National

Costs shoot up as major projects miss deadlines

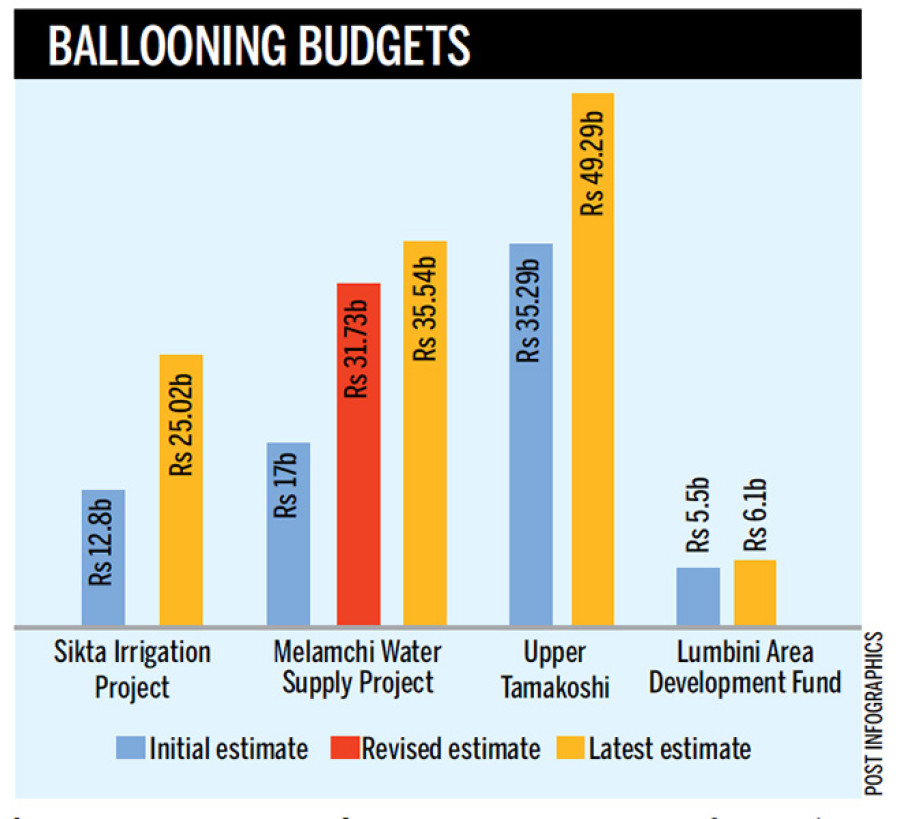

A majority of large infrastructure projects, including many national pride projects, are not only moving at a slow pace but also hurting the state coffers, according to a new report released this week by the National Planning Commission.

Prithvi Man Shrestha

A majority of large infrastructure projects, including many national pride projects, are not only moving at a slow pace but also hurting the state coffers, according to a new report released this week by the National Planning Commission.

Although time and cost overruns are hardly new for government-funded projects, the commission said there was an alarming rise in expenses for some projects.

Take Sikta Irrigation Project for instance. When the project was initiated in 2005-06, it was supposed to be completed by 2014-15 at an estimated cost of Rs12.8 billion. Officials now say the project may not be completed before 2019-20. By the time it is fully operational, the project is expected to cost Rs25.02 billion.

Government officials blame multiple factors for the cost overrun: low bidding by the contractor, collusion between contractors and consultants, and external factors. Infrastructure officials say delayed commencement of projects and the practice of misusing mobilisation advance by contractors also affect the projects.

“Another important factor behind missing deadlines and cost escalation is the failure to ensure perfect project design,” said Tulasi Sitaula, former secretary at the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure. “When the design is changed, it takes more time and the project has to pay the contractor for the variation order. The consultant has to be employed until the work is over.”

Melamchi Water Supply Project is another example of how poorly mega projects are handled in Nepal. Designed to end the perennial water woes of Kathmandu, the first phase of the project is due to be completed by this fiscal year.

As the project went through a series of controversies and delays, its cost has spiralled. When it was started in 2001-02, the initial estimated cost was Rs17 billion. In 2008, the cost was readjusted to Rs31.73 billion before it was increased again to Rs35.54 billion in 2014, according to the commission’s report.

Shankar Sharma, former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission, said the government was equally responsible for the project delays and cost overruns. “The government has a tendency

to instruct the contractor to do the works that are not in the original design,” he said. “This gives the contractor an opportunity to increase the cost.”

The most preferred modus operandi of cost escalation, according to Sharma, is low bidding. Once they win the contract for the lowest bid amount, contractors exploit the legal loopholes to increase costs.

In many projects, the collusion amongst the contractor, project consultant and government officials often leads to increased costs. Project designs are altered in the contractor’s interest while the consultant and government officials also reap benefits.

The use of foreign consultants and construction materials and services is another factor for rising expenses. Projects suffer from ballooning costs due to the depreciation of the Nepali currency against the US dollar. One example of massive cost escalation due to the exchange rate is the Upper Tamakoshi Hydroelectric Project. The 456MW project is one of the few national pride projects with satisfactory progress.

However, the project’s total cost will grow by Rs14 billion when its construction is completed by April 2019. The project also suffered hugely due to the 2015 earthquake and the subsequent Indian blockade, increasing both the deadline and cost for completion.

The project chief, Bigyan Prasad Shrestha, said the project cost shot up by Rs7 billion thanks to the depreciation of the Nepali currency. “We are using around 70 percent foreign goods and services in the project. Thus the exchange rate has a huge role in increasing the project cost,” he said.

Contractors argue that they cannot be blamed solely for the time and cost overruns. “There is a tendency to prepare detailed project reports without proper study. As the design changes frequently, both time and price escalate due to the variation order,” said Bishnu Bhai Shrestha of the Federation of Contractors Association of Nepal.

The government is working on a separate law to govern large infrastructure projects. But Sharma said the move will not address the issue. “We’ve already amended the Public Procurement Act twice,” he said. “It has not helped either.”

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu