National

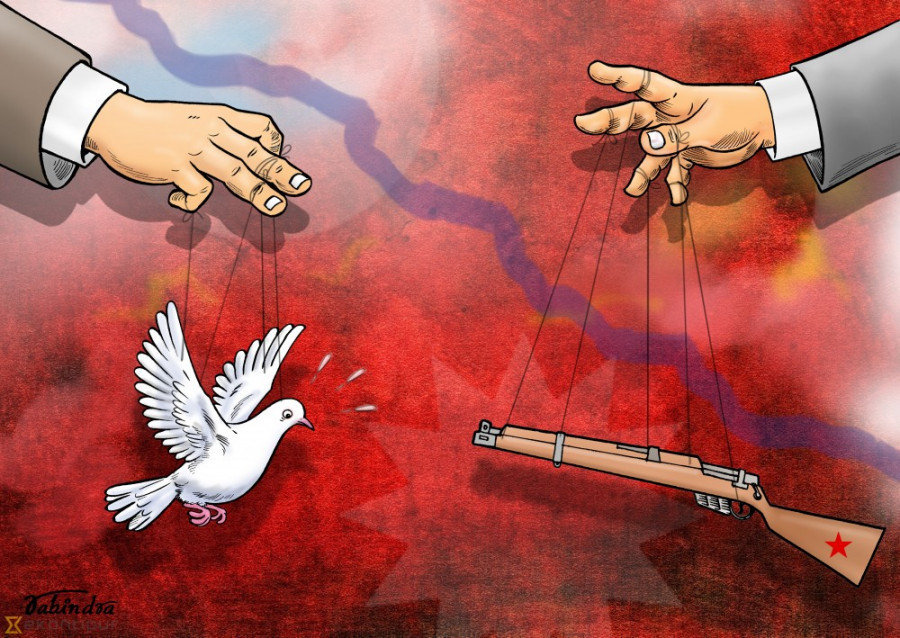

Nepal yet to ensure transitional justice

Officials have been repeating same commitments at international fora, but have done little to implement them.

Binod Ghimire

In his address to the Universal Periodic Review session on Thursday Minister for Foreign Affairs Pradeep Gyawali reiterated that Nepal was committed to concluding the transitional justice process ensuring justice to all victims of human rights violation during the decade-long Maoist insurgency.

He claimed that the transitional justice process is guided by the Comprehensive Peace Accord, various directives from the Supreme Court and relevant international commitments, concerns of the victims and the country’s ground realities. This was the third time Gyawali made the commitment in front of the United Nations’ forum in the last two years.

In March 2019 addressing the 40th session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, Gyawali had said the government was preparing to amend prevailing laws related to transitional justice in consultation with, and participation of, the victims. A year later, in February 2020, speaking at the 43rd session of the council he said the transitional justice process will be concluded by taking the victims into confidence.

Despite the reiterated claim, the government hasn’t taken concrete steps towards bringing the victims of the conflict on board and revising the Enforced Disappeared Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act, 2014. “I don’t think the international community even believes in Nepal’s commitments anymore,” Kapil Shrestha, a former member of the National Human Rights Commission, told the Post. “Our government has made a mockery of itself at an international forum.”

In October, Nepal was re-elected as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council. It was first elected to the position for two years in January 2018 with a role to ensure that international human rights standards are implemented in UN member countries. In the opinion of Shrestha, who has been a rights activist for years, a country such as Nepal with a deplorable human rights record doesn’t have the moral ground to press other countries to abide by human rights principles.

“Democratic values and a good human rights record had been Nepal’s strength in the past,” said Shrestha. “However, the image has been tarnished over the years.” Fourteen years have passed since the Comprehensive Peace Accord was signed. But thousands of victims from the armed conflict are still struggling for justice. The tenure of the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission expires on February 9. Although the government has made up the mind to extend their term, it is still clueless about revising the law as directed by the Supreme Court.

A few months after the law was enacted in 2015, the Supreme Court, ruling on a writ petition, had directed the government to amend the law saying that perpetrators of gross human rights violations such as enforced disappearance, rape, torture and extrajudicial killing can’t be pardoned.

“The terms of both the commissions will be extended,” Lila Nath Shrestha, minister for Law and Justice, told the Post. “The government, however, has not decided about the revision in the law.” He said the government is preparing to hold interactions with major political parties in an attempt to forge consensus on the amendment.

The Nepal Communist Party and the Nepali Congress had held rounds of discussions to forge consensus on the amendment to the Act. However, the intense feud within the Nepal Communist Party overshadowed the issue. Nepali Congress leader Ramesh Lekhak, assigned by the party to negotiate with other stakeholders on transitional justice issues, said it’s been months since the government last held discussions on the matter.

“I don’t think it’s even on the mind of the government,” he told the Post. “The deepening political crisis has left the issue neglected.”

Those closely following the transitional justice process say all major parties are equally responsible for the little progress made in delivering justice to conflict victims. Gauri Pradhan, former member of the National Human Rights Commission, said that major political parties believe that by delaying the delivery of justice, they can run away from their responsibility. “The ongoing transitional justice process can’t deliver justice,” he told the Post. “The parties’ failure to abide by their commitments is eroding the international community’s trust in the government.”

He said the government, in consultation with the major parties and the victims of the conflict, should immediately revise the Act so that it can generate hope among the victims and the international community.

However, the Law Ministry doesn’t have immediate plans to consult the victims nor has it reached out to them recently. “I think the government has forgotten our existence,” Gopal Shah, chairperson of Conflict Victims’ National Network, told the Post. “It seems the parties have made up their mind that they will continue to dally over the delivery of justice.”

20.9°C Kathmandu

20.9°C Kathmandu