Opinion

A federal seat

In the churning over federalism, discussions over a federal capital have been resigned to the sidelines

Semanta Dahal

Debate deferred

On a positive note however, developments thus far show that parties have been able to inch closer to a deal on federalism. With the protracted constitution-making process sufficiently wearing down, the traditionally federalism-phobic Nepali Congress (NC) and CPN-UML have finally accepted attributing ethnicity as a defining criterion for identity. In the case of the UCPN (Maoist) and the Madhes-based parties, they have albeit reluctantly abandoned the unworkable concept of priority rights (agra adhikar) in ethnically carved-out provinces. As reported and mentioned in a speech delivered by Chair of the Political Dialogue and Consensus Committee (PDCC) Baburam Bhattarai in the CA, the January 22 deadline was missed because of a failure to reach compromise on Tarai districts lying on the other sides of the Koshi and Karnali River. Since all sides were agreeable to a accord on ethnic criteria, the dispute stemming from Sunsari, Morang, Jhapa, Kailali, and Kanchanpur is not because of ‘identity’ not being accepted for Nepal’s federalisation. This is a larger issue of gerrymandering and a contest not to lose the right to control the water discharge at Chatara and Chisapani.

But amidst this conundrum and amidst this enterprise to engineer a solution to Nepal’s problem of ethnic disenchantment, one crucial issue, which is core to the federalism debate, has been resigned to the sidelines—the setting up of a federal capital. From James Madison’s argument during the framing of the US constitution implying the need of a federal government to have complete authority at its seat of government to the delayed creation of Brussels as federated entity and also the capital city of Belgium (it took nine years), federal capitals have a chequered past.

Models from elsewhere

“Capital cities,” Canadian political scientist John Meisel has remarked, “are immensely subtle and complicated things”. This is even truer when it comes to the capital of a federal country. In a remarkably burdensome role, federal capitals, unlike capitals of countries modelled on a unitary system, have to mete out certain designs and objectives that achieve an adequate balance that forecloses the federal capital from appearing to favour one particular constituents unit (states/provinces) and at the same time, allow the local citizenry of the capital to govern themselves by preventing governance from being usurped by the national (federal) government. The role that needs to be played by the federal capital is described by David Rowat as an alignment to mitigate the conflict between ‘federal/national interests’ and ‘local interests’. Besides this alignment, another attribute of a federal capital should be to reflect diversity and symbolise the whole nation. Hence, this two-part essay attempts to set the stage for discussions for an appropriate model for a capital of soon-to-become federal Nepal.

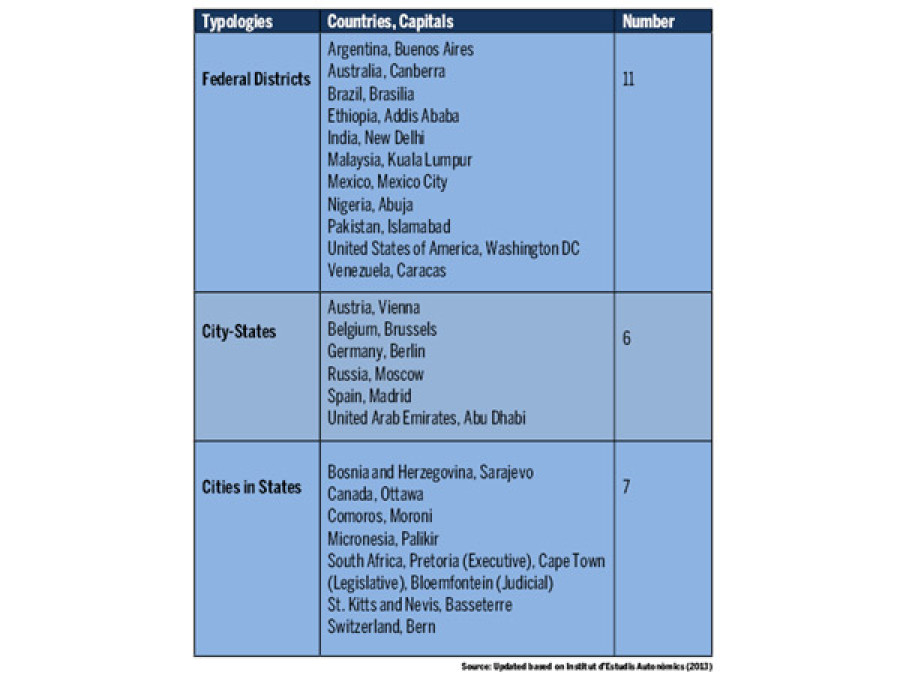

From the survey of 24 countries that are officially identified as federal or have completed the transition to federalism, it seems three categories of design of governance structures for federal capitals are being experimented with. Slack and Chattopadhyay classify them as: federal districts; capitals in constituent units (cities in a state); and city states (constituents units as capitals).

The classical model of governance for a federal capital by creating a separate federal district (also called federal/union territories) has its genesis in Madison’s argument to avoid the dominance of any single state or province over the seat of the federal government. This is the reason the US capital was relocated in 1790 from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia, a territory carved out from the states of Maryland and Virginia. Capitals falling under this group are the largest in number and can arguably achieve two interlaced objectives. First, they maintain an arms-length relationship with other states/provinces and second, they have supervening administrative authority over decision making on public safety, land use, and public finance in the federal capital.

Even though federal districts are ostensibly the most popular governance structure for federal capitals, European federal countries have particularly not trodden down the same path. In evolving their own sui generis model, European nations have created federal capitals with status as both federated constituent unit (states/provinces) and capitals of the federation. Such city-states are usually placed in symmetry with other constituent units of the federation, with the federal government not vested with any special authority over the governance of the federal capital. All federal capitals grouped in this category are politically, culturally, and economically important large cities. Amongst these examples, Brussels is exemplary because of the peculiar way in which it has managed the aspirations of multilingual Belgium.

The third category of federal capitals is cities within the constituent units of federation. Examples in this group are not monolithic either. This group is represented by island nations (Comoros, Micronesia, and St. Kitts and Nevis), a small landlocked nation with a large number of units (Switzerland), a nation under perpetual ethnic tensions (Bosnia and Herzegovina), a large bilingual country (Canada), and a country with three capitals for three branches of the state (South Africa). In this ‘cities within states’ model, the provincial government strips the authority of the federal government with the latter having no or minimum rights of control over the federal capital.

All these three models have some limitations when it comes to making a choice for devising a capital for a multiethnic country. How truly can a federal district reflect the nation’s diversity? Will the concerned city state in a member-state model be trusted by other constituent units to act neutrally? Can cities within the state model take genuine input and control that the federal government of the nation deserves? These and other related questions arise. But whether the reports prepared on federalism by State Restructuring Committee of the first CA, the High-Level State Restructuring Commission, or the NC-UML proposal submitted to the PDCC have tackled this issue or not will be taken up in the next piece.

Dahal is an advocate. This is the first of a two-part article

13.58°C Kathmandu

13.58°C Kathmandu