National

Lost and never found: Hundreds of children, more girls than boys, go missing every year not to be found

The majority of the children that go missing are eventually found but stakeholders fear all those who go missing are vulnerable to trafficking and exploitation.

Chandan Kumar Mandal

Last week, the border city of Birgunj was rocked after two children went missing. The two sixth graders did not return home after their tutorial classes on Saturday morning.

“At first we thought that he must have stayed out playing cricket as it was Saturday,” father of one of the children told the Post, requesting anonymity.

Family members, neighbours and the local police looked everywhere for them but there was no sign of the children anywhere.

Apparently, both children had crossed the border and reached the Indian city of Patna—more than 200km away.

“They crossed the border, took a bus and reached Patna after midnight. They slept in the bus,” said the father. “After roaming around near the bus park on Sunday morning, they got scared and approached a nearby police station seeking help. The police then called his mum.”

Family members, along with Nepal Police personnel, rushed to bring back the children. Both of them made it home on Monday.

“We had given up our hope that we would get our kids back,” said the father. “People were telling us that our kids might have been kidnapped. Anything could happen to them. We are middle-class families and worried how we could have even managed if there had been demands for ransom.”

Not every family is as fortunate as these two from Birgunj.

A 16-year-old boy, originally from Mahottari, has gone missing from Duwakot, Bhaktapur, for more than a month now. According to S., the missing boy’s uncle who did not want his identity to be disclosed, they have no information of his whereabouts.

“He has been missing since the afternoon of December 8,” said S. “We have filed a missing person report with the police, inspected CCTV footage and called our relatives and friends. However, we have not heard any news about him. The family is going through tremendous emotional stress.”

Every year, thousands of children go missing from different parts of the country. However, hundreds never return home, leaving their families in pain and suffering worrying about their safety.

Every month around 200 to 300 children, or up to ten every day, go missing, according to government data.

The population below the age of 18 years is defined as children as per the Children's Act, 2018.

“Children go missing when they are separated from their parents or when they forget directions home at a new place. Some even run away from home. These are the usual reasons behind missing cases,” said Ram Bahadur Chand, information officer with the National Child Rights Council. “Some are believed to have been even kidnapped or trafficked. However, the reason behind their missing can only be determined when they come in contact with families.”

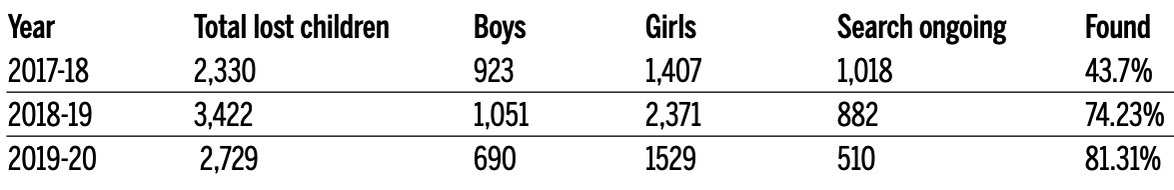

According to the council, in the fiscal year 2017-18, a total of 2,330 children—923 boys and 1,407 girls—went missing from different parts of the country. In 2018-19, the number stood at 3,422, with 1,051 boys and 2,371 girls.

Last fiscal year 2,729 children went missing, shows the latest ‘State of Children in Nepal 2020’ report.

According to Rudra Kumar Giri, police inspector at the National Centre for Children at Risk, hardly any day goes by without the centre receiving reports of missing children.

“Reports of at least four to five children of all age groups missing are filed every day. The number of children going missing also sees a surge during festival season or when families go shopping,” Giri told the Post.

“If the children are missing from Kathmandu Valley, then we immediately start a search operation with the help of the area police, and if it is a matter from outside the Valley, then we relay the information to the district police.”

The National Child Rights Council and Nepal Police jointly operate National Centre for Children at Risk (hotline number 104) from Bhrikuti Mandap in Kathmandu. There is also a Child Helpline (toll-free 1098) for supporting targeted or vulnerable children.

The council also provides service related to search for lost children, family tracing of destitute and infirm children found in the streets, family reunification, and community reintegration in 74 districts. Outside the Kathmandu valley, these services are integrated with the Women, Children and Senior Citizens Service Centers of Nepal Police.

“While these numbers show an alarming picture, we should also note that some cases of children missing are not even reported,” said Benu Maya Gurung, executive director with the Alliance Against Trafficking in Women and Children in Nepal (AATWIN), a national level network of non-governmental organisations.

But most of the children reported missing are found. Of the 2,330 children that went missing in 2017-18, 1,312 were later found. Among the 3,422 reported missing in 2018-19, 2540 were found and in the fiscal year 2019-20 of the 2,729 reported missing, 2,219 were found.

Although the proportion of missing children has been higher in the last two fiscal years, that was not always the case.

“One year the success rate remained at around 26 percent. Then for a few years, the proportion of missing children found was at around 60 percent,” said Chand. “In 2018-19, it was around 74 percent and last year it was 81 percent. The success rate has improved but there are children who still remain missing.”

Government officials, however, say the actual number of children still missing may be lower than what records show as families file missing person reports as soon their children are lost, but don’t always report back to the authorities when they are found.

“Also, sometimes information like addresses and contact details are recorded wrong and this could be a mistake of the staff or the person filing the report,” said Chand. “We cannot reach out to them later.”

According to experts in the field, children, who are already at the risk of human trafficking, forced labour and other abuses, become even more vulnerable when they go missing.

The National Report on Trafficking in Person estimated that nearly 5,000 children were trafficked in the year 2018-19.

“Missing children are highly vulnerable as they are likely to trafficked for the sex trade and forced labour,” said Gurung. “Some could have already been trafficked and therefore missing whereas others are missing but remain at the high risk of trafficking in future.”

The National Human Rights Commission in 2019 said nearly 1.5 million Nepalis are at risk of various forms of human trafficking. Most vulnerable among these are aspiring migrant workers, Nepalis working abroad, people in the adult entertainment sector, girls and women from rural areas, missing persons and child labourers.

According to Gurung, there is a strong link between missing children and their chance of being trafficking.

“Not all of those still missing are trafficked. But they are more likely to be trafficked or at a higher risk of trafficking,” said Gurung. “Children are lured before they go missing. Sometimes they go missing before they are trafficked or some may have already been trafficked when they are reported missing. Likewise, some might have fled their homes and are likely to be trafficked later. It’s always easy to steal or traffic children who are left unattended.”

The majority of children missing are girls and hence more likely to be trafficked.

Last fiscal year, a whopping 1,898 girls were reported missing out of the total 2,729 missing children. In 2018-19, as many as 2,371 among the 3,422 children missing were girls.

Of those still missing from 2018-19, 655 are girls and 226 boys while from 2019-20, 369 are girls and 141 boys.

Chand, Giri and Gurung agree there is a connection between missing children and the probability of them being trafficked.

“There are instances of missing children being rescued from sexual exploitation or exploitative labour conditions. Even during our consultations with entertainment sector workers, they have shared how they had run away from home and landed up in that sector,” said Gurung. “We hardly see girls among street children which could also mean they might have already been trafficked or ended up in the entertainment sector.”

Officials claim that they are taking steps to mitigate the risk of children going missing and are raising awareness among children at schools.

“The government has been constantly monitoring and rescuing children who could be at risk,” said Chand. “Besides call centres, we are making children aware at schools of 104 so that they can call for help whenever they are in trouble.”

However, experts like Gurung believe that whatever is being told to school-going children in schools is not enough for safeguarding those children at the risk of exploitation.

“There are basic concepts in the curriculum like human trafficking at secondary level. Such information should start at an early age as chances of children dropping out of school before they get to the secondary levels are higher in rural areas and this means they can never learn about these things,” said Gurung. “What is more important than this theoretical knowledge is making children aware through extracurricular activities. Only literature will not be enough to protect these children.”

In Bhaktapur and Mahottari, parents and other family members of the 16-year child are still waiting for him. All they have got so far are some fake calls from unidentified people asking for ransom.

“We have reported the National Centre for Children at Risk as well,” said S., the boy’s uncle. “We can only hope he returns home safe and sound as soon as possible.”

16.32°C Kathmandu

16.32°C Kathmandu