Opinion

Exercise in futility

Accusing the government of being inept without understanding the ground realities will not help anyone

Nirnaya Bhatta

It is not surprising to be aggravated by the pervasive rhetoric that the government is completely inept. Given the difficulties that lie ahead in the immediate future—incessant tremors, a heavy monsoon, a seemingly dysfunctional civil society, and a desperate state—merely criticising the government at this juncture is a for further adversity.

Constructive criticism would entail knowing exactly where the government has gone wrong and how it can be corrected. But the baseless accusations that are currently being made are disingenuous, as they don’t seem to understand how the government functions and the factors that determine its structural capacity to act.

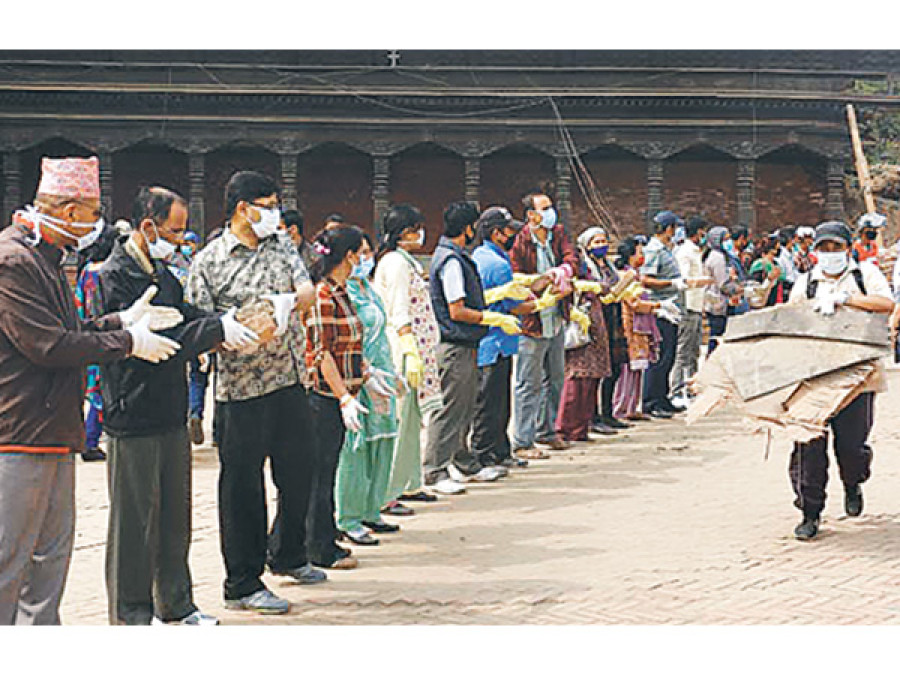

“A fundamental dilemma in disaster response is the tension between the natural impulse to respond quickly and doing things right,” writes Elizabeth Ferris in a Brookings paper explaining what went wrong in Haiti. Certainly, the ad hoc relief efforts carried out by innumerable volunteers and non-government entities are commendable and seem to demonstrate that ‘natural impulse to respond quickly’. But once the dust settles, it is plausible to assume that the volume of volunteers will plunge, as those unaffected will resume their normal lives, or to put it bluntly, they will move on. Then, who will be left to help those who need continued long-term assistance? Here, ‘doing things right’ will entail engaging local communities themselves in the rebuilding process and more crucially, ensuring that government measures benefit the affected.

Dangers of a tar brush

The dangers of continually putting aspersions on the government will inevitably act as a double-edged sword. While weakening the existing mechanism place to cope with the emergency at hand, it will also discourage individuals in the government from putting in their best efforts, even when some of them have no doubt undergone personal tragedies themselves. There have been countless reports of Army personnel continuing with rescue and relief even as they too lost family and homes.

The very nature of government is its visibility, both at home and globally. Hence, it is possible to hold them accountable. In democracies, the legitimacy of any government is derived from the people. When these very people recurrently demonstrate dismay at the government, along with the loss of its authority, it also loses the capacity to act. Once the buck finishes being passed over, having moved through all avenues, it inevitably ends up in the hands of the government.

Even though the Haitian government was weak before the earthquake struck in 2010, it lost even its due legitimacy with the incessant criticisms against it, both from Haitians, as well as international communities. This can even lead to a tearing of the social fabric. We should be really careful what we wish for at this juncture and in this matter, because the consequent results could lead to uncalled-for complications. An abrupt breakdown of the state is the last thing we need now.

The government’s role in the rebuilding phase will be most integral, as other entities neither have the manpower nor the resources to carry out work on a large scale. Existing government mechanisms, such as the National Emergency Operation Centre (NEOC) and the extended District Emergency Operation Centres (DEOC), will have to coordinate and work in tandem with the centre in this regard. Considering the government’s pervasive reach across the country, they are best ‘stocked’ to deal with the situation at hand, especially in terms of rebuilding the dilapidated districts. Furthermore, when the international actors leave, it will automatically fall to the government to oversee and ensure that the lives of badly affected are brought to a state of normalcy.

Let us take off our myopic glasses and look at the government from a distance—as a massive organisation made up of fellow Nepalis. They are just not used to being assisted by ‘outsiders’. Capacitating government individuals is a prime task at the moment, which probably is not even plausible given their immediate engagements. But we are not be in a position to play the ‘us and them’ game at this moment. It is all of ‘us’ who are hurt.

What is to be done

Let’s be clear about the scale of the problem we are faced with at the moment. Eight million people have been affected, with 1.4 million people in need of food aid immediately, according to the UN. The country as a whole has probably never faced problem of this magnitude before.

The willingness of many organisations to help needs to be complimented by rigorous planning and strategic thinking from the centre. The immediate need is to ‘dress the wounds’ of the aggrieved and in the longer term, to rebuild Nepal as a resilient society. To accomplish the latter, we need to channel the good intents and competence of millions of Nepalis—civilians, the government, and the international community. There is a dire need for the international community to trust the government, and vice-versa. While the latter understand the ground realities well, the former is equipped with technical expertise and resources. But the tricky question is, who will take the lead in all of this? Can we envision an entity that can accommodate all these parties? A great many eyebrows were raised when the government announced that the Prime Minister’s Disaster Relief Fund would regulate all incoming aid money.

There might not be a better time than this, given the urgency of the situation, to introduce a new mechanism that will compel the state apparatus to be transparent and accountable. If the government wants to be trusted, it needs to demonstrate to the public that it is ready to be transparent. Civil society too needs a new role. This is not a time for accusations, but for constructive criticism.

Now, the public has more access to social media and it is continually projecting the government as the ‘bad guy’ without proper evaluation. But one thing is for sure, if Nepal’s government is already declared to have failed, it will be of no utility to anyone whatsoever.

Bhatta is a researcher at the Leadership Lab at Daayitwa Abhiyaan, an NGO

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu