riverside.

All those who showed up that night were wearing Nepal Army uniforms, except for one individual who was in mufti and had his face covered, and thus who could not be recognised in the dim light. The money that the Koiralas had was missing and, as the family later found out, so were papers related to Bhattarai’s financial dealings from his safebox which the soldiers had ordered to be opened. Even at that time it was suspected that the person responsible for this senseless killing could be one of Bhattarai’s own relatives, one with whom a deal had gone sour, but who was a low-ranking officer in the army. The army later tried and convicted that individual and gave him a two-year sentence. Two years, for the cold-blooded murder of three innocents. Twenty-three-year-old Dak Mani left behind a pregnant wife and his dreams of making it big as a migrant worker.

Living with murderers

We later learnt the place had suffered another tragedy as well. Earlier, in September of that same year, an army patrol had randomly rounded up young men as they made their way to the small bazaar of Chisapani, asking questions and beating them at will. Five were later taken away by the soldiers and their families heard on the radio that same evening that four Maoists had been killed in a firefight in the jungles around Chiasapani. The next morning one of the five was let go with a warning, but the rest, Dev Bahadur Rai (30), Kailash Karki (20), Thir Bahadur Karki (17) and Deepak Bista (16), were shot and buried by the river not far from Chisapani.

No one has ever been brought to account for the killings of this Chisapani quartet. In fact, most people do not even know about this incident. Imagine the national radio announcing their deaths a day before they were actually killed. It is true. I could not go back to the radio transmission but I did check the government mouthpiece, Gorkhapatra, which duly published everything put out by government sources, and it is there, the deaths announced even as the four lay in army captivity.

Such are the deep wounds of war, and it will take many more cases like Dhungel’s to be brought to justice before some kind of normalcy will return to the lives of those affected such as Deepak Bista’s family in Chisapani, Khotang. Only then might they be able to learn to live alongside murderers and torturers.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu