National

The Covid-19 outbreak so far and how Nepal can prepare for the worst

Even though the number of Covid-19 cases in Nepal remains inexplicably stuck at one, doctors and public health experts warn of a potential disaster if measures aren’t taken.

Post Report

As fear grips the world, the number of people in Nepal diagnosed with Covid-19 remains, inexplicably, at one.

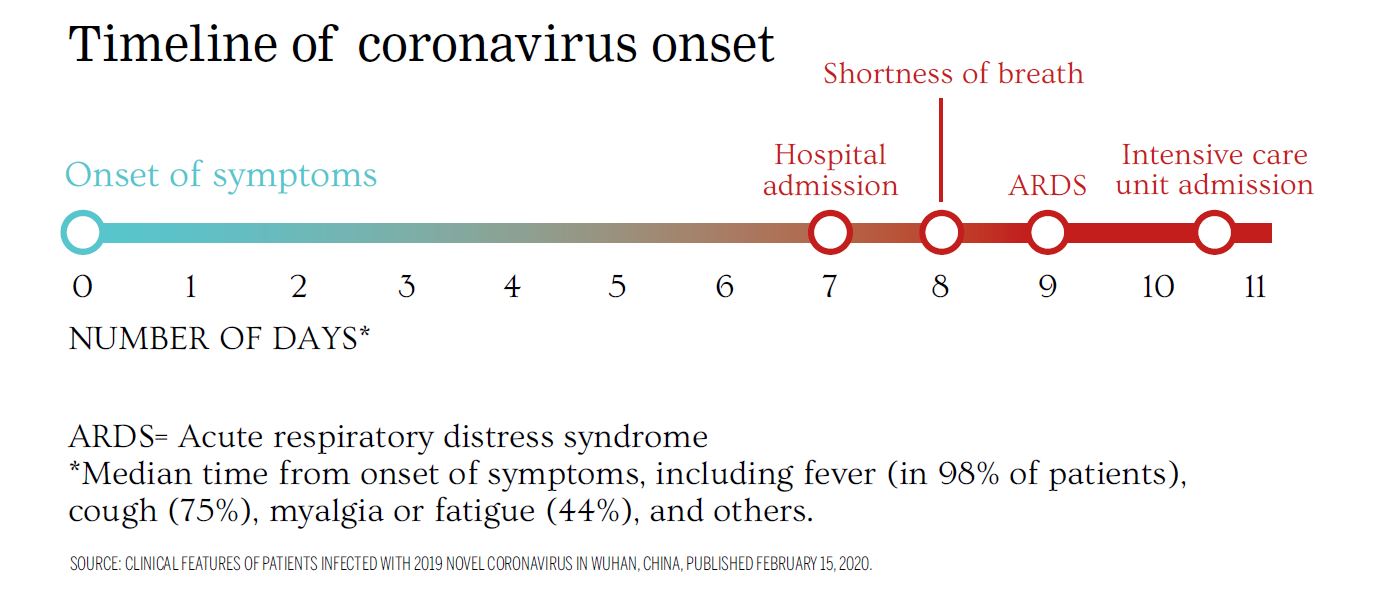

That patient, a 32-year-old student from the Wuhan University of Technology, had admitted himself to the Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital in Teku on January 13 with a cough. He had become ill on January 3, six days before he flew to Nepal. The patient had a mild form of the disease, which had yet to be named at that time, and recovered within 13 days, according to a case study in the Lancet published in February.

The world is on high alert: borders are closing and stringent measures are being taken to limit the spread of Covid-19, as the disease has come to be known. But despite human interventions, the coronavirus, named SARS-nCov-2, has, as of Friday, infected more than 245,000 people and killed more than 10,000 in 160 countries.

But despite the fact that the virus originated in China, and the Nepal government has still not restricted movement from the northern neighbour, Nepal has not yet seen an outbreak. The government has been slow to act, but on Wednesday, it finally decided to restrict all arrivals—even Nepalis—from over 50 countries that have reported outbreaks, from midnight on March 20 to April 15.

On Friday evening, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli announced more measures—halting all flights from March 22 to 31, closing down all non-essential services from March 22 to April 3, and banning all long-haul travel from March 23.

With cases rising in South Asia—and neighbouring India, reporting 223 cases, with which Nepal shares an open border—there are worries that it is just a matter of time before the virus makes an appearance. And when that happens, Nepal’s public health system, which has always been understaffed and under-equipped, will strain to contain the disease.

“No one can be assured regarding the government’s preparations,” Dr Baburam Marasini, former chief of the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, told the Post earlier this week. “Even the concerned officials at the Ministry of Health and Population are not convinced about their own preparations to handle a possible outbreak.”

What we know about Covid-19

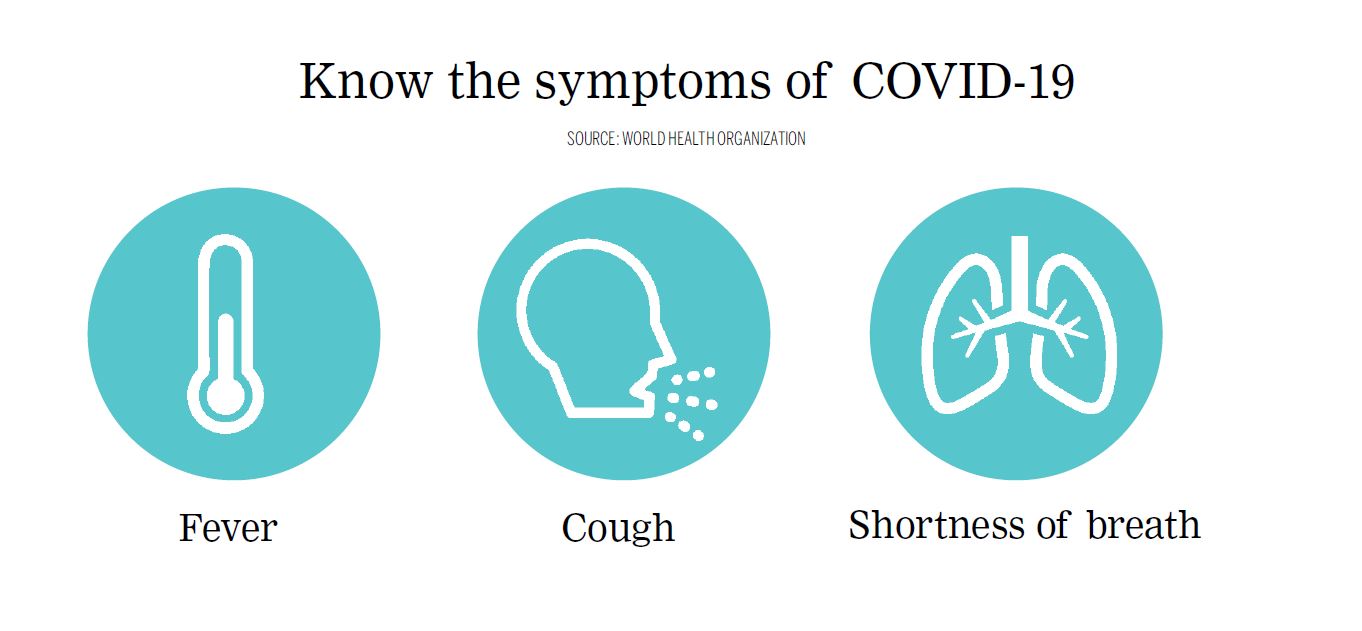

Covid-19 is similar to the flu, causing fever, cough and a sore throat. In both cases, symptoms can vary, from mild to fatal. But Covid-19 is more contagious and the mortality rate is higher.

The first case, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, was seafood trader Wei Guixian, who visited a local health clinic in Wuhan as she was feeling unwell, on December 10. She received medication and returned to work. Eight days later, she was in the hospital and unconscious.

The virus reportedly originated in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, a live animal wet market, although there are conflicting accounts. The coronavirus is a zoonotic disease, meaning it made the jump from animals to humans.

By late December, public health officials in China had already been notified that a new coronavirus was causing illness. Doctors like Ai Fen and Li Wenliang were reprimanded for sharing information about the virus. Dr Li, an ophthalmologist, eventually succumbed to the disease.

The first case outside of China was confirmed in Thailand on January 13. By December 31, there were 27 confirmed cases; six days later, Nepal’s sole case admitted himself to hospital and was confirmed after samples were tested in Hong Kong, on January 24.

By late January, China had leapt into action, albeit belatedly. It placed over 30 million people in Hubei Province under lockdown and swiftly moved to quarantine locals inside their homes. But it was too late.

On January 31, World Health Organization Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced the virus “a public health emergency of international concern.”

The virus spread swiftly. By late February, it had engulfed nations like Iran—over 18,400 cases and over 1,280 deaths—and Italy—over 41,000 cases and over 3,400 deaths.

On March 11, the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic.

“We have never before seen a pandemic sparked by a coronavirus. This is the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus,” said Ghebreyesus ominously. “And we have never before seen a pandemic that can be controlled, at the same time.”

China appears to have managed to get the outbreak under control, reporting no new cases for the first time since the outbreak was identified, on March 19. But outside of China, the virus has only grown. Now, over 170 countries have reported infections and the death toll has been steadily rising.

What is the situation in Nepal

On Wednesday, after weeks of dithering, the High-Level Coordination Committee, led by Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Ishwar Pokhrel took a series of crucial decisions aimed at limiting the spread of Covid-19 to Nepal. All incoming passengers, including Nepalis, from more than 50 countries in Europe, the UK, the Gulf and West Asia, were restricted; the nation-wide Secondary Education Examinations were postponed; all gyms, health clubs, cinema halls and dance bars were asked to close; and all gatherings of more than 25 people were forbidden.

“These strong measures have been taken considering the worldwide impact of the coronavirus, the fear it has created, and recommendations from different quarters,” Yogesh Bhattarai, civil aviation minister, told the Post on Wednesday.

Although these measures were welcome, many public health officials fear that they might not be adequate and the public is not convinced that the government has been doing enough.

On Thursday, a video of Dr Sundar Mani Dixit criticising the government’s response and claiming that the government was not conducting adequate tests since it did not have any testing kits went viral. Although there is a hint of a conspiracy theorist to Dixit, especially his claims that testing kits were being saved for ‘VIPs’, the video struck a chord because most Nepalis do not seem to believe that Nepal, with its dense urban populations, poor safeguards and ailing health infrastructure, could have avoided Covid-19 for so long.

As of March 20, just 546 Nepalis had been tested for Covid-19, with all but one case in January negative, according to the Ministry of Health and Population.

The current testing process consists of assessing whether patients have a fever paired with symptoms of an acute respiratory disease and whether they have preexisting conditions; and then assessing if they have been in contact with someone who may have had Covid-19 within 14 days of presentation, or has been in an affected country. Those arriving in Nepal are checked for fever, and even if they don’t present any symptoms, are asked to self-quarantine themselves. If there is a fever, they are placed in isolation and sent to a designated hospital.

But the airport has long suffered from institutional and infrastructural failures. On March 9, The Diplomat reported that the 13 health workers deployed at Tribhuvan Airport were not adequate to screen passengers coming from China, South Korea, Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia, Japan and Saudi Arabia.

“These health workers aren’t enough for stringent screening of all passengers. Some of the passengers may skip the screening process due to the limited number of health workers,” one passenger told the publication.

On March 18, The Himalayan Times reported that incoming passengers were not being screened properly and that not many were being asked to remain in self-quarantine.

Nepal’s hospitals and laboratories are also woefully under-equipped, first to test potential patients, then to keep them in isolation, and then provide proper care. Officials at the Nepal Public Health Laboratory told the Post that they had only 1,000 testing kits in stock. By March 20, more than half of them have been used, and it is unclear whether the 5,000 kits they had requested from WHO have arrived.

On March 19, the Nepal Medical Council asked all hospitals, both private and public, with over 100 beds to begin operating separate fever clinics and asked everyone to postpone elective surgeries to conserve resources for an outbreak, ensure the protection of health workers, and lessen unnecessary crowds at hospitals and treatment centres.

Besides testing kits, there remains a critical shortage of personal protective gear for frontline health care workers, and a lack of ventilators and ICU beds.

Kathmandu is one of the most densely populated cities in the region and an outbreak here could quickly overwhelm health care facilities. The mortality rate of Covid-19 is not very high—revised to less than 1 percent from an initial estimate of 3.4 percent—but when coronavirus patients flock to hospitals, others who require urgent medical care might not be able to get the care they require.

While young people might be less at risk from the disease—although new evidence is challenging that assumption—they could spread the virus to at-risk populations like the elderly, the infirm and immunocompromised.

What can Nepal do

“To suppress and control epidemics, countries must isolate, test, treat and trace,” Ghebreyesus, the WHO director-general said on March 18, as otherwise “transmission chains can continue at a low level, then resurge once physical distancing measures are lifted.”

From the information from public health experts and the government, Nepal lacks the capacity to do all four—isolate, test, treat and trace.

Each person with Covid-19 transmits coronavirus on average to two to three people. With such a large multiplying factor, there will be exponential growth of cases. If there are 100 cases today, there will be 200 in a couple of days and a thousand in over a week. If contact tracing and isolation measures are not strictly instituted, this number could spiral to a million in a month, which would be disastrous in a country like Nepal.

Doctors have advised contact tracing of all those suspected of having Covid-19, but Nepal’s authorities have failed to account for the one Covid-19 patient’s contacts and his movements. There are frequent reports of people suspected of Covid-19 being allowed to leave hospitals and travel on their own to the Sukraraj Hospital in Teku.

Nepal lacks the technological sophistication that allowed Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea to trace and track their Covid-19 patients using a combination of CCTV surveillance, tracking bracelets, and smartphone apps. But it could mobilise police personnel to track down suspected patients or enforce self-quarantine. CCTV footage could also be employed to trace movements and track down all those who came into contact with a Covid-19 patient.

Although the Nepal Medical Association has asked large hospitals to maintain separate wards for fever patients, proper isolation wards are few and far in between in Kathmandu. The high-level coordination committee, on March 17, decided to establish 120 ICU wards and 1,000-bed isolation wards at seven different hospitals in the Kathmandu Valley. But these are rudimentary at best and not up to quarantine standards. In fact, the Sukraraj Hospital’s quarantine ward, in January, was found to be substandard and lacking in basic facilities like a proper ventilation system by a WHO monitoring team.

So if Nepal remains unable to trace, isolate, and test, will it be able to treat?

“No one believes that a public hospital can be used for the treatment of patients infected with a highly infectious disease like the coronavirus,” Dr Marasini, the former head of the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division flatly told the Post.

Although Covid-19’s symptoms are most often not fatal, the few who will develop serious symptoms, like pneumonia, will require care in the ICU and perhaps even ventilators. Data is sparse on how many ventilators there are in the country, but most doctors believe that they are certain to be inadequate in case of a mass outbreak.

In situations like these, doctors advise clear and frequent communication from the government. Even a single new confirmed case of Covid-19 could send the country into a panic, and the authorities need to make sure that doesn’t happen. A clear, firm single voice that encourages calm would go far towards countering the disinformation that is bound to arise at such times.

The government should also actively be courting support from neighbours and well-wishers, say many doctors and public health experts. China has pledged to send a medical support team and logistics, like it has done in Iran and Italy, and India has set up a $10million fund that any South Asian country can avail of. Numerous non-governmental organisations have also offered help in terms of procurement, logistics and personnel. The government has yet to tap any of these sources of support. By the time the epidemic rears its head in Nepal, it might be too late.

Experts advise governments to send a clear message that self-isolation is key when it comes to the coronavirus. Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli’s address to the nation on Friday evening was a start, but such communication needs to be regular and frequent, advised the Economist earlier this month.

As the virus spreads in close contact, it is also best to enforce social distancing,which is to work in isolation, away from large crowds and public gatherings. As countries across the world go into self-isolation, working from home and avoiding physical interactions in public, Nepal needs to follow suit.

8.84°C Kathmandu

8.84°C Kathmandu