National

Conflict victims losing patience—and lives—in wait for justice

In 15 years since the peace accord was signed, political parties have failed even to assure insurgency victims that they’ll be delivered due justice.

Binod Ghimire

The Maoist insurgency was at its peak in 2004. Anyone who didn’t agree with the ideology of the CPN (Maoist) in the area of their influence was subjected to severe punishments, even death. Ghanshyam Sapkota from Khagendrapur, Kapilvastu was one of them.

In November 2004, a group of Maoist combatants seized him and gave severe thrashing accusing him of spying on them. They hammered both his legs, permanently disabling him. He could never stand again.

“The Maoists ruined our lives,” Sapkota’s wife Sabitri told the Post over the phone from Kapilvastu. “They rose to power because of the sacrifices of people like us and now we are being denied justice.”

Following the Comprehensive Peace Accord in 2006, the conflict victims launched a campaign seeking justice from the Maoists, who had joined mainstream politics. Sapkota was one of the campaigners. He played a key role in organising the conflict victims from his district to make their voice louder.

Despite his disability, Sapkota continuously campaigned for the cause, hoping that he and many other victims like him would get justice one day. Justice was denied for so long that he lost his life before he got it. He died of illness on May 1 at the age of 61.

“The insensitive governments and the commissions didn’t hear his cry for justice,” said Sabitri, on the eve of the 15th anniversary of the peace accord. “He lived a hard life after the incident and couldn’t even die peacefully.”

Providing justice for the victims of the decade-long insurgency was one of the major promises of the peace deal signed on November 21, 2006. As per the accord, both the state and the Maoists were required to reveal within 60 days the names of the people who were forcibly disappeared or killed during the conflict. Both the government and the Maoist party had agreed to form transitional justice mechanisms to investigate the cases of human rights violations and crime against humanity and deliver justice to the victims.

However, 15 years after the agreement, the victims and their families are still awaiting justice. The wait is so long that many of those fighting for justice are unlikely to get it in their lifetime—like Sapkota.

A Tharu family in Bardiya is another example in the episode.

On June 2, 2002, an army squad was chasing Maoist combatants in Bhurigaun, Bardiya when they passed by the house of Purna Bahadur Chaudhary. Suspecting that the combatants had entered Chaudhary’s house, the army opened fire indiscriminately, killing Chaudhary’s 19-year-old son Bhauna. Bhauna was having lunch when the army killed him.

As the situation was not favourable then to raise the issue of justice, Chaudhary started his fight for justice for his son only after the peace deal was signed. His campaigning was not limited to Bardiya; he was in Kathmandu every time the conflict victims organised programmes to pressure the government.

Chaudhary was diagnosed with cancer a few years back, which took his life in August 2019.

“My father said he would die only after the culprits who killed my brother were brought to book,” Kaluram, younger brother to Bhauna, told the Post. “That couldn’t happen because those in power never cared about the conflict victims and their families.”

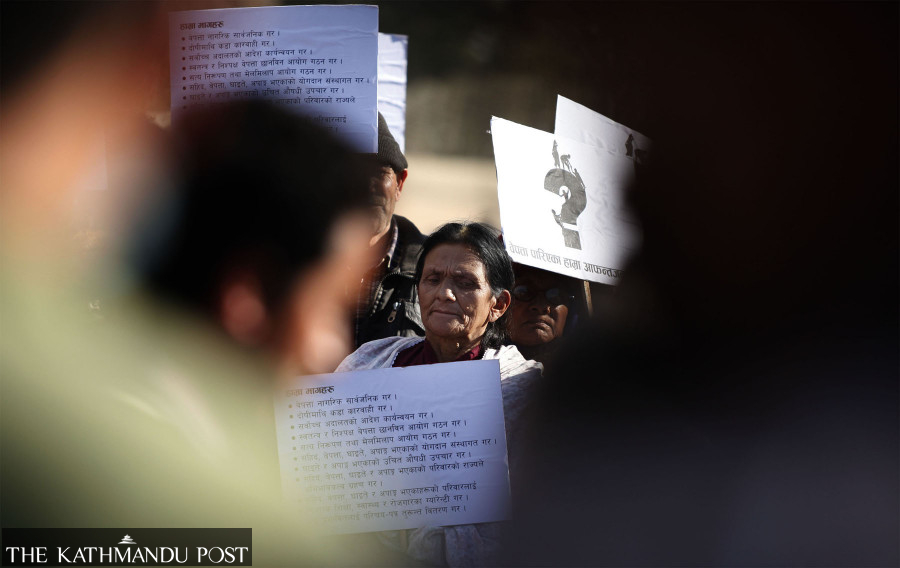

Campaigners say dozens of conflict victims and their relatives who were fighting for justice have lost their lives in the wait.

“Neither the government nor the transitional justice commissions are concerned about the victims,” Suman Adhikari, founding chairperson of the Conflict Victims Common Platform, told the Post. “Their strategy is to tire and silence the victims and they are succeeding in their mission. Delayed justice means more people campaigning for justice could die in the days to come.”

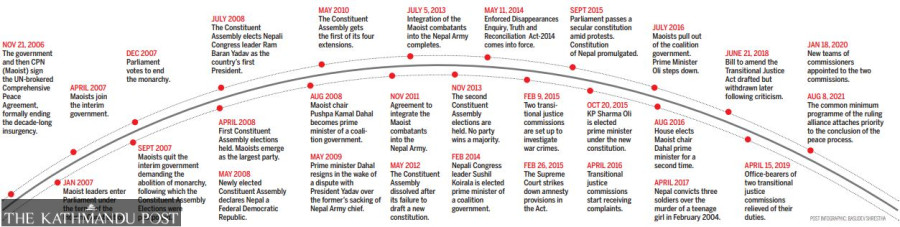

He says every government and politicians and those heading the commissions say they are positive and committed to wrapping up the peace process by concluding the transitional justice process, but in reality they are acting just the opposite. The ruling alliance on August 8 unveiled its common minimum programme attaching priority to transitional justice.

The document meant to guide the functioning of the Sher Bahadur Deuba government vows to implement the Comprehensive Peace Accord and to amend the Enforced Disappeared Enquiry and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act. It also talks about equipping the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with adequate funds and resources.

However, neither has there been any progress in amending the Act nor has the government been willing to provide the resources to the commissions. Even the drafters of the common minimum programme agree there hasn’t been much progress towards this end. The ruling alliance is rather busy blaming the main opposition CPN-UML for the lack of progress.

“Every decision on the transitional justice process has to be made in consensus among the parties. However, the UML is not willing for it,” Dev Gurung, chief whip of the CPN (Maoist Centre), who was involved in preparing the common minimum programme, told the Post.

Although Gurung blamed the UML for not facilitating the Act’s revision, the government, in which his party is a key partner, is also reluctant to provide resources to both the commissions. The truth commission is supposed to have 90 officials, but it currently has just 50 and half of them are office assistants and drivers. The commission has a sheer deficit of legal and technical staff who can hear victims’ cases.

The provincial offices of the commissions are closed now because the government hasn’t allocated funds for their operation. The same applies to the disappearance commission, which is supposed to have 70 officials but there are just 40.

“We were planning to expand offices beyond provinces to expedite the investigations process but we have been forced to close our existing offices,” Ganesh Datta Bhatta, chairperson of the truth commission, told the Post. “Our performance has been marred in lack of resources.”

Those who have a close understanding of the ongoing process, however, say lack of resources alone is not the reason for the delays. They blame the unwillingness of the political parties to be the main reason. Former chief justice Kalyan Shrestha says the parties under pressure from national and international circles constituted the commissions just to show the world that they are working on it.

“If only the parties were a little bothered about providing justice, they wouldn’t have waited so long just to amend the Act,” he told the Post. “I don’t see the transitional justice process making any headway anytime soon.”

Shrestha’s bench in February 2015 struck down amnesty provisions in the Act and directed the government to amend it with immediate effect. Instead of abiding by the verdict then, the government moved the court demanding a review, which the court rejected. The rejection left the government with no option but to abide by the verdict. However, despite several commitments, the Act remains unamended.

Shrestha says the commissions that are led by those picked by the political parties neither have the legitimacy nor the expertise to investigate the complaints and deliver justice. The truth commission has received 63,718 complaints. In the last seven years, the commission has completed preliminary investigation into around 3,800 complaints while putting aside an additional 3,000 cases as not qualifying to be complaints.

Currently, the commission is issuing identity cards to the victims and recommending reparation in some cases.

The disappearance commission, on other hand, had received 3,223 complaints. It is investigating only 2,506 of them saying that the rest do not fall under its jurisdiction. The commission is yet to complete a preliminary investigation of all the complaints.

The commission had claimed that it would, from November, start exhuming the bodies of those who were killed allegedly after forced disappearances. It now says it doesn’t have experts for digging up the bodies.

Bhatta, the chairperson of the truth commission, agrees that there have been delays. “It is a matter of shame that the victims haven’t got justice in the last 15 years. I admit the delay,” he told the Post. “However, we can deliver justice only when there is cooperation from every sector and when the government provides needed support.”

He claimed that the truth commission can investigate all the cases in the next four years if the government provides the budget to set up 18 offices including in the places where the high courts are located and the stakeholders cooperated. He said the commission has already completed its investigation into around 35 complaints and recommended compensation and reparation for them.

At least 13,000 people lost their lives while 1,333 people disappeared during the insurgency that lasted from 1996 to 2006.

Human rights activists, however, say there could be a question of legitimacy of the investigation as victims’ groups and national and international human rights organisations have raised serious questions over their very formation. “The victims are still demanding reappointment of office-bearers to the commissions in a transparent manner. International human rights organisations too had expressed their reservations over the appointments,” Kapil Shrestha, a former member of the National Human Rights Commission, told the Post. “The process that is not owned by stakeholders is meaningless.”

The erstwhile government relieved the chairpersons and members of both the commissions from their positions on April 15, 2019 on the charge of non-performance. Formed in February, 2015, the commissions hadn’t done anything significant other than collecting the complaints.

The incumbent chairpersons and members were picked in January last year based on their political affiliations. The victims’ groups have been reiterating that the government should appoint a new team through a transparent process. International human rights organisations have been expressing similar concerns.

On Saturday, four international human rights organisations said the existing commissions lack the trust of victims. Issuing a statement, the Amnesty International, the International Commission of Jurists, the Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International called on the Nepal government to put the needs of victims front and centre and set out a clear timeline for holding meaningful consultations and upholding its legal obligations so as to enable a credible transitional justice process.

Experts on transitional justice say that by delaying justice, the government and political parties are inviting another conflict. “The government and the parties must be aware of this fact before it is too late,” said Shrestha, the former chief justice.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu